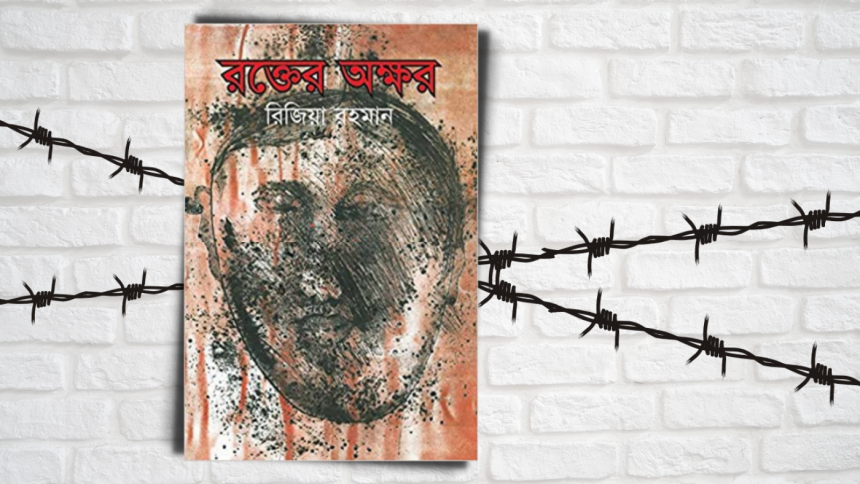

Untold stories of war heroines: Revisiting Rizia Rahman’s ‘Rokter Okshor’

Browsing through the shelves of Baatighar one morning, I came across the Bangla section where my eyes drifted immediately towards a thin book with an off-white and blue cover. I picked it up, read through the blurb and knew I had to take it back home. It was one of the best decisions I've made. Published as early as 1978, Rizia Rahman's well-acclaimed book, Rokter Okshor, narrates the lives of the women who were forced (directly and indirectly) into prostitution in the post-Liberation War era of Bangladesh.

The novel opens in a shabby setting that reflects the reality seen in the brothels of Bangladesh. As goes the saying, "Change is the only constant", so pass the changing days, fates, and lives of the inhabitants of Golapipatti throughout the narrative. A typical morning in such a house carries stories of young girls come to life: Kusum a 14-year-old, often starving because she hasn't received a customer for two days; Parul, about 14 years old as well, sold by her needy stepsister to traffickers during the great famine of 1974 shortly after her father's death; Fulmoti, whose fate went downhill after giving birth to an unwanted child; and Golapjanburi, once a beauty, owner of a brothel, now waiting for death in the severe pangs of life.

Amidst all their stories, Yeasmin's stood out to me—an educated girl and survivor of sexual trauma during the liberation war but later on denied by all her relatives even as she is named a Birangona—the official title given by the government to women sexually abused during the war. Mapping the trajectory of her experiences after the war, Rizia Rahman explores how real war-heroines are identified through the presence of physical markers, such as ill health and loss of mental stability, or are labelled as an "abnormality", rejected by their family and the community. Although activists have tried to recount individual accounts of Birangonas over the years, society has only exemplified them by glorifying their trauma.

Rokter Okshor upholds a brutally honest and painful account of the industry in which many of them, including this novel's characters, operate on their own set of rules, where humanity is often a silent observer. In the thin volume of only 110 pages, Rahman builds strong visuals with the vivid imagery, transporting readers to besmirched lanes with dim lights, bright colours, claustrophobic rooms, and whiffs of incense, sweat, and alcohol.

Her prose is bitingly haunting, which makes for a heart-rending read. And her characters themselves are complex, submissive to their fate yet constantly rebelling against it as they try to maintain an upward mobility in their own world. Though upsetting, the violence in this book often occurs off-page and is not sensationalised. There are moments of friendship, warmth and community between the women in an environment designed to push them into competition and self preservation. Alas, these are fleeting, disappearing in a whiff.

Rokter Okshor is a tale of the wronged rather than the apparent wrong-doers. It is a work of art that humanises, even as it narrates, the violence present in Bangladeshi women's lives. For these women, it was a war of existence, a severe fight to survive which did not end with the country;s Liberation War. Through novels like Rokter Okshor, Rahman redefined the meaning of morality and ethics and, most importantly, compelled readers to rethink prejudice.

Sheha Saha is a writer, spoken word poet and artist. Reach her at sheha.saha001@gmail.com.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments