Lessons from the diplomatic roads not taken

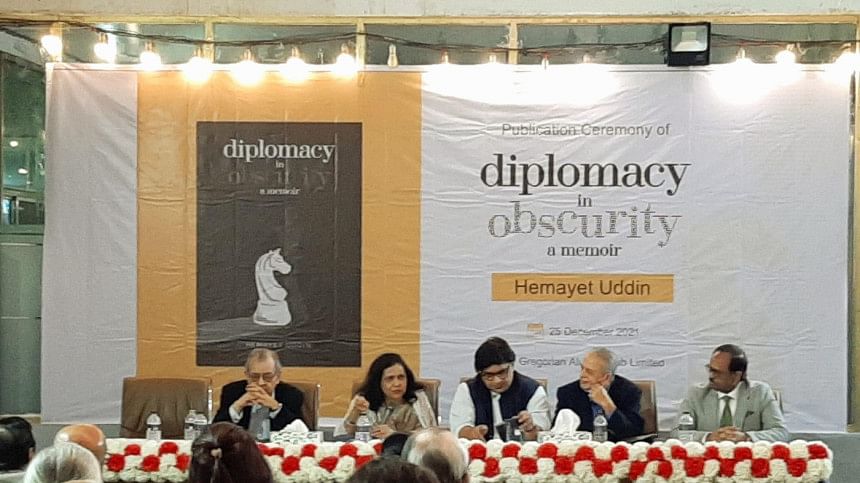

Neil Armstrong's "giant leap for mankind" comes to mind while reading Hemayet Uddin's Diplomacy in Obscurity: A Memoir (University Press Limited, 2021). His illustrious walk from a junior Foreign Ministry official to becoming this country's Foreign Secretary and donning the Ambassador/High Commissioner's hat reveals eight platforms in 20 chapters where Bangladesh's contours could have been reconfigured. Did our own idiosyncrasies/fallibilities hijack our own "giant leap" as it flew by our window?

Hemayet Uddin is no run-of-the-mill ambassador. Determined to "bring to light the life and work of a diplomat working in the shadows of obscurity", he leaves enough food on the table for aspiring plenipotentiaries to get a head start. Yet it may be his constant invocation of a global framework with some sort of a cutting-edge leftover that invites Dhaka's growing and increasingly thirsty pool of international/global relations students/scholars for a treat.

Each of his 20 chapters carries a nugget or two of contemporary relevance. From those 20, at least eight important platforms illustrate how learning about the past helps us understand the present more coherently (first lesson, dear neophyte). Putting his professional life in chronological order, those platforms include the United Nations, India, Myanmar, Europe, the 1990 Iraq War, the United States, Southeast Asia, and China. No dismay, mind you, if anyone interprets that to be a rough chronology of post-Cold War International Relations pressure points: the duty of a diplomat is arguably defined as much by his/her passion and circumstances as agendas and plans.

With the United Nations, Uddin alerts us to the historical roots of the currently imperative UN General Assembly Millennium Session of 2000 (Chapter 2). While Chapter 3 details two misperceptions in Bangladesh-India relations (over land boundary and Bangladesh as a security threat to India), Chapter 4 narrates two missed bilateral opportunities (the India-Myanmar gas pipeline through Bangladesh becoming a pipe dream and a gigantic Tata foreign investment evaporating). These set Chapter 5 up to dig out the roots of the current Rohingya influx from 1978, leaving chapters 6 and 7 to articulate why Cox's Bazaar and the Chittagong Hill Tracts, a region crowded with Rohingyas, have long remained sensitive to Europeans, especially the Dutch, for quite different reasons: treatment of ethnic minorities and flood control.

Former Ambassador Hemayet's professional "heart" is discernible from Chapter 8: his path-finding role in building Bangladesh-US. relations. While Chapter 8 informs us why dispatching Bangladeshi troops to evict Saddam Hussein from Kuwait in 1990 was pivotal in entering US policy-making networks in Washington, DC, Chapter 9 tells us of how he learned of Washington's "lunch culture" (and why it is significant to foreign diplomats). In Chapter 10 the significance of being invited to US presidential election conventions (in his case, witnessing Bangladesh's "dark horse" candidate, Bill Clinton, ascending from out of nowhere, eventually to win), is articulated. What is revealing about Chapter 11 is his reference to "the other South Asia," to which Bangladesh was "relegated", along with Nepal and Sri Lanka, in "Beltway" language. How Uddin made Bangladesh postage stamps "Unsinkable" exemplifies the type of nuances beginners must learn to be noted while climbing the diplomatic ladder. This is done in Chapter 12, while Chapter 13 exposes how bedfellows can be made even out of adversarial thinking (General Ershad's nationalism meshing with Douglas Coe's evangelism).

While Chapter 14's "Tastes like chicken" title marked Uddin's US sayonara, how it was officially praised by Congressman Gary Ackerman opened a window of enormous respect― especially as Uddin was China-bound (thus ideally placed to mediate anything between two increasingly fractious power contenders today). Nonetheless, chapters 15 and 16 inform us of his highly salutary presence in Thailand and Cambodia beforehand. Chapter 17 is about China, where he learned Bangladesh's name to be "Munjala," but more significantly promoted, as described in Chapter 18, Munjala's credentials to host a Non-Aligned Movement conference. Even North Korea's "mighty 'K' word" (the Kim dynasty) enters his picture in Chapter 19, leaving for Chapter 20 to take us through the illustrious Ambassador's first post-career position, back where his career jettisoned, in the Middle East, this time with the Organization of Islamic Countries. Given his self-admitted "miserably paltry" pension (p. 169), this was as hearty an ending (or start of a new career?), as any.

Paltry may have been his pension, but former Ambassador Hemayet still leaves a feast for diplomatic and scholarly aspirants to digest in shaping their own career. Minus those two misperceptions and two missed opportunities, Bangladesh-India relations might have reconfigured the region. We could have had several infrastructural projects crisscrossing Bangladesh and reinventing long-lost channels with both South and Southeast Asian countries if the 1975 Bangladesh-India Land Boundary Agreement that was signed by Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and Indira Gandhi did not wait until 2015 to be ratified (by Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina and Narendra Modi, though Manmohan Singh should be credited for signing the document in 2011, with Modi finding the votes needed). Similarly for the Myanmar-India gas-pipeline through Bangladesh: forget the royalties we would have collected, but just the idea of Myanmar taking a million-odd refugees back today would have had a solid anchor to stand upon.

More than that is the crucial learning our leaders make. Their bargaining is at the top, and trickling down to Main Street is usually very uphill. Uddin wasted no time in alerting us how breaking into the "lunch culture" or tapping into prominent vested groups, like Coe's National Breakfast Prayer Group, is crucial for the country to knock on policy-making doors. Yet, if the lessons learned ripple to the public, populist sentiments behind the BJP-bashing of Bangladeshis, or more significantly, the Indian perception that led to this BJP-bashing―of Bangladesh being a security threat by harboring armed Indian dissenters (United Liberation Front of Assam's Anup Chetia that Uddin talks about in pp. 32-4), dampens enormously. Indeed cultivating vox populi might have helped the Bangla-India Land Boundary Agreement not have to wait until 2015 to be ratified. Unfortunately Bangabandhu was not there to do it after 1975, nor too Indira for too long, but the larger issue of not just tortoise-like information-flows but also misinformation between ministries ought not to be there, not in this internet/social-media age when the public will get to know of such developments from other sources, often with distorted meanings. Dear Neophytes: Are your diplomatic juices still flowing given this touch of James Bond?!?!

Much more must be said about the immediate imperative of having the right infrastructures to suit the wish-list. Uddin noted how we could not host the world's second largest international organizational summit (the Non-Alignment Movement's quadrennial) because we did not have the hosting wherewithal (one by-product was the Bangladesh-China International Convention Center, hastily built for a NAM summit, but just a little too little and late). As Munjala aspires to become a developed country by the 2040s, we hope the necessary infrastructures necessary for "graduation" to that level can be installed now, not in the 2040s.

From the former Ambassador, we learn so much about doing the necessary homework, even disrupting vacations, as he did to promote Bangla-Thai relations. That might be an appropriate point to end on: how we are desperately negotiating free-trade agreements with Southeast Asian countries to fit our developed-country plans. To avoid "Johnny come lately" consequences, the foremost lesson for policy-makers from the book is to jump in, think ahead, galvanize the support-base, and only then await results, armed with wisdom and wit at all stages.

For all those aspirants, particularly of global studies who can help offset the diplomat's workload, channels into the Foreign Ministry is an idea whose time has urgently come. Opening "desks" or "think-tanks" and recruiting bright university students can help any ministry to shine, its diplomats to glow a little extra, and every "mission impossible" task a delight to undertake. This may be the book's most valuable lesson, so future efforts no longer remain in "obscurity."

Professor Imtiaz A. Hussain is Advisor, Global Studies & Governance Department and Executive Director, Center for Pedagogy, Independent University, Bangladesh (IUB).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments