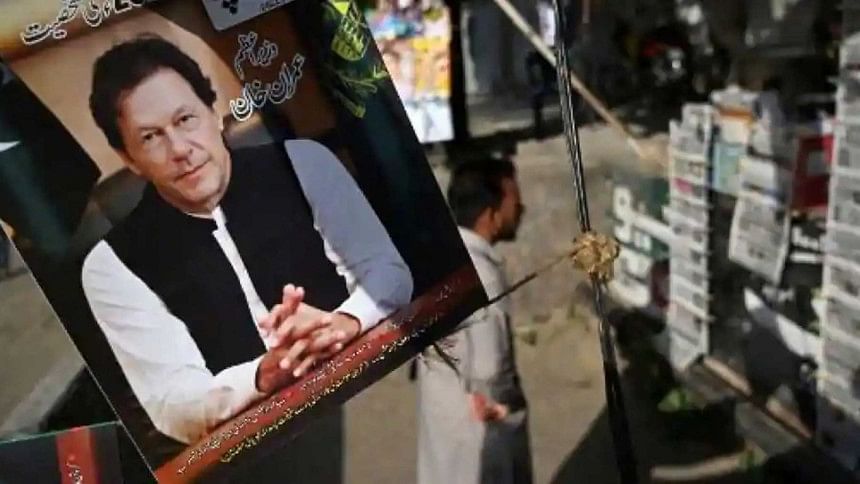

Imran Khan’s downfall and the judiciary’s role in it

A fortuitous combination of several factors in the past few months have brought down the Imran Khan government in Pakistan. In a sense, the writing was on the wall since early March, when the opposition tabled the no-confidence motion in the lower house of parliament. The citizens' movement for the past several months against the mismanagement of the economy and the unity of opposition parties set the backdrop. The army's unwillingness to support its blue-eyed boy was an important factor, and the discomfort both within the country and outside with the foreign policy pursued by the government contributed to the turn of events. But in the end, undeniably, it was the Supreme Court of Pakistan that pulled the curtain on the Imran Show—at least for now. The active role of the country's highest court, headed by Chief Justice Umar Ata Bandial, became the decisive element in the political and constitutional crisis that began to unfold in March, but particularly on April 3, when the deputy speaker abruptly rejected the no-confidence motion. It was followed by Prime Minister Khan's decision to request President Arif Alvi to dissolve the parliament, which he did immediately.

Imran Khan's shrewd move to avoid being fired from the job caught the opposition parties off-guard and apparently delivered him a strategic victory. In this move, especially how the no-confidence motion was thrown out, Khan unwittingly opened the door for the judiciary to intervene, because it involved the interpretation of the constitution. The Supreme Court, being the protector and the ultimate interpreter of the constitution, had the opportunity to step in. The modus operandi of the no-confidence motion's rejection was an open invitation to the court, because even a layman would have understood that it was a flagrant violation of the constitution. The Supreme Court intervened even before the opposition parties reached its door. After four days of hearings, the court delivered the verdict—that the way the no-confidence motion was rejected breached the constitution, and a subsequent series of events—and the dissolution of parliament was reversed as well. The court further instructed that a vote on the motion must take place by midnight on April 9.

It is in this context that the question arises whether this role of the court was an example of the independence of the judiciary in Pakistan, or whether the court played this role on behalf of some other force.

The history of Pakistan's judiciary has two strands. One strand is the unwavering support for the executive branch and legitimising its misdeeds. The other one is the stand taken opposing the executive's anti-constitutional activities.

At the time of Pakistan's founding, it was promised that the judiciary would enjoy absolute independence. This was stated in the "Objective Resolution" passed by the Constituent Assembly of the country in 1949, which played the role of the de facto constitution until 1956. A few decades later, the 1973 constitution also said so against the backdrop of a new political reality and the new geography of Pakistan. However, this promise was never kept. Instead of acting as an independent coequal branch of the executive, Pakistan's judiciary has served as the instrument to legitimise the executive's actions.

There have been several instances of Pakistan's courts providing justifications for the executive. The first incident happened in 1955. In October 1954, Governor General Ghulam Mohammad dissolved the Constituent Assembly and declared a state of emergency on the pretext of "a deadlock in parliament." But the fact of the matter was that the Constituent Assembly was trying to strip the governor general of the power to sack ministers. Maulvi Tamizuddin Khan challenged the dissolution of the Constituent Assembly in the Sindh court in February 1955. The court ruled in his favour. But the Supreme Court, headed by Chief Justice Muhammad Munir, overruled the Sindh court's verdict.

It had been rumoured that the governor general had already received assurances from the chief justice that, whatever might happen in the Sindh court, the Supreme Court would rule in the governor general's favour. In another judgment, it was later admitted that in Tamizuddin Khan's case, the governor general's power to make laws had been circumscribed. But in a third case, on the pretext of the absence of the Constituent Assembly and that the constitution had not yet been promulgated in the country, the Supreme Court granted the governor general the right to make laws. The court's argument was based on the "Doctrine of State Necessity," which means that "in a situation of emergency or exigent circumstance, a state may legitimately act in ways that would normally be illegal." In other words, it provided the legal veneer to Ghulam Mohammad's unconstitutional acts. These three cases offered a clear idea that the judiciary in Pakistan had become subservient to the executive.

Since then, military rule has been imposed three times in Pakistan and has been legalised by the court each time. The first military rule in Pakistan began on the morning of October 8, 1958, with the military rule of General Ayub Khan. Chief Justice Munir legitimised him with the theory of "revolutionary legality." Under that theory, courts would endorse a coup that "satisfies the test of efficacy and becomes a basic law creating fact." A Pakistani court also provided legitimacy to Yahya Khan's military coup d'etat of 1969. However, after the establishment of civilian rule in the country, it said that the military rule had no constitutional validity. Yet, in 1977, when General Zia-ul-Haq imposed military rule, the court did not say anything to him, instead when Begum Nusrat Bhutto challenged it, the court dismissed it citing the "Doctrine of Revolutionary Legality." As the cases filed in the court after General Pervez Musharraf seized power in 1999 were piling up, the judges of the court were forced to pledge allegiance to the law enacted by Musharraf under a law like that of Zia.

There are other instances where the judiciary had taken a different stance—at least the justices had stood up to the executive. General Zia in 1981 promulgated an order called the Provisional Constitution Act (PCO), which required all judges to take a fresh oath. However, 16 judges lost their jobs and three refused to be sworn in. The remainder, however, succumbed under pressure. This slight resistance became an example of respect for the constitution and the rule of law among judges. It is far short of institutional repudiation to military rule, but a glimmer of hope nevertheless. Before Zia-ul-Haq dissolved the parliament in 1988, Article 58 (2) was added through the eighth amendment of the constitution, which gave him unlimited power. However, after his death, the court said the dissolution of parliament was unconstitutional.

We witnessed a major role of the judiciary in 1993. In April, President Ghulam Ishaq Khan dissolved parliament to oust the Nawaz Sharif government. Nawaz Sharif returned to power in May, thanks to the court which threw out the president's order as unconstitutional. The strengths of the judges and lawyers and their commitment to the laws were on display after Chief Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry was sacked in March 2007 by President Pervez Musharraf. Movement across the country against Musharraf's decision rocked the nation. A full bench of the Supreme Court in July voted 10-3 to declare the president's decision unconstitutional and reinstated the chief justice, and quashed the charges brought against him at the Supreme Judicial Council and the law which the president used to dismiss the chief justice.

The second phase of the court's direct confrontation with Musharraf took place in late 2007. When the court challenged the legality of the October presidential election, Musharraf dismissed 60 judges, including Chief Justice Iftikhar Chaudhry, and placed him and other top judges under house arrest. This galvanised the movement against Musharraf, leading to his fall from power. Another evidence of the court's desire to exercise its independence came in 2012 when the court sentenced Prime Minister Yusuf Raza Gilani on charges of contempt of court and eventually forced him to resign.

Those familiar with these two strands in the history of Pakistan's judiciary will be able to understand that the conduct of Chief Justice Umar Ata Bandial and the Supreme Court in the last few days was important, but it is not unprecedented. It cannot be claimed that the courts in Pakistan are not influenced by the manoeuvring of the country's political forces, but there is no evidence to support the claim that the courts in Pakistan were instigated or influenced by other forces in judging the constitutionality of Imran Khan's government's conduct. Fortunately, it didn't have to intervene further as the vote was held at the last minute. On the other hand, to prevent the downfall of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) government due to defections, the court ordered that Article 65 (A) of the constitution must be considered during the no-confidence vote. This article includes the anti-defection provision of the constitution and stipulates that a member of parliament will lose his/her membership if he/she defects. As such, it is erroneous to suggest that the court opened all the avenues for the fall of the government in the name of protecting the constitution, but instead the court's conduct appeared to be an attempt to protect the constitutional integrity of the legislative process.

Ali Riaz is a distinguished professor of political science at Illinois State University in the US, and a non-resident senior fellow of the Atlantic Council.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments