Inflation sprints to 17-month high

Inflation in Bangladesh rocketed to a 17-month high in March driven by higher food costs as global uncertainties stemming from the Russia-Ukraine war and supply chain disruptions show no sign of abating, official figures showed yesterday.

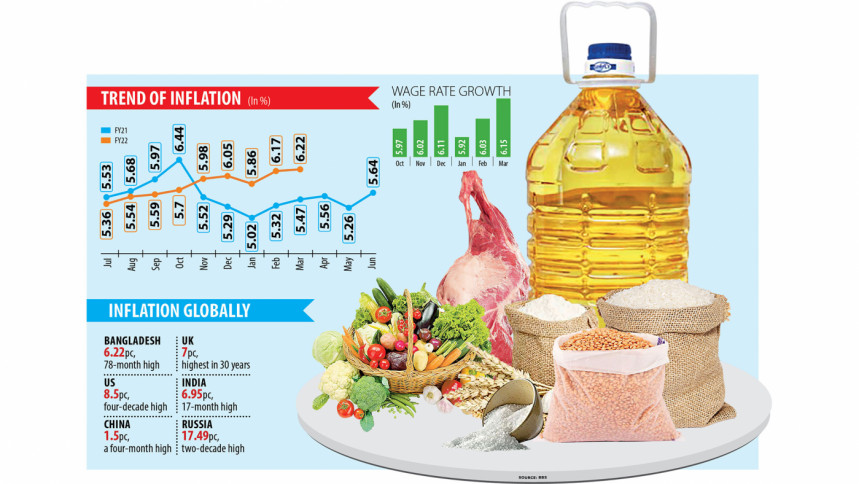

The Consumer Price Index came in at 6.22 per cent last month, up from 6.17 per cent a month ago, according to the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS). This is the highest since October 2020.

Food inflation rose 12 basis points to 6.34 per cent, amplifying suffering for the poor and the lower-income groups since food accounts for about half of their consumption basket.

What is even more depressing is that wages have failed to keep pace with the rising cost of living.

In March, wages rose by 6.15 per cent against 6.03 per cent in February.

"The increase in food inflation was expected and is likely to increase further in the near term given the elevated commodity prices in international markets and the pressure on the exchange rate," said Zahid Hussain, a former lead economist of the World Bank's Dhaka office.

Non-food inflation fell slightly to 6.04 per cent. It was 6.10 per cent in February.

Inflation in rural areas was up three basis points at 6.52 per cent last month. Food inflation rose nine basis points but non-food inflation declined 10 basis points.

Urban inflation went up by 10 basis points to 5.69 per cent, led by a 19-basis point rise in food inflation, which stood at 5.49 per cent.

Higher inflation is not just a Bangladeshi phenomenon. Inflation is hitting new peaks in most countries because of skyrocketing energy and food costs, supply constraints and strong consumer demand.

For example, inflation in the UK stood at 7 per cent in March, the highest in 30 years.

US inflation surged to a new four-decade high of 8.5 per cent and the eurozone inflation climbed to 7.5 per cent, about a two-decade high. It was 6.95 per cent in India, a 17-month high and 1.5 per cent in China, a four-month high.

Hussain says the real wages of low skilled workers have declined, more so in fisheries and construction.

"This is likely to have a serious adverse impact on poverty and inequality."

The question is what to do about it.

The automatic correction mechanism that works through the rise in nominal interest rates is inoperative because of the cap on lending rates. This has severely constrained the role of monetary policy in inflation management, according to the economist.

He says all the Bangladesh Bank can do is to keep the exchange rate stable, but that risks losing precious foreign exchange reserves even further.

The Bangladesh Bank capped the deposit and lending rates for banks in April 2020. It put a similar ceiling on the interest rates for non-bank financial institutions on Monday – at a time when countries around the world are raising key rates to contain runaway inflation.

"Exchange rate adjustments have become unavoidable not only to maintain reserve adequacy but also to stem the erosion of the economy's competitiveness, given that currencies of many competitor countries have depreciated even more. But this risks further increase in inflation," said Hussain.

Fiscal policy can provide some respite through increased subsidisation of essential commodities and cash transfers to the poor and the vulnerable, he noted.

"Better targeting will be critical in this sphere to keep the total subsidies and transfers within manageable limits."

Sayema Haque Bidisha, research director of the South Asian Network on Economic Modeling, called for identifying labourers and fixing a minimum wage for them.

Then the government can move for putting in place a system to adjust wages in line with inflation, she said.

She says the government should also introduce identification cards so that it can extend some form of social safety net assistance to them when they need it most.

"Our ultimate target would be introducing an unemployment insurance scheme," said Bidisha, also a professor of economics at the University of Dhaka.

Countries could expect a higher inflation rate for the rest of 2022 and beyond.

For Bangladesh, the inflation outlook has worsened due to the war in Ukraine and associated sanctions that resulted in higher global commodity prices, said the World Bank in its latest report.

In a write-up yesterday, Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, economic counsellor and director of the research department of the International Monetary Fund, said inflation has become a clear and present danger for many countries.

Even prior to the war, it surged on the back of soaring commodity prices and supply-demand imbalances.

"We now project inflation will remain elevated for much longer," he said.

Gourinchas urged central banks to adjust their policies decisively to ensure that medium- and long-term inflation expectations remain anchored.

"Several economies will need to consolidate their fiscal balances. This should not impede governments from providing well-targeted support for vulnerable populations, especially in light of high energy and food prices."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments