Parallel Realities, Peripheral Existences: Saikat Majumdar’s The Middle Finger

The imposter syndrome that Megha struggles with is nearly universal today, and we almost take it for granted.

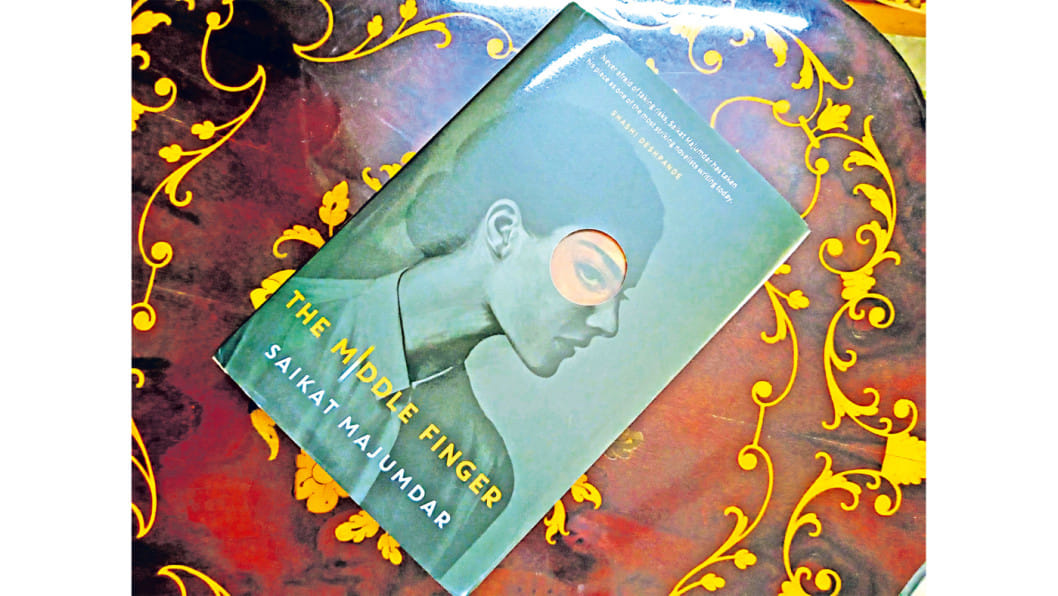

The intriguing image of a woman's eye peering through a hole cut into the glossy book jacket suggests that there is more to Saikat Majumdar's The Middle Finger than meets the eye. It is a novel about the peripheral and parallel spaces and existences that we tend to deny. It is also about opening one's eyes to the most important things in life, which may not be in the accustomed structures that we tend to take as the absolute truth.

At the centre of The Middle Finger stands Megha Mansukhani, a graduate student at Princeton who leaves the programme in the middle of her dissertation because she cannot connect with her studies. The reality that hits her is terrifying: "The world didn't give out jobs to people who had thrown their dissertations away. Her advisors were real about these things, they didn't want to keep illusions scattered."

Megha's plight is cushioned by a one-year fellowship at Princeton, but the fear of being jobless or tackling adjunct teaching at best looms right behind it. The perks of her lonely life are getting published in literary journals and going grocery shopping—one gives her a sense of belonging and the other freedom. She takes comfort in her sparsely furnished, windowless basement apartment in New Brunswick because it's a far cry from the "violent silence" of her perfect and cold childhood home in Alipore, Calcutta. That she works well in vacant apartments reflects the emptiness of her typically fragmented modern life—the intense focus on work that wipes out everything else. In such a competitive and goal-oriented existence, people learn to disregard matters that are personal and meaningful.

But The Middle Finger is also a poetic novel about a poet who cannot disregard the pains she sees around her. The suffering of others finds expression in Megha's writing, while she herself grapples with imposter syndrome: "It was like sleeping with someone and gossiping about the lives they had revealed under the blanket. It was cruel. Her words were cruel. The guilt nudged her. She laughed them away. They nudged her again." Something is missing that makes her unable to connect with her life, and Megha's quest is to make sense of her own trajectory.

Spanning two continents and cultures, The Middle Finger brings together two different times and lives. When Megha returns to India to teach at an elite institution, she was only exploring an option of a different life and seeing if she could finish her discarded dissertation. Her western education sets her apart in Delhi and she exudes an elitism that she lacked many years ago when she lived in the same city with her divorced mother who could not earn respectability in spite of her well-paid job.

In her new role as a creative writing professor at Harappa University, Megha feels uneasy and conflicted. She enjoys performing in front of her students, but she's uncomfortable about the fact that this exclusive college costs far beyond what an average Indian student can afford. Most of her students are from rich, well-connected and influential families. Yet, when her domestic help Poonam asks her to teach English to the poor women at her local church, she declines. Poonam herself also asks to be Megha's pupil. Unconsciously, the class division is stark in Megha's mind: "She was not her student, she could never be. She was too far away." Megha might be angry and frustrated enough to tweet in the middle of her class when she hears of a black girl being shot by police in Atlanta, but she is not ready to take the step that can bridge her life and Poonam's.

This is where the story of Eklavya in the epic Mahabharata comes into play, alluded to by the novel's title. That story remains relevant even today for the Bheel and Bhilala archers of Alirajpur and elsewhere in India who use their middle fingers instead of their thumbs as a sign of respect to their ancestor Eklavya and as a symbolic protest against Drona and Arjuna. By alluding to Eklavya, Saikat Majumdar questions the authoritarian patriarchal setting where fixed social status, caste and gender roles destroy or suppress human emotion and authenticity.

Poonam could have been just an ordinary domestic helper, but Megha unknowing touches her life through her poetry. Poonam is able to deeply apprehend Megha's poetry and use it to enliven others in a way that the best of Megha's elite students cannot. Her story intersects the novel like the discordant cry of chickens being slaughtered in the Calcutta market where she grew up—and where she returns after Megha rejects her. Megha is able to connect with her only when she recognizes her own pain—the idyllic childhood she could have had in Calcutta if her parents had not divorced. She had been to the best schools, but she never recognized the void within her. Poonam appears in Megha's life like Eklavya, the "artless, honest, unsophisticated forest dweller," questioning the validity of the reality she had created for herself.

The imposter syndrome that Megha struggles with is nearly universal today, and we almost take it for granted. Early in the novel, Megha's friend Rory claims, "Literature sits uneasy in India." He further explains, "English is taught the way the British wanted it taught in the 19th century. But being a Bharatnatyam dancer has taught me whole new things about the life of words in the subcontinent." For me, The Middle Finger is like a carefully choregraphed dance-drama where many lives and many worlds collide—a moving story of class, cultural and racial tension.

Sohana Manzoor teaches English at ULAB. She is also the Literary Editor of The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments