We are the 99%: From factory workers to the new working middle class

In 1886, three years after the death of Karl Marx, the May Day movement took place. Earlier, in his book Das Kapital, Marx analysed the simultaneous rise of capitalism and the development of the working class. He cited many reports of factory inspectors as references to describe the precarious condition of workers at that time. Almost 150 years later, in Bangladesh, the condition of factories and workers remains almost the same. But there is no authentic documentation of it, as the government is more interested in recruiting industrial police than factory inspectors, because that's what the owners want.

There is no instance where the industrial police have ever brought anyone from the owners' side to account for wage theft, torture or cheating, but their action against the workers is decisive. The industrial police have thus been transformed into a tool to arrest or harass workers at the owners' behest. The latter bestows gifts, including vehicles, to the police. What can the workers give?

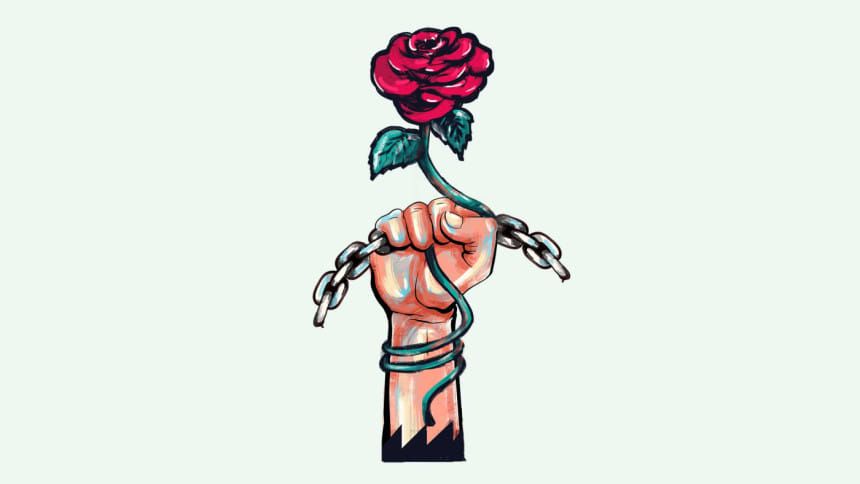

Wage workers are an essential cog in the capitalist machine, the driver of its growth through the centuries. We have seen how they were exploited during the Industrial Revolution in Europe as well as the United States. There were no fixed working hours, no decent wages. Filled with resentment at the inhuman condition in which they lived, the workers, including women and children, organised themselves and held numerous protests. On May 1, 1886, 35,000 workers walked off their jobs. Tens of thousands more joined strikes in the subsequent days. There were police shootings. Workers were shot dead, and later some of organisers of strikes were hanged in a farcical trial. Their sacrifices didn't go in vain.

May Day continues to resonate with the working class in a capitalist world order. It calls on them to unite and transform into a political force to fight their continued marginalisation. For lack of unity or organised political presence can be hurtful, as we've seen in Bangladesh, in the form of a lack of security for workers, poor wages and curtailed rights. Even the Rana Plaza massacre couldn't turn the tide around. It didn't help that there has been little organised resistance to the unlimited greed of employers, corrupt officials and international profiteers, which repeatedly turned factories into mass graves.

Over the last few decades, one of the major manifestations of the changes taking place in our economy is the shift in the composition of the working class. In the name of economic reforms, many state-owned mills have been closed since the 1980s. The last major industrial establishment to be closed was the Adamjee Jute Mills, while the remaining factories are in the process of being closed or privatised. Until the 1980s, workers of these state-owned units were the main organised group among all industrial workers. Their closure, thus, was part of a long-term project to break down the organised force of workers. At present, the state-owned industrial sector is in a pathetic state. The number of unionised workers is also much less. The garments industry, which is now at the forefront, has a handful of pro-worker unions, and the condition of other labour organisations is also very weak.

On the other hand, thousands of millionaires have emerged in the country. Their goal is to earn money by exploiting workers in any way possible. They and their enablers and beneficiaries hold control over the state machinery, while workers in most industrial sectors are deprived of their basic rights such as a fair minimum wage, 8-hour working day, appointment letters, etc. Proper work environment and security are almost absent. The functioning of trade unions is still a thorny issue, and there have been instances of attacks on workers for trying to organise under unions.

Changes in the gender composition of the working class have been significant through the development of the garments industry. Most of the workers are women. Apart from this, participation of women in various professions has increased. In dealing with continued deprivation and oppression at the workplace, women workers have become a new social force. We hear stories of women's empowerment, although reports of insecurity, rape, and harassment abound.

Equally significantly, because of the current capitalist trend and arrangements, the number of temporary, day-wise, part-time, contractual, and informal workers is also on the rise in all sectors. The largest number of workers are in the informal sector, who are unorganised and endure extreme hardship. The main demand of the May Day—fair wages by working for 8 hours—thus remains a dream, not just for these workers but for the educated working class as well.

The gross domestic product (GDP) and per capita income in Bangladesh has increased manifold but without any corresponding improvement in the lives of the general people, who mostly live in poverty. Farmers, garments workers and expatriate workers run the engine of our economy but are deprived of its benefits. The costs of education, healthcare and daily essentials continue to rise.

In all regions of the capitalist world, the idea of labourer has spread far and wide into different levels of society. That is why limiting the identity of workers to the industrial sector does not illustrate the real picture of the effects of capitalism anymore. There are now many who hold a degree and belong to the so-called middle class, but their work is as precarious as that of any industrial worker. In fact, 99 percent of men and women in our society can match that description as they suffer the same uncertainty and struggles in life. Their shared misfortune and marginalisation in the hands of the financial elites has been rightly captured in the slogan—"We are the 99%". Therefore, the May Day today is not only for the factory workers, but also for the so-called middle-class educated labourers. And together, they must rise again.

Anu Muhammad is a professor of economics at Jahangirnagar University. The article was translated from Bangla by Kazi Akib Bin Asad.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments