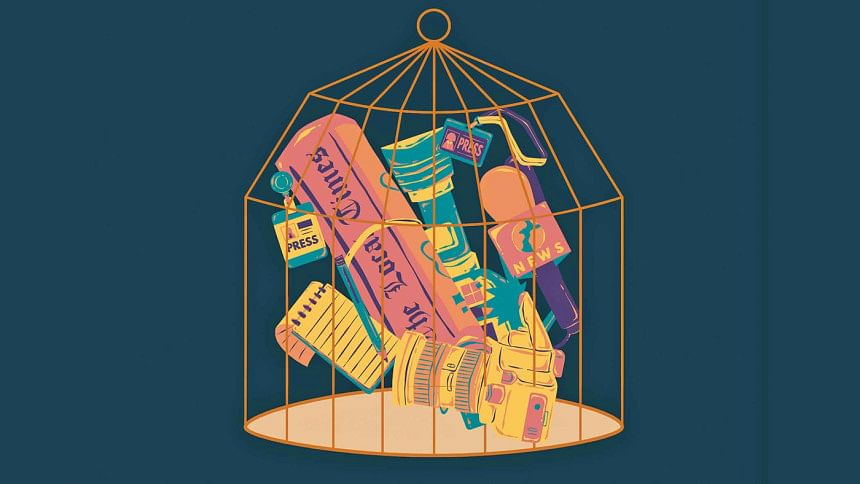

Another ring in the shackle to gag the media

Is not the media already under duress, and its function heavily encumbered by the Digital Security Act (DSA), without needing a new law which is now on the anvil of the Bangladesh Press Council (BPC)? The draft law provides for a Tk 10 lakh fine for participating in "illegal activities."

Apparently, the idea has been in the works since 2016, and the 1974 statute has to be amended to fit in such a draconian provision. For good reasons, not all members of the BPC are in accord with the suggested amendments. From reports in the print media, it appears that the draft was formulated and subsequent action was taken in a furtive manner. Some of the members were not aware of the proposal, and the necessary procedures, they feel, had not been followed before placing such a proposal to the Cabinet. Certainly, the journalist community had not been consulted either as a group or as members of the Council representing it.

The proposed punitive provisions would do anything but preserve the freedom of the press. The defining clause of the provision is ambiguous and lends itself to interpretation by the agencies involved in the process of law and order. For one thing, what is "illegal activity"? There are existing laws that lay down actions against anyone involved in "illegal activities". Why do we need to have a separate law to govern journalists? Left to the administration and its agencies, the possibility of interpreting the law to suit the circumstances cannot be dismissed out of hand. The DSA is a case in point. The worst sufferers of this very abominable legislation are the journalists. Who defines what constitutes "harm" to the image of the country and how? Is, for example, reporting extrajudicial killings, or instances of gross monetary irregularity or corruption in high places, "harming the state or its freedom or harming the image of the country"?

More often than not, the ruling party or the government has been equated with the state as several cases under the DSA exemplifies, and one cannot be blamed for thinking that the same inclination would work on the psyche of the administration when it comes to the application of the proposed amendment. On the contrary, we believe, withholding such information, in fact, is not only harmful to the image of the country, keeping it from public domain is patently anti-state. After all, corruption, or abridgments of the right to life not only abnegates the country's constitution, it puts the country's interest at stake too.

There is a raft of laws, namely, the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), the DSA, the draft Data Protection Act, and the draft Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission Regulation for Digital, Social Media and OTT Platforms (draft BTRC regulations). One wonders whether the proposed amendment betrays an element of fear or uncertainty of the ruling party and the current government. Why should a government, if it has been duly elected in a fair and free election, and claims to have the support of the majority, be so eager to add another ring in the shackles that bind the media today?

It seems that journalists and their "welfare" are occupying the mind of the administration. Not only the proposed law which, some say, is designed to sort out "errant" journalists or those who do not fall in line (with the exception of a few most have), the government is also contemplating, reportedly, to make a separate database of journalists, according to the information minister, to "restore discipline in journalism".

There is for good reason that the press (there was only the print media then) was dubbed as the "fourth estate". But since the time British politician Edmund Burke made the reference (in more of an apprehensive rather than a deferential tone), the Fourth Estate has become a metaphor for the power of the media that empowers it to hold the government and the political party, which the people have chosen by free will to run their affairs, to account, if the policies of the government run contrary to the interest of the public. But regrettably, in recent times, the media has come to be described as the "enemy of the people" by the president [now former president] of a country that holds the First Amendment to its constitution as sacred as the scripture. And in the world's largest democracy, the country's historically free press has been hijacked, according to one commentator, to do the biddings of the ruling party. In our country, too, the DSA is the sword of Damocles.

Admittedly, every institution must be guided by some rules and follow certain principles of functioning. But the administration, instead of being an enabler of free flow of information for public good, should not become a hinderer. Admittedly too, the media has not been able to acquit itself properly, but that is not because of lack of intent, but perhaps due to lack of capability in most cases.

The amendment to the existing law would also need another amendment, since the proposed punishment and the 1974 Act does not contain any punitive clause, and would alter the very underlying purpose of the commission. The preamble to the Act states, "[I]t is expedient to establish a Press Council for the purpose of preserving the freedom of the Press and maintaining and improving the standard of newspapers and news agencies in Bangladesh." And in fulfilling that particular objective of helping newspapers and news agencies to maintain their freedom, the Council, apart from its other tasks, has the duty "to keep under review any development likely to restrict the supply and dissemination of information of public interest and importance." This and the ambiguous amendment are mutually exclusive.

Brig Gen Shahedul Anam Khan, ndc, psc (retd) is a former associate editor of The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments