The root of our unhappiness: When the personal becomes political

I woke up from a Covid-induced fever dream to this news: Bangladesh has ranked seventh among the world's angriest, saddest, and most stressed nations, according to the 2022 Global Emotions Report.

Let me present to you some more jarring numbers. A total of 61.2 percent of youths (aged between 18 and 25 years) in Bangladesh are suffering from depression and 3.7 percent have attempted suicide during the Covid-19 pandemic, according to a survey conducted by Aanchal Foundation.

Mental health is an issue that has much taboo associated with it. Even in 2022, seeing a therapist is considered abnormal in many Bangladeshi households. Not many discussions are held on the issue, and even when they are, mental illnesses are portrayed as a purely individualistic crisis, rather than a collective one.

Yes, each individual needs a different method of dealing with the problems they are facing; everyone has a different story and a different pattern. But the underlying correlating factors, if not the causes, remain rooted in some common parameters. So does the approach of battling them.

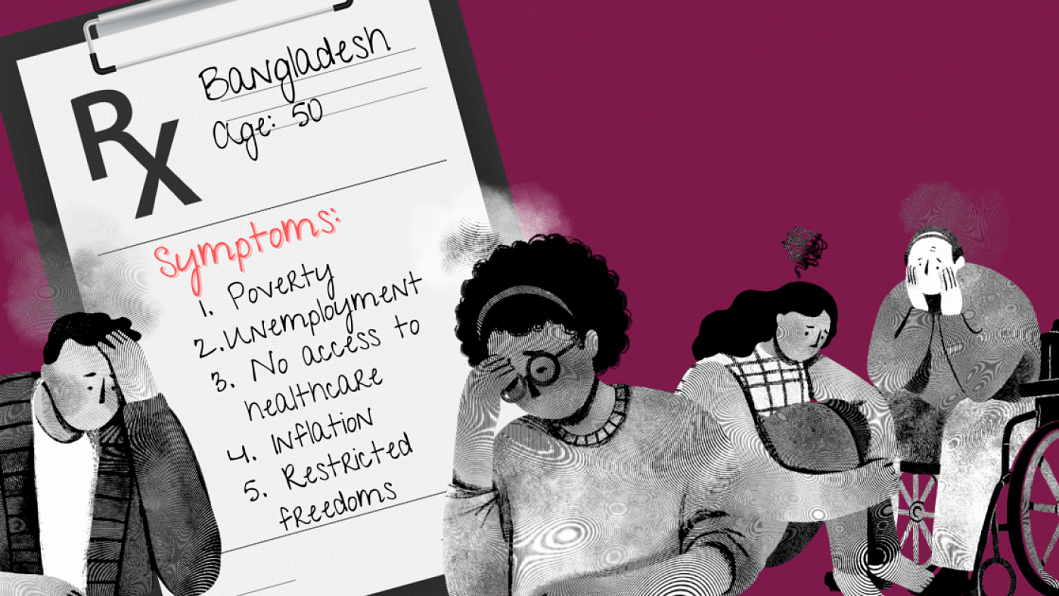

Mentioning the reasons for the unhappiness, the Global Emotions Report said there are five significant contributors to the rise of global unhappiness: Poverty, bad communities, hunger, loneliness, and the scarcity of good work.

Voila. The personal just became political.

Amid the shiny, picturesque image of development, we often forget to address the basics. We forget that the country is faced with rampant income inequality, corruption, communal and other violence, lack of justice, freedom of speech and expression, and a vulgar disparity of life in all spheres. While mental health is shaped by personal sufferings and how we process the realities of our lives to a great extent, we tend to forget that our surroundings contribute to it too – the very surroundings that are afflicted with the aforementioned issues.

Mark Fisher, in a 2012 column written for The Guardian, argued against this notion of depoliticising mental health: "Mental illness has been depoliticised, so that we blithely accept a situation in which depression is now the malady most treated by the NHS. The neoliberal policies implemented first by the Thatcher government in the 1980s and continued by New Labour and the current coalition have resulted in a privatisation of stress… It would be facile to argue that every single case of depression can be attributed to economic or political causes. But it is equally facile to maintain – as the dominant approaches to depression do – that the roots of all depression must always lie either in individual brain chemistry or in early childhood experiences. Most psychiatrists assume that mental illnesses such as depression are caused by chemical imbalances in the brain, which can be treated by drugs. But most psychotherapy doesn't address the social causation of mental illness either."

Last year, when Hafizur Rahman, a student of Dhaka University (DU), critically injured himself and eventually bled to death in the campus area, the entire university was left in utter shock. Investigations revealed that Hafiz had been on a psychedelic drug, and a misdirected war against drugs ensued. We blamed the victim, as we always do, and refused to take a long look at the underlying causes that are driving our students to the depths of despair.

Nineteen students from five public universities died by suicide last year. Of them, nine were from DU, seven from the Islamic University in Kushtia, and one each from Bangladesh Agricultural University in Mymensingh, Shahjalal University of Science and Technology in Sylhet, and Khulna University, according to newspaper reports and data obtained from the institutions.

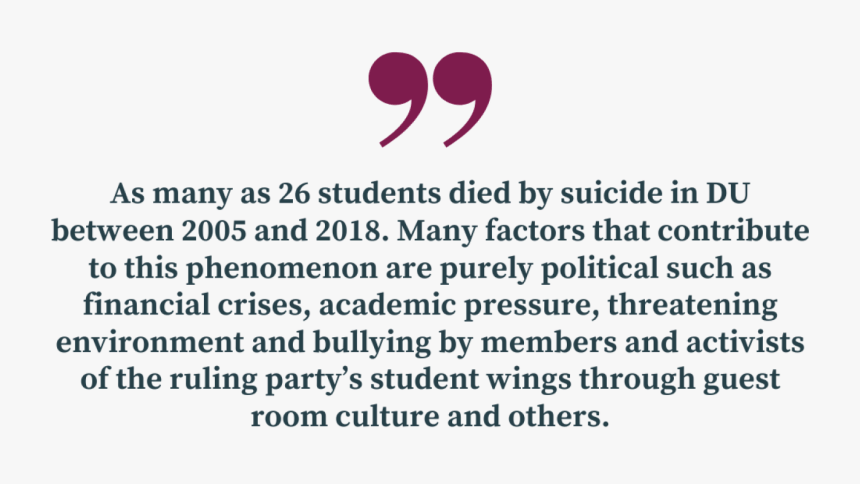

DU, from where I graduated very recently, is one of the institutions that has seen an increase in reported suicide cases. As many as 26 students died by suicide between 2005 and 2018. Many factors that contribute to this phenomenon are purely political such as financial crises, academic pressure, threatening environment and bullying by members and activists of the ruling party's student wings through guest room culture and others. Yes, personal crises also exist, but they are only elevated by the political ones.

There are only three known mental health facilities in a university of more than 40,000 students that just turned 101 years old. They are severely understaffed and cannot provide quality services despite their best intentions, from what I can tell from my own experiences and that of my friends. It's difficult to get monthly appointments, let alone weekly ones. Moreover, there is no year-long advocacy that can encourage students to seek the help they need from these centres.

I naturally assumed private universities would have better counselling facilities with their better-managed resources. However, I was surprised to discover otherwise from my friends who graduated from some of the most reputed private universities in the country. Their mental health facilities are equally underfunded and understaffed, as reported by both the current students and the alumni. Thus, the well-being of the youth, the driving force of the country, remains ignored, while so many bright minds succumb to their battle against the depression and perpetual unhappiness that this nation finds itself facing.

In the months after Hafiz's death, there were talks of bringing university students under mandatory dope tests; last month, Home Minister Asaduzzaman Khan Kamal announced that dope tests will be made compulsory for students during university admission by amending the law. Imagine the magnitude of resources needed to bring that huge a population under dope tests! Why are we focusing on that instead of allocating those resources to mental health facilities that are suffering from a scarcity of these very resources? Why are we ignoring mental health, one of the core factors behind this rampant drug dependency, once again? Or the underlying oppressive factors, like the lack of equal opportunities for every student and the terror unleashed by the Bangladesh Chhatra League (BCL) in public universities, that need a politicised call for action? Why is there no reflection of mental health in the budget allocation for the health sector, despite evidence highlighting the deterioration of people's mental health during the Covid pandemic?

The Global Emotions Report is a wake-up call for all of us. It is slightly comforting, though mostly alarming, to realise that this is not only an individual crisis, but rather a collective one. It only makes us more powerful in our fight to ensure social justice for all, to take a jab at the root of our collective unhappiness.

You are not alone. We are not alone.

Nahaly Nafisa Khan is a journalist at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments