Andrea Levy’s Small Island: Racial Conflict in Postwar Britain and a Commentary on Our World

A daughter of immigrant parents, Andrea Levy wrote mostly on the struggles of Jamaican immigrants in England. Critically acclaimed Small Island (2004) is one of her best-known books and it attempts to visualize the days before, during, and after the Second World War. The problems explored here are in many ways also relatable to the conflicts taking over the world today. Levy weaves her story through two couples, one black and the other white, and delivers a complex tale of racial conflicts and the emergence of a new world.

The speech is quite impressive, but falls flat as Bernard fails to understand one word of it due of Guilbert's accent. The incident also suggests that there is still no common platform from which both the black and white people can address each other. Even the language, even when it is English, is different. At the end of A Passage to India, the peace offering had come from a white man, "Why can't we be friends now? It's what I want. It's what you want." But friendship can only happen between people with equal standing, not between races that have been in the relationship of master and slave for centuries.

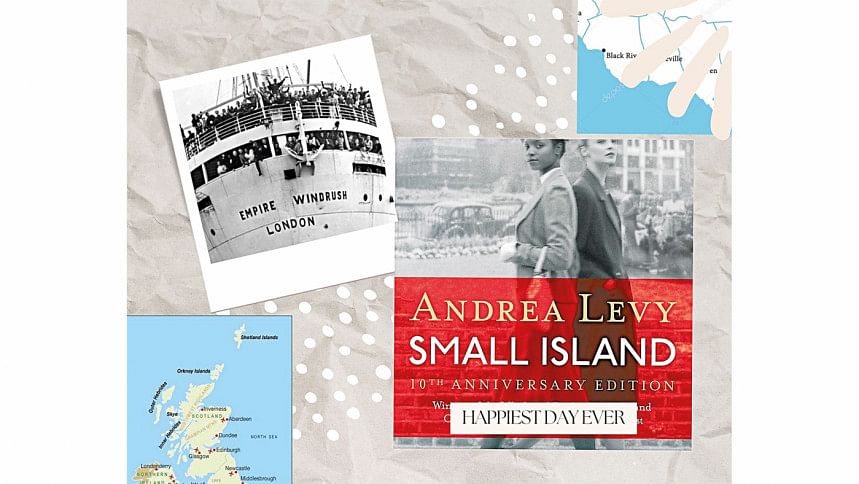

The events of Small Island are propelled by the Nationality Act of 1948. After the Great War, facing a tremendous crisis in the work force, the British Government passed the Act which welcomed people from the colonies as British citizens. The Caribbean Islands saw many of its children migrating to the British Isles. Aldwyn "Lord Kitchener" Roberts, a Trinidadian and former nightclub vocalist was a leading immigrant who had joined the Windrush, even composed a song capturing the spirit of migration:

London is the place for me

London, this lovely city

You can go to France or America

India, Asia or Australia

But you must come back to London city.

Gilbert and Hortense are a couple who left Jamaica to start a new life in England. With her lighter coloured skin and the certificate of a school teacher, Hortense had hoped to fare better than the average immigrant. But she is totally crushed when the interviewers simply reject her credentials by saying, "You're not qualified to teach here in England." She realizes that like all other immigrants, to make a living she has to rely on her skills of sewing and baking.

When Gilbert had joined the army, he was promised that he would achieve greatness beyond expectation by being able to become a wireless operator, or an air-gunner, or flight engineer. But in reality, he was forced to become a mere driver. Almost all the black people during the War were employed as common labor. The popular war-time movies display this discrimination by putting the white hero in the foreground, the black figure visible only when it is necessary to glorify the British, or American whiteness against the Nazis or communism.

Little wonder that color becomes the biggest problem for them. On the streets, they are greeted with comments like, "Oi, darkie, show us yer tail" Moreover, Guilbert and many others like him hear in silence the ignorant comments of the British who use sugar, drink tea, but have not the slightest idea where Jamaica or Ceylon might be. The inhabitants of the British colonies are taught everything about England, but when they expect the tiniest gesture of interest or acknowledgement from the so-called mother-country, they are snubbed.

That brings us to the historically famous British Empire Exhibition that Queenie, as a little girl, visits in the first chapter of Small Island. The great Exhibition was an endeavor on part of the British Government right after the First World War to showcase the British Empire. Queenie's father introduced her to it as: "See here, Queenie. Look around. You've got the whole world at your feet, lass." Then Queenie reports her encounter with the African man who surprised her and her companions by speaking clear English. Most of the British people of the time expected the people from Africa to understand only the language of drums, squat in the woods instead of using proper latrines, and devoid of all civilized behavior. Little Queenie, therefore, is disturbed with her meeting of this African man who acted more civilly than his British counterparts.

Queenie's attitude toward the colonized goes under considerable change during the War when she faces it alone in the absence of her husband Bernard. She also develops a brief romantic relationship with the airman Michael Roberts, a young airman from Jamaica. When Guilbert and Hortense come to live in her house as boarders, she is already close to giving birth to Michael's child. Her relationship with him is also historically significant. While stationed in Britain, many black soldiers developed relations with white women, most of which didn't survive the war.

Queenie's husband Bernard Bligh is a very traditional middle- class Englishman who joined the Second World War being pressurized by his peers. Even though in many respects he is a man of principle, he is also too uptight. Brought up to believe that the British are the most civilized and best among nations, his comments over the natives of India are quite racist. He is fastidious about his routine life and hence unwilling to adjust.

However, the birth of Queenie's son dramatically transforms the world for all of them. Queenie confesses to her husband about her affair, and strangely enough, a change comes over Bernard. He actually grows attached to the baby, and sings to it while his wife sleeps. He even offers to keep the child with them and rear him as their own. This gesture on Bernard's part redeems him, but Queenie is the one to reject his solution. The actual birth of the child makes her realize some basic truths about life. She asks Hortense and Guilbert to take her child and bring it up away from the scrutiny of the white gaze.

"Identity is an invention," says Hall in "Minimal Selves." Identity for him "is formed at the unstable point where the 'unspeakable' stories of subjectivity meet the narrative of history of a culture." By the end of Small Island not only little Michael gets an identity, but all the four characters virtually shift their identities in different ways. For Hortense and Guilbert, the change is most drastic as from being simply Jamaicans they become "black British," a term with a number of connotations of which they had no conception at all.

Even though Small Island ends on a kind of reconciliatory note as Hortense and Gilbert leave with Queenie's colored child, it is still far from a compromise. In their last verbal battle, Guilbert yells at Bernard:

"You know what your trouble is man? Your white skin. You think it makes you better than me. You think it gives you right to lord it over a black man. But you know what it make you? It make you white. . . . No better, no worse than me—just white."

The speech is quite impressive, but falls flat as Bernard fails to understand one word of it due of Guilbert's accent. The incident also suggests that there is still no common platform from which both the black and white people can address each other. Even the language, even when it is English, is different. At the end of A Passage to India, the peace offering had come from a white man, "Why can't we be friends now? It's what I want. It's what you want." But friendship can only happen between people with equal standing, not between races that have been in the relationship of master and slave for centuries. There might be many individual good people in both cultures and societies, but the racial tension that is disrupting the world today, has a tremendously complex history and there is no way it can simply dissolve.

Sohana Manzoor is Associate Professor, Department of English & Himanities, ULAB. She is also the Literary Editor of The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments