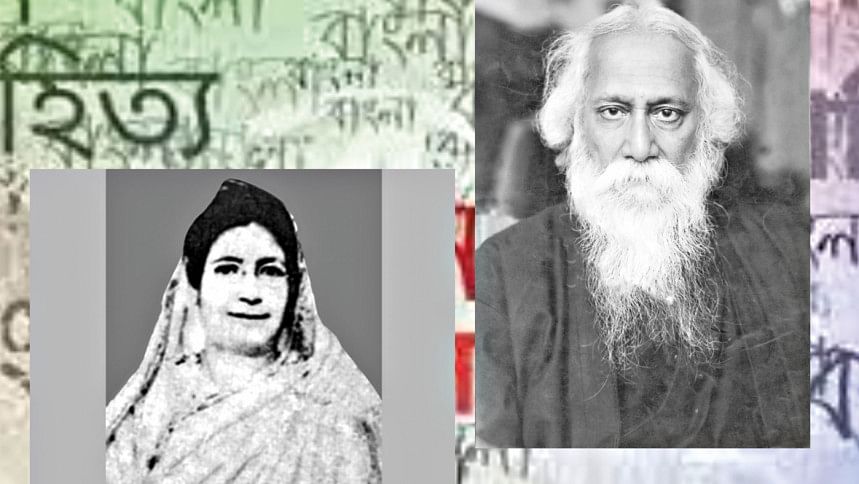

Rabindranath and Rokeya as Educational Pioneers

Rabindranath Tagore and Begum Rokeya are two iconic figures in South Asian literature and culture. However, their genius was not confined to writing alone but spread in many directions, including the sphere of education. They believed education was the key to the future of India (which included Bangladesh at the time). India could not become an independent, modern and progressive society without advancing in education and, concurrently, developing an indigenous educational model that would imbue the principles of justice, fellowship and inter-religious dialogue in the national consciousness.

Rabindranath's focus in education was to uplift the life and circumstances of all Indians, irrespective of caste, class, religion or gender. He believed in the education of feeling, sympathy and empathy and not just power and success; of spirit and the senses and not merely the mind and intellect. In Personality, Rabindranath affirms, "We may become powerful by knowledge, but we attain fullness by sympathy. The highest education is that which does not merely give us information but makes our life in harmony with all existence."

Rokeya's emphasis was on empowering women, particularly Bengali Muslim women. She argued that women's exclusion from education was the primary reason for India's social and moral stagnation. In her allegorical narratives, "The Knowledge Fruit" and "The Freedom Fruit," Rokeya proffers that India could not attain freedom from the Raj without proper educational opportunities for women. Moreover, in her utopian fictional tour de force, Sultana's Dream, she portrays, albeit in a humorous vein, how the world would be a quasi-paradise if women were allowed education like men.

Rokeya's emphasis was on empowering women, particularly Bengali Muslim women. She argued that women's exclusion from education was the primary reason for India's social and moral stagnation. In her allegorical narratives, "The Knowledge Fruit" and "The Freedom Fruit," Rokeya proffers that India could not attain freedom from the Raj without proper educational opportunities for women. Moreover, in her utopian fictional tour de force, Sultana's Dream, she portrays, albeit in a humorous vein, how the world would be a quasi-paradise if women were allowed education like men.

Rabindranath and Rokeya established educational institutions to put their ideas into practice. For example, Rabindranath set up three institutions in Santiniketan, West Bengal: Brahmacharya Asrama (1901), Visva-Bharati University (1921) and the Sriniketan Institute of Rural Reconstruction (1922). Likewise, Rokeya founded a school for Muslim girls in Bhagalpur, Bihar, in 1909 and relocated it to Calcutta in 1911.

Initially, Rabindranath's school shared a Hindu chauvinist idiosyncrasy. This is evident in the name "asram," which refers to a place of spiritual and religious retreat. However, from 1907 onwards, he abandoned all parochialism and became increasingly multicultural and global in outlook.

Rabindranath upgraded his school to a university, Visva-Bharati, in 1921, describing it as an "International University" where he wanted to unite all cultures and harmonise knowledge from different parts of the world. His primary objective behind the university was to create, as he explained in his essay "An Eastern University, "[a] great federation of men… a unity, wider in range and deeper in sentiment, stronger in power than ever."

The university progressively manifested Rabindranath's cosmopolitan education. In a letter to Nepal Chandra Ray, a fellow teacher at Santiniketan, explaining his aspiration for the university, Rabindranath wrote in 1918, "Visva-Bharati will not be a mere school; it will be a pilgrimage.

The university progressively manifested Rabindranath's cosmopolitan education. In a letter to Nepal Chandra Ray, a fellow teacher at Santiniketan, explaining his aspiration for the university, Rabindranath wrote in 1918, "Visva-Bharati will not be a mere school; it will be a pilgrimage. Let those coming to it say, oh what a relief it is to be away from narrow domestic walls and to behold the universe." Rabindranath also founded the Sriniketan Institute of Rural Reconstruction to revitalise the village life surrounding Visva-Bharati and make its inhabitants self-reliant and self-respectful.

Both Rabindranath and Rokeya encountered many hurdles in running their institutions, but Rokeya was saddled with more obstacles because she was a Muslim, a woman and a widow. For example, when Rabindranath started his school in Santiniketan, he did not have to brave any social resistance or stigma because, although the school was unorthodox, there was nothing unconventional about giving education to boys. Moreover, when it became co-educational in 1909, there was still no reprisal because the Hindus and Brahmos were generally ahead of Muslims in women's education and found nothing "unholy" in the endeavour.

However, Rokeya felt repeatedly encumbered by her gender and faith. She was vulnerable as a woman and more so because she was a widow. As a Muslim woman, Rokeya was expected to live in strict purdah and submit to the male-centric norms of society. But when Rokeya took up the mantle of educating Muslim girls, defying all social norms, the religious bigots launched a vitriolic campaign against her. Some alleged that her "companions were prostitutes and the scum of society," and others vilified her as "a whore and an embezzler of funds."

Rokeya also faced epic challenges in increasing the student population at her school, as Muslims were dogmatic and superstitious and refused to educate their daughters. They thought education would westernise the girls, make them overbearing and arrogant towards men and turn them to Christianity – the charges labelled against Rokeya herself by some of her detractors. Her reputation was so tarnished by the toxic rumour-mongers of the time that even Begum Sufia Kamal's mother refused to send her daughter to Rokeya's school, even though the two families were related.

As mentioned earlier, Rabindranath's school had a religious atmosphere initially, but he gradually moved away from it to make it more multilateral and international. However, Rokeya's school remained predominantly religious till her death, yet it also had a culturally plural milieu. Her curriculum was inclusive and modern as she taught maths, science, geography, history and public administration alongside topics in religion and home economics and introduced English as a compulsory subject for all her students. Besides, her students often staged Rabindranath's nritiya natyas and Sukumar Ray's plays and sang songs of Kazi Nazrul Islam and Atul Prasad Sen as part of their extra-curricular activities.

Rabindranath's school used Bangla as the medium of instruction from the beginning. He championed vernacular education, considering it natural and wholesome. Whilst not anti-English or anti-west, Rabindranath believed that education in any language other than the mother tongue would result in mindless regurgitation and corrupt the learner's identity by putting a wedge between one's self and culture.

Rokeya used Urdu as her medium for the best part of her life, although, like Rabindranath, she had a predilection for Bangla. She struggled to introduce Bangla at her school for many years because, Rokeya sarcastically writes in a letter to the editor of a Calcutta-based newspaper, The Mussalman, "the purdanashin Mohamedan girls in Calcutta are not willing to learn Bengali even if it is free." However, she never despaired in her mission and eventually succeeded in introducing Bangla as a subject as well as a stream in 1927. It's extraordinary that Rokeya showed such conviction in Bangla, although Urdu was her family language and spoken by Calcutta's elite Bengali Muslims. This lifelong struggle of Rokeya to introduce Bangla at her school laid the foundation for Bengali Muslims to find pride in their language and identity and, in time, stand up against the Pakistani regime when they tried to impose Urdu as the lingua franca of the newly independent nation.

In a letter to Gandhi, Rabindranath described Visva-Bharati as a "vessel" carrying the cargo of his "life's best treasure." Likewise, Rokeya cherished her school to the extent that she refrained from writing for several years, 1908-1922, only so that she could invest her best energy in the school. The duo were consummate writers but also dedicated educators who spent much of their lives revivifying their society and culture through education.

Mohammad A. Quayum is an academic, writer, critic, editor and translator.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments