Arresting gamers: An alarming threat to individual liberty

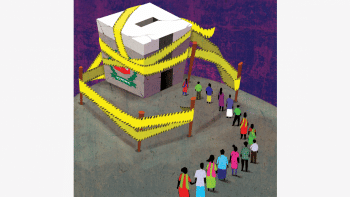

The recent arrest of over 100 youths in Chuadanga has shined a light on a problematic tendency of our police force. The arrestees were detained for participating in a PUBG (online game) tournament. The High Court Division of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh of Bangladesh (HC) directed the Bangladesh Telecommunications Regulatory Commission (BTRC) to shut down some online games that it considered destructive and harmful to the youth. More specifically, on August 16, 2021, the HC gave an interim order to ban all links/ internet gateways to PUBG. The HC's order was directed towards the BTRC, not the general people of Bangladesh. If media reports are to be believed, the BTRC tried to comply with that order. The above is stated to give a background for the upcoming discussion. This article does not discuss the legality of the police's action. It certainly does not intend to discuss the merit of the ongoing litigation. Instead, this piece deals with the paternal role taken by our police force, and its moral and political legitimacy. Essentially, Bangladesh's increasing practice of state paternalism is very alarming.

State paternalism is the practice of the state using its coercive power to make an individual do something or abstain from doing something, against their will, with the claim that the state is looking after their greater interest (such as the claims of parents in general). In a liberal state, this paternalism is acceptable, only to a minimal extent (if at all), as it greatly undermines individual liberty. It is important to note that state paternalism differs from the harm principle, which holds that limiting liberty is only justified when it is done to prevent harm to other people. In this context, "liberty" means an individual's right to act in any way they want. For instance, the state forcing its youth to get their hair cut in a certain way so that they look "gentler" would be a paternalist action, since the state is claiming to know more about the well-being of the youth than the youth themselves. The state creating a law prohibiting the violation of people's bodily integrity would be more in line with the no-harm principle.

In a liberal state, it is expected that the state will not tell us how to live a good life. It is not the state's responsibility (or something within its power) to decide what one's definition of a "good life" ought to be. Rather, the state must create a social environment of good governance where one can freely pursue their vision of a good life. In exercising paternalism, the state arbitrarily sets a standard of a good life. In a modern complex state, people's standards of morality greatly differ, and it would be illiberal to prefer one standard of morality over others. Also, as Lon L Fuller rightly argued, morality of duty (the minimum morality that we expect from our fellow citizens) can be enforced through legal coercion, but not morality of aspiration (morality of excellence/perfection). For instance, you may enforce the duty of not stealing through legal coercion, but not that of aspiring to be a good person.

Now, if we look at recent events, the police's justification for arresting online gamers, reportedly, was that these games are destroying the morality of the youth. Here, the police, as an institution performing an affair of the state, is using coercive power to enforce its version of morality over the youth. In doing so, they are deciding what would be a "good life" for the youth and what sort of life they should aspire to achieve. Not only are the police acting on their own policy, but the foundation of such policy is based on a subjective moral standard. We observed similar situations when the police force of multiple districts forced their local youth to get haircuts.

A liberal state must respect individual agency to the extent that it does not harm others. To live in society, we voluntarily sacrifice some of our liberties as part of our social contract with the state and with our fellow citizens, as long as we consider them justified. As long as one's actions are not harming others and not violating any particular laws, one must be allowed to form their own opinions and live their life according to their own wishes. As Jeremy Waldron rightly noted, our dignity demands that our decision-making ability must be taken seriously, and we must be recognised to have the ability to regulate our actions in accordance with our own understanding of norms and reasons.

Nafiz Ahmed is a lecturer at the Department of Law, North South University. Email: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments