Muting Shakespeare: Watching Richard III in Shakespeare in the Park

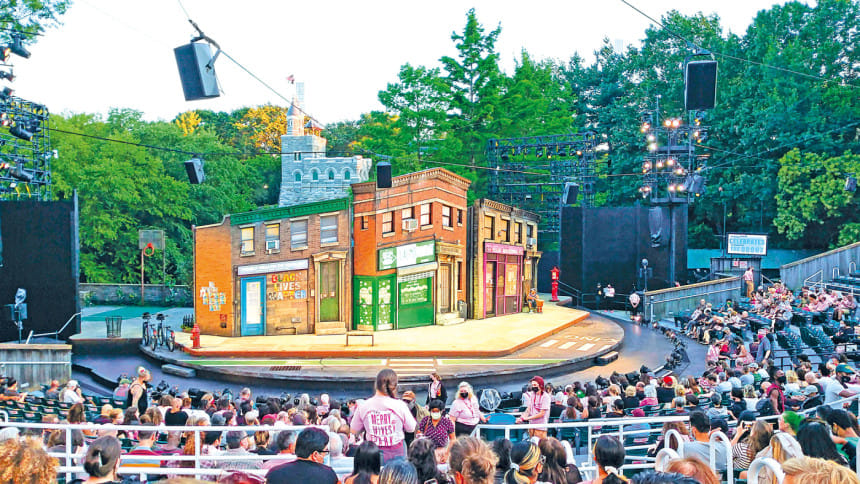

Shakespeare in the Park is a New York institution. It takes place over the summer and hosts performances of the Bard's plays free to the public. A few weeks ago, I attended a performance of Richard III at the Delacorte Theater. It was a warm summer evening and the theater was packed; after several summers of Covid-related lockdowns and the state of siege this country feels like it is perpetually under, being able to sit with one's tribe and enjoy Shakespeare felt more an event than a respite.

I had never read or watched Richard III staged before. I knew of it because its eponymous character is the only one of Shakespeare's trinity of villains that got their own play. Iago, his most arresting evil character, in my opinion, was the enigmatic antagonist motivating the paranoid actions of Othello; Edmund the Bastard, in King Lear, was even further placed from the core story as his ambitions were mediated through Goneril and Regan, Lear's daughters. Richard III, unlike the others, is front and center of the story. This play is about him and his unabashed greed for power, fleshed out in manifest deformity.

The play has become a topic of conversation in critical circles in recent years for its discourse on disability. Richard III is one of literature's most famous disabled characters and people have taken Shakespeare to task for writing physical deformations as a metonym of his immoral soul. This is not only subtext but textually explicit through the serial references to their physical deformities in other characters' dialogue. My personal favorite is how Queen Margaret addresses him: "Thou elvish-mark'd, abortive, rooting hog! Thou that wast seal'd in thy nativity/The slave of nature and the son of hell! Thou slander of thy mother's heavy womb! Thou loathed issue of thy father's loins!"

One of these is the character of Ann, whom Richard seduces to gain standing in the court. The character was played by Ali Stroker.

Now that, I laughed to myself, is an insult. No comeback for a dis that deep.

At the same time, Queen Margaret's excoriations draw their substance from Richard's physical deformities. It is in these facets of symbolic and literal meaning that we see the bigotry of Shakespeare the man of his time. Richard is a hunchback and the charges Queen Margaret levels at him for being subhuman and evil are clear to other characters in the play and by extension to the audience because of his twisted physique. Their physical disabilities mean they are not considered suitable to be regent after his brothers (one of whom he frames for conspiracy and then assassinates) die. Their disabilities mean Richard carries a stigma, or in Queen Margaret's own words is "elvisth-marked." Their body stands as a testament to their fallen nature, and therefore offers a similar diagnosis to all other differently-abled people.

The clever thing about this staging of Richard III in Shakespeare in the Park is that it took this exigence to work in a tacit conversation about disability. Richard in the play was not disabled. Played by Danai Gurira, this Richard was a strapping and muscular figure. Powerful of voice and erect of posture. Their physical definition was clear even from our seats. Rather than making Richard III stand in for differently-abled people, the play is peppered with such characters throughout, none of whom are tokenized.

One of these is the character of Ann, whom Richard seduces to gain standing in the court. The character was played by Ali Stroker. The actor uses a wheelchair and this feature is not noted in any of the scenes but played off so naturally that it does not even need acknowledgment. They wheeled around the stage accessing all parts of the open space– in classic Shakespearian fashion there were minimum props and backgrounds.

Another character is the Duchess of York, Cecily Neville, the mother of Richard III and Edward IV. This character used only American Sign Language (ASL). The actor, Monique Holt, works in making theatre more accessible to the deaf and her performance in the play added a new layer to its performance. First, seeing actors signing in scenes with the Duchess made me reconsider how contrived it is that most plays have no representation of such characters. This would not be the case because there are differently abled people in the world, living their everyday lives, and any performance that aims to represent the world must recognize that. Any story that does not represent the differently abled in its universe posits a blinkered vision.

I had never read or watched Richard II staged before. I knew of it because its eponymous character is the only one of Shakespeare's trinity of villains that got their own play.

Second, a crucial scene between Richard III and the Duchess takes place completely in sign. It is in Act 4, Scene 4, and is the final conversation between King Richard III and the Duchess. The conversation circles around themes of speech and hearing, how Richard does not heed the Duchess' sorrow over his actions. Playing off this theme, the scene was acted out completely in sign. For a few solid minutes, the theatre, enthralled in silence, left those of us who do not know ASL guessing at interpreting what was being communicated on stage. It was a defamiliarizing experience and made me realize that I simply never thought about what it is to have to navigate the world as someone who cannot hear.

In my day job, we have to be mindful of ideas of universal design to ensure teaching activities and content are accessible to differently-abled students. One of the pillars of this approach is the principle of representation – that content and information in assigned texts be accessible in mediums other than visuals or auditory. The guiding metaphor is the "access ramp," a different way to get into the structure of the building that is the course. Such imperatives certainly influenced the choices of the production to turn this play more inclusive. They chose to represent the text of the play – as best as they could – to foreground the presence of the differently abled by normalizing their presence on stage and using ASL to deliver Shakespeare's immortal words. It also made those of us who walk through the world blind and deaf to how much the world is made for us pause to think about our exemptions and what it would have been like if it were not so.

When the performance was over and the audience emptied itself into the park, we walked to the subway station. It was already 11 pm, but my mind was energized alight with thoughts about what we had just seen. The sound of the city was all around us, the distant sirens and horns and din of the people living their lives. I could hear all these signs of life but was aware of what it might feel like to have the world be mute. The play was the thing, if I may say, wherein I was able to, for a briefest of moments, catch the conscience of the otherwise.

______

Shakil Rabbi is an Assistant Professor at Virginia Tech. Though Shakespeare is far beyond his expertise, he still admires the genius and language of Shakespeare. He can be reached at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments