Death and Displacement in Syed Waliullah’s Partition Stories

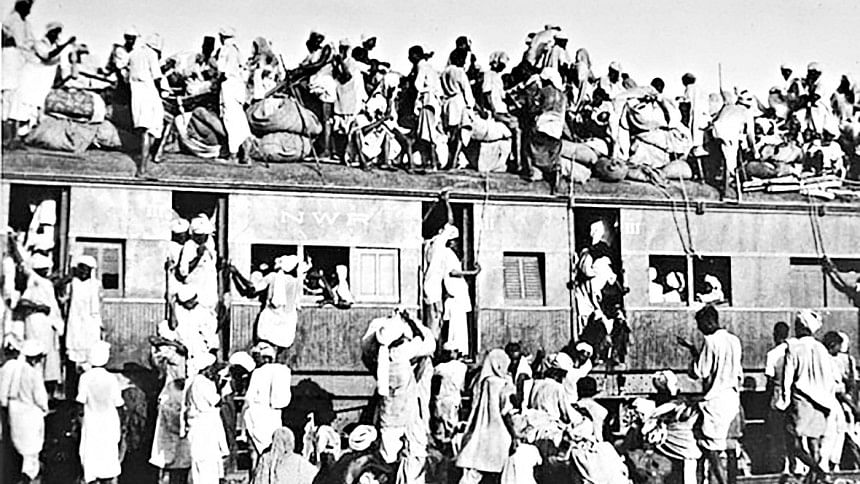

Perhaps the starkest image of the Partition, which created the two independent states of India and Pakistan in 1947, is that of the train massacres. In this vignette from Siyah Hashiye or Black Borders, Saadat Hasan Manto shows the ruthless slaughter of innocents simply because they belonged to a different community.

Rioters brought the running train to a halt. People belonging to the other community were pulled out and slaughtered with swords and bullets. The rest of the passengers were treated to halwa, fruits and milk. The chief assassin made a farewell speech before the train pulled out of the station: "Ladies and gentlemen, my apologies. News of this train's arrival was delayed. That is why we have not been able to entertain you lavishly the way we wanted to."

The train massacres inspired Khushwant Singh's Train to Pakistan (1956) and were later used by Bapsi Sidhwa in The Bride (1982) and Ice-Candy-Man (1988).

Syed Waliullah wrote two stories on the Partition, one in English, the other in Bangla. They are different not only in their language but also in structure, theme, imagery and style. Writers are often asked for whom they write. Is writing a spontaneous overflow of powerful ideas and feelings – to draw from Wordsworth – where the writer is concerned only with his or her own inspiration? Or is writing meant for an audience, adapted to meet the needs of that audience?

"The Escape," written in English, and "Ekti Tulsi Gachher Kahini," written in Bangla and then translated by Waliullah himself into English, suggest how the same writer builds on different images and perspectives for a different audience. "Ekti Tulsi Gachher Kahini" or "The Tale of a Tulsi Plant" suggests that it was written for a Bengali audience. "The Escape," first published in Pakistan P. E.N. Miscellany 1 (1950), was meant for a West Pakistani audience.

A little over a year before the Partition took place, violence broke out in Kolkata. Contemporary accounts reveal the horror that was visited on the city. Shahid Hamid, in Disastrous Twilight: A Personal Record of the Partition of India, mentions 20,000 persons being killed. Gopal Das Khosla, in Stern Reckoning: A Survey of the Events Leading up to and following the Partition of India, gives a far more modest number of 3,173 dead bodies. He notes, however, that "this figure does not represent the total number of deaths caused in the riots. Many dead bodies were burnt in houses, many others floated down the river to the sea."

However, representative Bengali writing on the Partition does not deal with riots and murders. Despite the riots that occurred in Kolkata and Noakhali, the stories that emerged from Bengal, written by writers who left East Pakistan in the wake of Partition have not been about looting and killing as about leaving, loss, and displacement, or, in the writing of East Bengali writers, the hope of a new dawn or the search for a new identity. For East Bengali writers, Partition and independence were soon followed by the Language Movement and the growing consciousness of the differences – and disparities – that existed between them and the people of West Pakistan.

Syed Waliullah's "The Escape," written when the memory of train massacres was still very vivid, is set in a train compartment full of refugees. The compartment is overcrowded but, apart from the "white, but slightly soiled, embroidered cap" which an old man is wearing – suggesting that he is a Muslim – there are no other details which would disclose the ethnic or religious background of the refugees.

The unnamed protagonist tries to befriend a little girl he sees in the compartment, but his behaviour and manner of speaking terrify her. It is obvious that the young man too is trying to escape like the others in the compartment. The young man imagines that the little girl sitting alone is a refugee who has lost everyone except the old man next to her. He offers to tell the girl a story but, even before he starts, the memory of violence that disrupts that narrative causes him to falter and even frighten the young girl. Thus he remembers the hot, still afternoon when everything but the crows were silent "Only blood, silent and vicious, oozed and oozed. . . ."

The man tells the girl that he does not want to frighten her with the story so he will leave the demons out. However, his demons, his memories which intersperse the narrative of the train journey, prevent him from continuing. The story he wants to tell the girl is never told. But the reader gets glimpses through the stream-of-consciousness descriptions of violence and mayhem. When the train stops at a station, he gets down to get some food. Then he notices a corpse guarded by two policemen. He imagines that the corpse is of a man "who had wanted to cross the border for safety, but now lay there stiff, his skull completely battered." Terrified, he returns to the compartment.

Every now and then there is a scream. The man imagines it is someone else's scream but it is his own. When the girl continues to shout about a mad man, the protagonist, not understanding that she is referring to him, looks everywhere. Failing to find the mad man, he opens the door of the compartment and steps out of the running train.

"The Escape" tells two parallel stories: the story of the young man in the train and the story of what he has seen. (Eighteen years later Waliullah would use this device of parallel stories in his novel Kando Nadi Kando). In "The Escape" the story of what the young man has seen is told in flashbacks, marked off from the narrative by italics. But these flashbacks are surrealistic scenes, not a connected story, describing the violence of the Partition in the north and west.

He had not heard the cry; silence reigned heavily. Why does blood not make any sound? It oozes noiselessly. And at that time it was oozing noiselessly Perhaps truth does not make any sound. Only what is untrue makes sounds. The man lay dead there under the deepening oblong shadow and it was true. He did not make any sound.

The story that the young man wants to tell the girl is not told nor is he able to give the message he wants to the world. All the reader learns is the fragmentary and tragic story of a young man haunted by terrible memories of massacres and killings, by scenes of dogs eating human flesh, by the sight of a man shot to death because he was seeking the safety of a country across the border. In this story, written soon after the Partition, there is no moralizing, only the horror of blood, waste, and madness.

"Ekti Tulsi Gachher Kahini" is a straightforward narrative about a group of Muslim refugees from Kolkata looking for shelter in East Bengal. Abu Rushd's novel, Nongor (1967), describes at greater length the plight of a refugee from Kolkata attempting to settle down in a different country. There are also several short stories that narrate the search for a home, among them, Ashraf Siddiqui's "Pukurwala Bari" (The House with a Pond") and Abu Rushd's "Har" ("The Bone"). Though in Nongor, the protagonist is disappointed in the backward nature of Dhaka, in "Pukurwala Bari" as in "Ek Tulsi Gachher Kahini" the rural nature of the new country is refreshing. The description of plenty in Syed Waliullah's story contrasts sharply with the conditions in which the refugees had lived in Kolkata.

Many of these people had lived all their days in the unspeakable stench and filth of Calcutta – in the sailors' quarter of Blockman Lane, in the bookbinders' quarter of Baithakkhana, among the tobacco merchants of Syed Saheb Lane, or in Kamru Khansama Lane. In comparison, the vast rooms, the wide windows like those of the indigo traders' mansions, the enormous yard, and the orchard of mango, jackfruit, and berries in the rear – all these belonged to a different world.

Discovering the large, two-storeyed abandoned house, the refugees imagine that they have no further problems, at least where a place to stay is concerned. Despite some feelings of guilt, they break the lock and occupy the house. They set about making themselves at home.

Then one day the refugees discover a neglected tulsi plant in the garden. It is a Hindu symbol, they think, and decide it has to be destroyed. They become conscious that the house they are occupying had belonged to others who were forced to leave. While the man who discovered the plant wants it to be destroyed, the others imagine the woman who must have tended that plant every evening.

Though it was overgrown with weeds now, someone had lighted a lamp every evening under this abandoned tulsi plant, too. When the evening star, solitary and bright, shone in the sky, a steady quiet flame had burned red, like the touch of crimson paint on the bowed forehead.

The image of a train also recurs in this story, but as symbolic of departure. Thus one of the refugees, who had been a railway employee, imagines the woman who tended the tulsi plant sitting at a train window, remembering the house she had left behind and the tulsi plant. Wherever she went, he thought, she would remember the tulsi plant and her eyes would fill with tears.

Syed Waliullah stresses the common humanity of the previous occupants and the present ones. The refugees who occupy the house are Muslims; the people who had vacated it were Hindus. But both groups are homeless refugees, both forced to vacate their homes for an uncertain future in an unknown place. For the Hindu housewife tending the plant might have been a religious duty, for the refugee who tends it the plant is a reminder of their common humanity, of the need for roots, for the ordinary rhythms of life which political events and upheavals disrupt. Despite religious and political differences, Waliullah suggests, the human bond remains somewhere underneath.

But the people on top who make decisions do not care for human bonds. And one day policemen arrive, accusing the refugees of occupying the house illegally. The refugees have to vacate the place. The government has requisitioned the house. After the officials leave, the refugees grow depressed. They no longer bother about the tulsi plant or about the woman who tended it.

The tulsi on the edge of the yard had begun to wither again. No one had given it water since the police came to the house. Nor had anyone remembered the tearfilled eyes of the mistress of the house.

Using the fact of illegal occupation, Waliullah writes a moving story of human feelings and also a grim reminder of the human cost of Partition.

The only woman in the story is the imagined figure of the housewife who tended the tulsi. In reality, the refugees who came from West Bengal were men, women and children – unless, as in Nongor, it was a young man who came to seek his fortune in a promised land. Many of these refugees would be disappointed, though some of them would get jobs and plots in new developments.

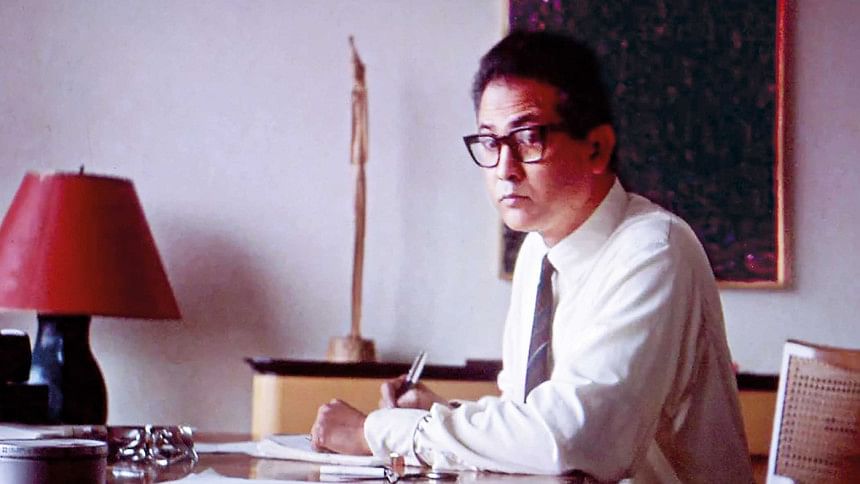

Waliullah had been working for the Statesman in Kolkata, but his family was from East Bengal and he moved to Pakistan. However, he was an agnostic as his wife Anne-Marie Waliullah says in her reminiscences, Syed Waliullah: My Husband as I Saw Him." In his early novel Lalsalu (1948) – translated as Tree Without Roots – Waliullah had suggested the fraudulence and hypocrisy behind the façade of religion. The idea that religion was not enough to hold the two wings of Pakistan together would finally lead to the creation of Bangladesh. In both his short stories, different though they are in theme and telling, Syed Waliullah questions the rationale behind Partition and describes the loss, displacement, and trauma that accompanied it.

Niaz Zaman, an academic, writer and translator, is at present Advisor, Department of English and Modern Languages, Independent University, Bangladesh. The short stories mentioned are anthologized in The Escape and Other Stories of 1947 (Dhaka: UPL, 2000).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments