Disrupted Nature and Community in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein

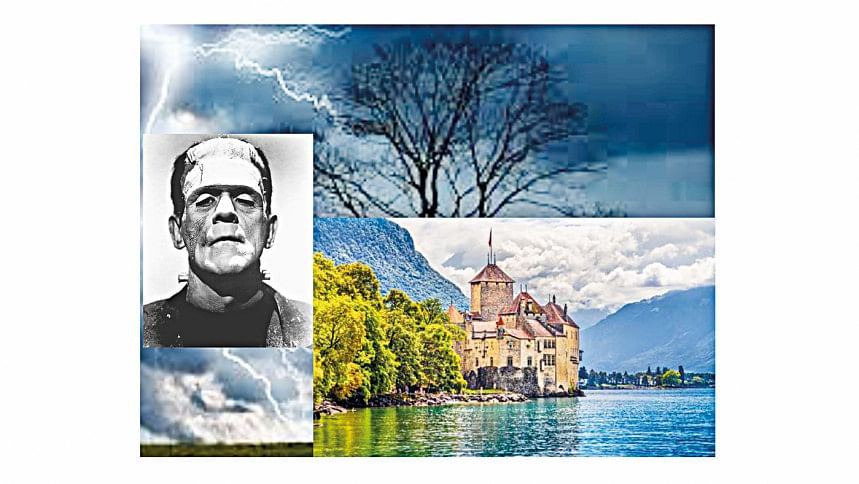

Mary Shelley's Frankenstein (1818) is well-known to the literary audience and beyond as the tale of a brilliant and mad scientist who created a horrible monster that in the end brought destruction for its creator. There have been a number of movies based on Frankenstein and his monster, not all of which adhere to the original storyline. But the theme most emphasized has surely been the Promethean spirit of Romanticism which is explored through the two principal narrators, namely, Robert Walton and Victor Frankenstein. Yet this story is also about the danger that involves in playing Prometheus, as Victor realizes after creating life from the abode of the dead. Like most Romantics of her time, Mary Shelley held a deep reverence for nature, and her Frankenstein emphasizes the importance of maintaining a balance between nature and humanity. The novel explores devastating aspects of nature when its boundaries are violated and unnatural rites are practiced..

Most of the time, Frankenstein's attitude toward nature is like a master who would like to look at the world as his possession. He turns to nature passionately after the death of his youngest brother William, "Dear mountains! my own beautiful lake! how do you welcome your wanderer?" Instead of enjoying nature as it is, earlier he dared to tamper with it, and now he wails plaintively at the natural world which is indifferent toward his misery.

The narration begins with Walton's reference to Coleridge's albatross, and the "land of mist and snow," and is foreboding of an unnatural act similar to the killing of the albatross. Coleridge's Mariner killed an innocent bird without any apparent motive, and in the process, defied human compassion regarding the value of life. Victor, on the other hand, creates a life whimsically, and thus transgresses both natural and communal boundaries.

In spite of his egocentric views of the world, Victor is not unaware of the healing power of nature. Whenever he refers to his childhood in Geneva, he remembers the beautiful mountains and green pastures surrounding his father's house. But in his narration, it also becomes clear that in his zeal of creating life, for a time, he had managed to have forgotten nature. Mesmerized by the power of nature manifested through lightning, he wanted to possess it without understanding the responsibility that is required with its handling.

As mythical Prometheus taught mankind, his own creation, the use of fire, Victor, uses the secret of electricity (another form of fire) to breathe into his monster. However, unlike Prometheus he lacks foresight, and therefore, instead of being saved by his creation, is hounded by it. By the end of his sorry tale, he becomes the identical lightning struck tree that inspired him with his scientific ventures: "But I am a blasted tree; the bolt has entered my soul; and I felt then that I should survive to exhibit, what I shall soon cease to be—a miserable spectacle of wrecked humanity, pitiable to others, and abhorrent to myself."

Anne Mellor astutely observes, "Nature pursues Victor Frankenstein with the very electricity he has stolen. Lightning, thunder, and rain rage around him. The November night on which he steals the 'spark of being,' from nature is dreary, dismal and wet."

In spite of his egocentric views of the world, Victor is not unaware of the healing power of nature. Whenever he refers to his childhood in Geneva, he remembers the beautiful mountains and green pastures surrounding his father's house.

Most of the time, Frankenstein's attitude toward nature is like a master who would like to look at the world as his possession. He turns to nature passionately after the death of his youngest brother William, "Dear mountains! my own beautiful lake! how do you welcome your wanderer?" Instead of enjoying nature as it is, earlier he dared to tamper with it, and now he wails plaintively at the natural world which is indifferent toward his misery. Reared and spoilt by the attention of his family and friends, Victor is invariably the center of his own world. His egotistical concern with himself shows itself at its extreme when he busies himself with creating the female creature in a remote Scottish island. There, while he scoffs at the wretched living condition of the islanders, his ego is pricked as they don't show him enough gratitude for taking up his abode among them. Even though hailed by Walton as a noble creature with the capacity of "elevating his soul from earth" (16), he is actually an outcast mirroring his monster. Because of his unnatural birth, the monster is unwelcomed in human society, and similarly, because of his transgression and ego-centric vision of the world, Victor is a stranger to nature.

Thus, the creator and the creation entreat the two worlds whose doors are tightly closed for them. Ironically enough, whenever Victor tries to embrace nature imploring it to sustain him, almost as an answer he finds his monstrous creation in the vicinity reminding him how usurping the powers of nature, he had created a grotesque and unnatural being. It seems that the creature itself becomes an agent of nature bringing about his retribution.

Even though she focuses much on the devastating powers of nature, Mary Shelly strikes a balance by revealing its nourishing and nurturing aspects as well. Through the characters of Henry Clerval, Elizabeth Lavenza, and Ernest Frankenstein, she elucidates this harmonious relationship between nature and human beings. Victor's wife Elizabeth appreciates and loves little things of nature as does his best friend Henry, but their unfortunate and untimely deaths complete Victor's dissociation from nature. Through the character of Ernest, Victor's other brother, Mary Shelley further emphasizes the importance of the sustaining power of nature. Not surprisingly, Ernest is the only member of Frankenstein family who survives the tragedy that overwhelms his other family members.

The aspiration and failure of Victor Frankenstein thus focus on the futility of an ambition devoid of human compassion. His failure can then be seen as his lack of understanding in the unity of the elements of the universe, of which nature is an essential part. For Victor, the creation of his creature was a scientific process of anatomy that required little understanding of nature and life. He also forgot all about ethical and aesthetic considerations.

The most celebrated idea of Romanticism is thought of as an individual experience, as the six major male Romantic poets prioritized the rise of the individual over the group. However, there are hundreds of other writers of the time, both male and female, who tells other stories behind the "romantic sublime," seeing it as more of a shared tale of mutual understanding and partnership not just between men and women, but between the solitary and the community, and keeping a balance between nature and humanity.

For many readers, Mary Shelley's Frankenstein is a tale quite relevant to the waste land of the 21st century. In our quest for achieving the unachievable, we, too, have destroyed lives, breached sacred relations, and reversed the natural order of things. Would it be too pessimistic to say that the monstrosity of our actions will get us too? Or, perhaps, we are delusional enough to think of rousing ourselves and restore the lost balance.

Sohana Manzoor is Associate Professor in the Department of English and Humanities, ULAB. She is also the Literary Editor of The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments