Democracy facing an existential struggle

In simple terms, democracy means the rule of the people. If there is a massive disparity with regards to ownership and power structure, and if class, gender, ethnic and religious discrimination dominate social relations, then the idea of the rule of the people cannot be realised. The struggle to achieve that goal is the essence of democracy.

However, the primary condition of democracy is that it should at least operate on the basis of the consent of the people – consent that is expressed through elections. Let us look at where Bangladesh is at in this regard, after 50 years of existence. The movement for democracy in Bangladesh has been going on for decades. Under Pakistani rule, the Liberation War was a result of this desire for democracy. Even after the war, the struggle continued. The fight against martial law in the late 70s and 80s was also a fight to establish democracy. In the 90s and even now, this fight has endured.

It is a matter of great misfortune, as well as of disappointment and uncertainty, that democracy in Bangladesh is practically absent now. A system of governance must depend on the people to remain accountable, transparent, and responsible. Even if the process of being accountable to the people is erroneous, it should be corrected through people's participation and elections. There is effectively no such thing in Bangladesh right now. If we look at any number of institutions, be that the administration, law enforcing agencies, universities or the judiciary, they are all suffering from a lack of transparency and public scrutiny. Corruption has become the rule of the day. All the commissions, including the Human Rights Commission and the Election Commission, have made themselves ornamental.

Public universities have now also become an extension of party rule. We have seen government appointed vice-chancellors (VCs) of different universities being accused of corruption, irregular appointments of teachers, destroying the educational environment by patronising criminals, and nurturing ruling party student organisations as hired goons to suppress dissenting voices. As a result, universities, places that are supposed to be centres of free thinking, that are supposed to harbour democratic sentiments, are now unable to establish themselves as proper institutions.

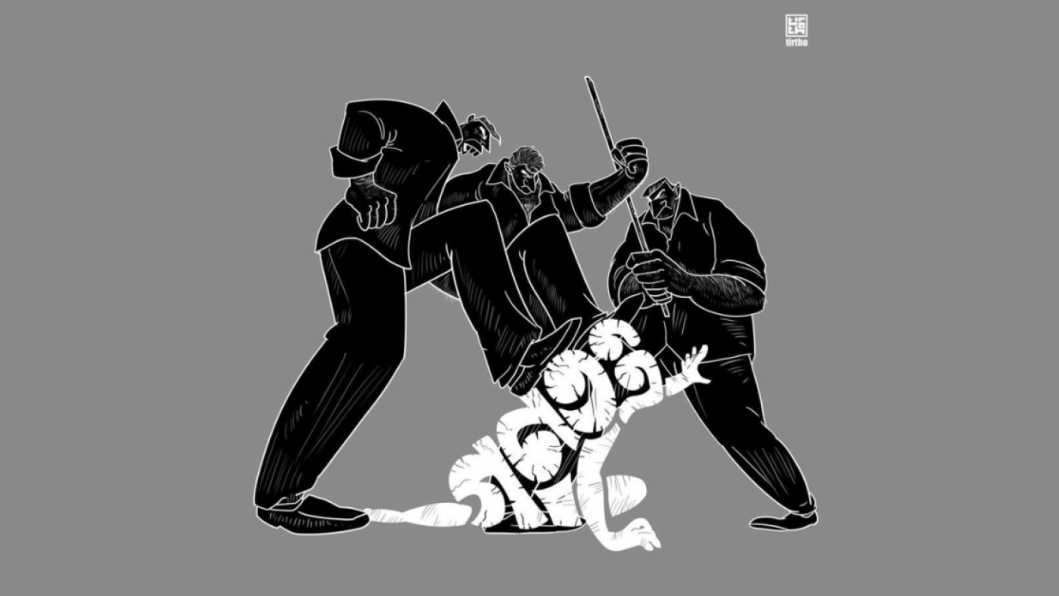

Even in society, because of the absence of democratic processes, all sorts of crimes – murder, rape, grabbing of land, waterbodies and forests, corruption – are going unchecked. It's as if anyone has a free pass as long as they are connected with the powers that be. When criminals get patronage from higher up the chain, the judiciary too becomes non-effective. On the other hand, any sort of outcry or protest against misrule and corruption is being met with force, and activists are being attacked by the police as well as ruling party goons. They are also being harassed with the use of the Digital Security Act. Enforced disappearances, torture in custody and false cases have become instruments to run the show unopposed.

Starting from the centre and going all the way to remote areas, we see a tendency of zero accountability. Corruption, robbery, defaulting on bank loans, bad deals with high commissions by powerful people, price hikes, rape and sexual harassment, grabbing properties of the poor and the marginalised people, money laundering – all of these are allowed to happen because of the absence of a democratic process.

The absence of the democratic process is also allowing the government to undertake megaprojects such as the ones in Rampal, Matarbari, Banshkhali and Rooppur, which are tremendously harmful to Bangladesh not only from an environmental standpoint but also from a financial one. From the very beginning, these projects have suffered from gross irregularities, and a lack of accountability and transparency. The consent and the participation of the people should have been the principal requirement before large projects such as these are undertaken. People should have been informed about the risks and potential issues. None of these things were done, and any voices that were raised on this issue were quickly stifled. A culture of fear was created to implement mega projects to give profits to certain local and foreign groups at the cost of the people and the environment.

If even a shred of democracy existed, the level of opposition that Rampal received from the public and the experts would have seen the project scrapped. If a shred of democracy existed, the universities would not have been in this condition where knowledge is held hostage to partisan politics. If the democratic process existed even in the slightest, the justice system would have a minimal basis to stand on. If the democratic process existed, we would have seen the people's representatives contribute in some meaningful way to society.

The condition of the youth in our country, the plight of women, and the fact that people of different ethnicities and religious identities are now even more at risk – that they are being dispossessed of their lands and attacked at a greater frequency – all comes down to the absence of a democratic process.

This is why, for people of all ethnicities, religions, classes, and ages, the struggle for a democratic process, in a personal and collective sense, has turned into a struggle for existence.

Transcribed and translated by Azmin Azran.

Anu Muhammad is a professor of economics at Jahangirnagar University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments