The Little Mermaid: Has Disney sanitised our expectations from fairytales?

Disney, a brand built on happiness and light fare, makes films that are loved by parents, children, and everyone in between. However, the polished happy endings of many of their classic films are a long way off from the original fairy tales that inspired them.

Danish author Hans Christian Andersen originally conceived The Little Mermaid in 1837, in which the mermaid searches for the man of her dreams.

In Disney's The Little Mermaid (1989), the protagonist, Ariel, is introduced as a beautiful, adventurous, smart, and kind teen with an amazing gift—her voice. Not only is she perfectly slender, naturally curious and socially superlative among the creatures of the sea, she is the king's daughter—a princess with social stature. Although the film is beloved, I have always felt uncomfortable with its central message.

As we find out, Ariel desires to become a human being. She consistently questions her environment, her body, and her happiness, envying folks on the land, until she gets what she wants: a man.

To achieve her dreams, she makes a deal with the sea witch Ursula, giving up her special voice to be part of a society that would not normally accept her in her true form.

The handsome and confident Prince Eric falls in love with Ariel, who has never spoken a word in his presence. The moral of the story lies here: change who you are—not simply to be loved, but also to be accepted by others. Additionally, it portrays men as physically judgmental, only caring about the way women look, and not considering their thoughts or feelings.

I am in favour of Ariel evolving from a girl to a woman and discovering her identity, but I don't feel comfortable when influential characters suddenly cast away their unique and admirable qualities for acceptance.

The bargain between the nameless mermaid and sea witch in Andersen's version is more costly: the mermaid has her tongue cut off, and every human step she takes is as painful as standing on knives. She also never gets the prince because he marries someone else.

She strikes another deal with the sea witch to kill the prince, but she can't carry it out—so she commits suicide instead. Her body dissolves into foam, but instead of ceasing to exist, she feels the warm sun and discovers that she has turned into a luminous and ethereal earthbound spirit, a daughter of the air. Because of her selflessness, she is given the chance to earn her own soul by doing good deeds for mankind for 300 years, and will one day rise up into heaven.

In the Disney film, Ariel has to go through no great lengths to gain the love and acceptance of the prince, unlike Andersen's mermaid.

The author presents the more realistic message: despite how great of a sacrifice or outward change is made, we can never fundamentally change the essence of who we are, and can never find true acceptance and happiness in the altered form.

In contrast, the movie portrays a more censored moral: we are able to achieve true happiness and acceptance by undergoing extreme change for the ones we love. Through minor sacrifice and patience, eventually, we will gain the love and respect of those we changed for.

While Andersen's moral seems more negative and darker than the film's, the truth and realism behind it make it a much more thoughtful message.

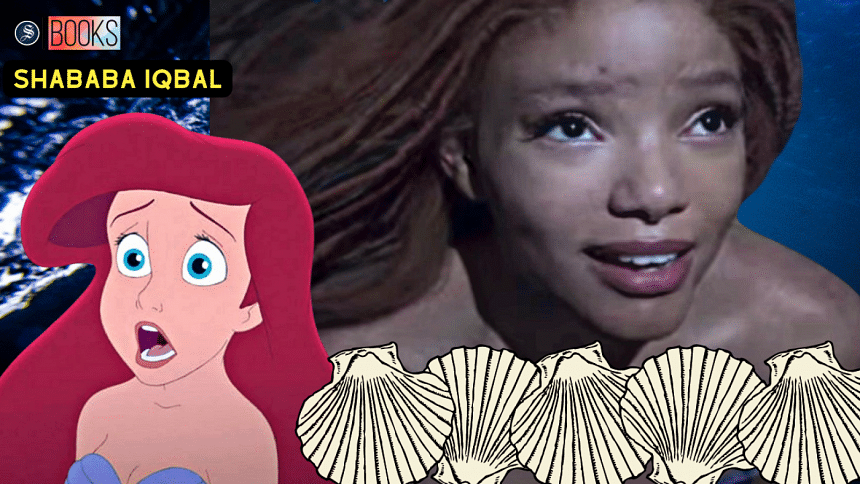

In 2023, Disney will have another go at The Little Mermaid, with a live-action remake starring African-American actress and singer Halle Bailey as Ariel and British actor Jonah Hauer-King as Prince Eric.

Disney's sanitised animated version, with its focus on a beautiful princess and a happy ending, removes much of the complexity and most of the unsettling elements of Andersen's tale. There are gory details from the original story that young children are too vulnerable to be exposed to, but the notion that we should shield children from dark fairytales is hypocritical. The honest way would be to tell them violence does occur. The world is filled with struggle and conflict. We have yet to see if 2023's The Little Mermaid will explore the dark origins of the story, but if it does, it is sure to set itself apart in the growing list of Disney's self-adaptations.

Furthermore, Disney has made us comfortable with fairytales being about how things "look", rather than respecting their nuances.

Andersen's mermaid is described as having "skin as clear and delicate as a rose-leaf, and eyes as blue as the deepest sea".

When Ariel first splashed into movie theatres over 30 years ago, she had a distinctive look. Enormous blue eyes dominated a porcelain-skinned face framed by bright red hair. Her only article of clothing was a purple bikini top made of seashells, and instead of legs, she sported a light green fish tail.

For decades, Disney only considered white characters as worthy of inclusion in their stories. It was not until the 90s that they began to introduce non-white protagonists, including Pocahontas, Mulan, Jasmine in Aladdin (1992), and Esmeralda in The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1996). And it was not until 2009 that Disney introduced a Black princess to the canon, with Tiana in The Princess and the Frog.

On September 10, 2022, we got our first teaser of Halle Bailey's Ariel, adorned with her mermaid's tail, purple bikini top, and ginger dreadlocks. We also heard her sing some of the character's signature song, Part of Your World, and got a glimpse of the underwater kingdom that Ariel so longs to escape. For most, it was a joy. Bailey—one half of the singing sister duo Chloe x Halle—looked radiant as the wistful mermaid, while her sweet vocals introduced a fresh take on the character. But unfortunately, the teaser also resulted in a revival of the racist remarks that cropped up when Bailey was first cast.

Tied to the idea that the live-action version of Ariel should reflect her original appearance, naysayers declared that Bailey was #NotMyAriel. Many claimed that her casting was an example of "woke" culture gone amok.

The outrage is profoundly unreasonable. I cannot stress this emphatically enough, mermaids don't actually exist. They are the product of Andersen's dark imagination, and we need to open up to creativity in reinterpretations of stories about mythical characters.

Throughout history, white people have been overwhelmingly represented in every pillar of popular culture. From television to film to broadcasting, no racial demographic has ever been more catered to than white people. Thanks to 2023's The Little Mermaid, Black and brown girls can finally see themselves as princesses in a film where the protagonist's skin colour is not as instrumental to the story as the princesses' heritage was in Aladdin, Mulan, and The Princess and the Frog, making that choice all the more relevant and potentially influential. As a genre, fantasy can offer more diversity because of its particularly imaginative nature, but the recurring and vocal oppositions to it indicate racist viewpoints, rather than a presumed attachment to a faithful adaptation.

Shababa Iqbal is a Journalism graduate from Independent University, Bangladesh, who likes Jane Austen's novels and Disney movies. Email: [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments