‘Higher education is slave-generating’

So remarked a university student in a recent interview on his academic experience. Specifically, he stated, "Most of our national wealth is in the hands of a few people... this [education] system just builds modern slaves who will dedicate their lives to make someone else rich, while believing they are making career progress. Actually, this slave-generating system is not for 99 percent of the people. This is not an education system at all." Facts aside, the sentiment itself speaks volumes.

With the economy of Bangladesh growing strongly in recent decades, creating an exploding demand for education, enrolment has grown commensurately. Yet, the "outcomes" of education have been intriguing. The nation produces uncounted Golden-GPA-5-holders, and pass rates in public exams soar off the charts. But when these students come to universities, a large number of them are unable to write a decent sentence or solve a problem they have not memorised.

University graduates, too, have consistently failed to meet the standards demanded by local employers. Their education is indeed baffling both to the employers and hapless parents straddled with high expenses and unemployed progeny with a certificate in hand worth only the paper on which it is printed.

The general opinion is that the overall education quality has been consistently deteriorating. The vice-chancellor of a prominent private university lamented that university graduates struggled in the job market as they had to compete with foreigners. And why are foreigners being hired? Because Bangladesh's educational institutions "lag behind in providing relevant skill-oriented education."

Globally, these graduates have even less chance of succeeding (with few exceptions). And the remittances on which the nation depends come from physical labour, not higher-level cognitive skills of expatriates. Over the years, the misalignment between academia's graduates and employer needs has only intensified.

According to one multilateral agency, "Unemployment rates are consistently high among tertiary graduates." That matters have really gone askew is reflected in the words of a Trustee Board member of a reputed private university, who was asked whether his company would hire his own university's graduates. His categorical response was, "No!" The reason? "I cannot use them."

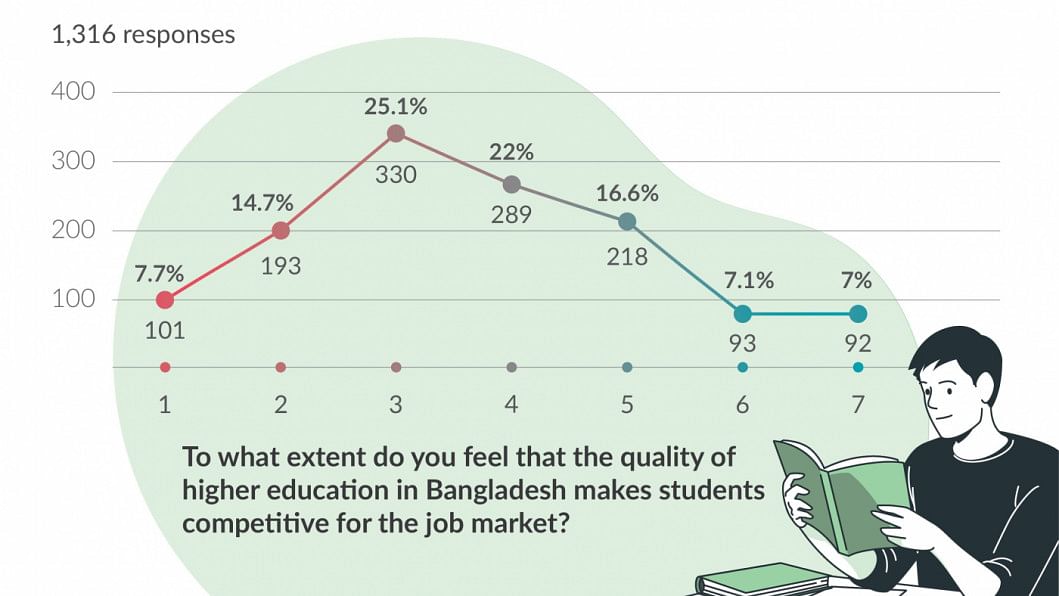

For Bangladesh, it is imperative for educational institutions to combine the nurturing of intellectual growth with new (4IR) skills necessary to navigate a globalised world. Studies confirm that employment prospects are the second most important factor students expect from their academic institutions. To understand how students feel about their educational experience in Bangladesh in the premier academic institutions, our study asked, "To what extent do you feel that the quality of education in Bangladesh makes students competitive for the job market?" A total of 1,316 students responded (see the graph where 1=very little; 7=very much).

The findings are unsurprising: only 14.1 percent felt the education they received was making them competitive. Many lacked any exuberance about their academic institutions which was seen as good, average, it's alright, or not so good-not so terrible. A number of respondents went further to comment on their disappointments. A few are shared here for the record.

Student 1: "Poor quality. [Some] faculty members are amazing, but the others are simply not. One teacher commented, 'This is a government job; your evaluation will not cause me any problems.' Most teachers lack empathy… students are even afraid to ask questions. The courses are outdated and redundant courses are taught."

Student 2: "There's a large discrepancy between the level of education we get and the level that is advertised. The university degree doesn't relate to the actual education being provided… Degrees are losing their value, unable to provide skills. We need a skill-based education system."

Student 3: "Not bad. However, many subjects are taught by teachers who lack in-depth knowledge of their subjects. Naturally, they teach badly. Students can earn grades by studying strategically. However, there are also teachers who really want to provide better [understanding] of the subjects taught. The internet has it all, but this is the precise reason to have guides to show the way in this ocean of information."

Student 4: "I don't know why I was present in the class; boredom was at its peak; teacher was not prepared for the class, as am I now. No new induction was provided regarding the present technology; lectures were copied from foreign books; quality of teaching is poor at times. Many teachers are toppers of their batches, but they cannot teach. After the first week, most students are lost in a black hole."

The above comments mostly concern the elite institutions in the country. It behooves the educational authorities (the education ministry and the University Grants Commission) to delve into what goes on in the other academic institutions that have mushroomed in the last decade. In the 51 years since independence, not a single academic institution has made it into decent global rankings. Over USD 5-10 billion are repatriated each year by foreign workers occupying the middle and upper tiers of the job market.

Industry bosses will not hire products of academe, and parents are seeking to send their children overseas for their education. How does this situation square with Bangladesh as an aspiring middle-income country?

The vision for higher education is a laudable one (Strategic Plan 2018-2030): "Our universities should be true centres of excellence where, along with acquiring knowledge, skills and competence of the highest level, students will practise democratic norms and cultural values and will be conversant with economic development issues." The facts on the ground are starkly different. The challenge is to translate this vision into reality, to convert the uncertainty our graduates experience into stable jobs, to wipe away the worry beads of parents who despair about leaving their children and grandchildren behind in uncertainty and deprivation.

It is time to hold the education industry accountable. Administrators must build programmes that develop marketable qualities in their students. Teachers must provide the intellectual energy to strengthen students' knowledge base and build human capital. And the government must provide targeted financial and other resources while holding the education industry answerable. It is time the education industry, the nation's backbone, was run competently, undergirded by a moral and ethical foundation to take the nation forward.

Dr Syed Saad Andaleeb is distinguished professor emeritus at Pennsylvania State University in the US, former faculty member of the IBA, Dhaka University, and former vice-chancellor of Brac University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments