The sorry state of rivers in Bangladesh

The World River Day, which was observed on Sunday, is nowhere more relevant than in Bangladesh, which is known as a nodimatrik desh – a country borne by rivers. Most of Bangladesh lies on the Bengal Delta, which was created by the sediment deposited by rivers flowing down from the Himalayan and the Arakan mountain ranges. There used to be more than a thousand rivers crisscrossing through Bangladesh. Many of those rivers are now lost, mostly due to human interventions. However, according to the Bangladesh Water Development Board (BWDB), the country still has about 230 rivers with perennial flows and between 310 and 405 rivers have flows only during the summer.

Rivers have major roles in the ecology and economy of Bangladesh, one of which is serving as a means of transportation. Traditionally, waterways used to be the main method of transportation; all major cities of Bangladesh developed along riverbanks and, more prominently, at river crossings. Transportation using rivers is usually cheaper and less polluting. Unfortunately, transportation via rivers has declined over time. In contrast to the information provided by the BWDB above, the Bangladesh Inland Water Transport Authority (BIWTA) claims that the country has 700 rivers with waterways totalling 13,000km in length. Of this, 5,968km is classified for navigation, of which 3,865km is classified for navigation during the dry season. It also classifies the waterways into four groups – namely trunk routes, link routes, secondary routes, and seasonal routes. The wide divergence between BWDB and BIWTA regarding the total number of rivers reflects the paucity of accurate information. This is indeed lamentable in view of the crucial importance of rivers for Bangladesh.

Be that as it may, it is clear that the length of navigable parts of the rivers has shrunk over time. The process started with the construction of railways by the British rulers in the 19th century. It affected the rivers and waterways in two ways. First, railways provided a faster way of travel and transportation of goods, hence reducing the importance of waterways. Second, the railways represented the first wave of interventions in the floodplains in Bangladesh, obstructing the free flow of water on them. These obstructions started the process of separation of the floodplains from river channels, triggering the gradual decay of both the river channels and the floodplains.

The importance of waterways declined further when the country embarked on the construction of roads and highways, particularly after independence. Besides the main arteries, a huge network of rural roads has been constructed in recent decades as well. According to news reports, more than 11,000km of roads have been constructed in Sylhet and Sunamganj districts alone. Of course, road connections are necessary for villages. However, in most cases, these roads have been built in an indiscriminate and unplanned manner, with no regard for optimisation and minimisation of water flow obstruction across floodplains. In particular, the necessary principle of constructing roads in elevated form in active floodplains and haor areas was not observed.

Third, the Cordon approach to rivers that Bangladesh has followed since the 1950s has done irreparable damage to its rivers and floodplains. This approach encourages cordoning off floodplains from river channels by constructing embankments. As a result, rivers become disconnected, waterways shrink, and both floodplains and river channels suffer. Railways and unplanned roads and highways also serve as embankments, aggravating the negative effects of the Cordon approach.

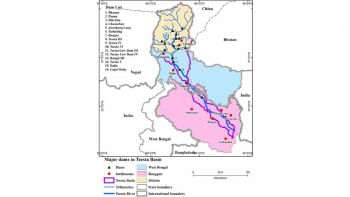

Fourth, a major reason for the decay of rivers and waterways since the 1970s is the interventions in the shared rivers carried out by the upstream countries, particularly India. The most prominent examples are the Farakka and Gajoldoba barrages, which divert the dry season flows of the Ganges and Teesta rivers, respectively. As a result, most of the rivers in southwest and northwest Bangladesh are dying. India's dams and barrages are causing harmful morphological changes in Bangladesh's rivers. With little water in winter, the river beds dry up and get compacted. As a result, when India opens all the floodgates in summer, the rivers cannot do enough bed-scouring to accommodate the water and instead expand sideways through bank erosion. The rivers are therefore becoming shallower and wider.

Ironically, while damaging the health of Bangladesh's rivers through its interventions, India at the same time is eager to have river transportation through Bangladesh to its seven northeastern states. For this purpose, it is persuading Bangladesh to carry out dredging of a narrow part (often only 40 feet wide) of Bangladesh's river channels so that Indian cargo vessels can travel to its northeastern states. Unfortunately, such narrow dredging is deforming the riverbed configuration further, because the dredged material is deposited on the adjacent portions of the riverbeds. It is necessary for India to realise that, for sustainable river transportation through Bangladesh, it is necessary to restore the health of its rivers. Thus, it is in India's own interest to remove all dams and barrages on the upstream reaches of the shared rivers and their tributaries.

It may be noted that Article 7 of the 1997 United Nations Convention on the Law of Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses clearly forbids upper riparian countries from carrying out any interventions in the shared rivers that may cause "significant harm" to lower riparian countries. In explaining this rule, Article 6 of the convention notes that disruptions by upstream countries of the "existing uses" of international watercourses in downstream countries would be considered as significant harm. Needless to say, the economy and life of Bangladesh have evolved over thousands of years on the basis of the uninterrupted flows of the transboundary rivers. Diversion and impounding of these flows are therefore forbidden under the UN convention. Bangladesh needs to sign this convention without any further delay and urge India and other South Asian countries to sign it, too, so that they could use it as an internationally agreed code of conduct regarding the shared rivers.

Unfortunately, the Bangladesh authorities fail to see the win-win solution that the Open approach offers. Instead, they tenaciously cling to the Cordon approach, most likely because of the large budgets involved with embankment and other construction projects that this approach generates. Bangladesh is also failing to negotiate river issues with India from a position of strength. Instead of using the UN convention on using international watercourses and the advantages it has regarding transit, transshipment, port use, etc to establish its rightful claims on the shared rivers, Bangladesh is giving up these rights. Instead of preventing India from construction of upstream river-intervening structures without its consent, Bangladesh is now seeking permission from India for the go-ahead for a minor river use project within its own territory, as the recent Kushiara Agreement illustrates. So, the question is: When will the authorities stand up for the rivers of Bangladesh?

Dr S Nazrul Islam is the founder of Bangladesh Environment Network (BEN) and the initiator of Bangladesh Poribesh Andolon (BAPA). He is the author of Water Development in Bangladesh: Past Present & Future.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments