Alliances with smaller parties: A game of numbers

Every region in the world has its own brand of politics. While there may be some interregional commonalities, it is always the uncommon factors that define the politics of a particular region. For example, one of the key characteristics of South Asian politics is the tendency to form alliances before a major election. While occasionally the allies may have strong ideological similarities, in most cases, the partnerships are held with loose, common threads.

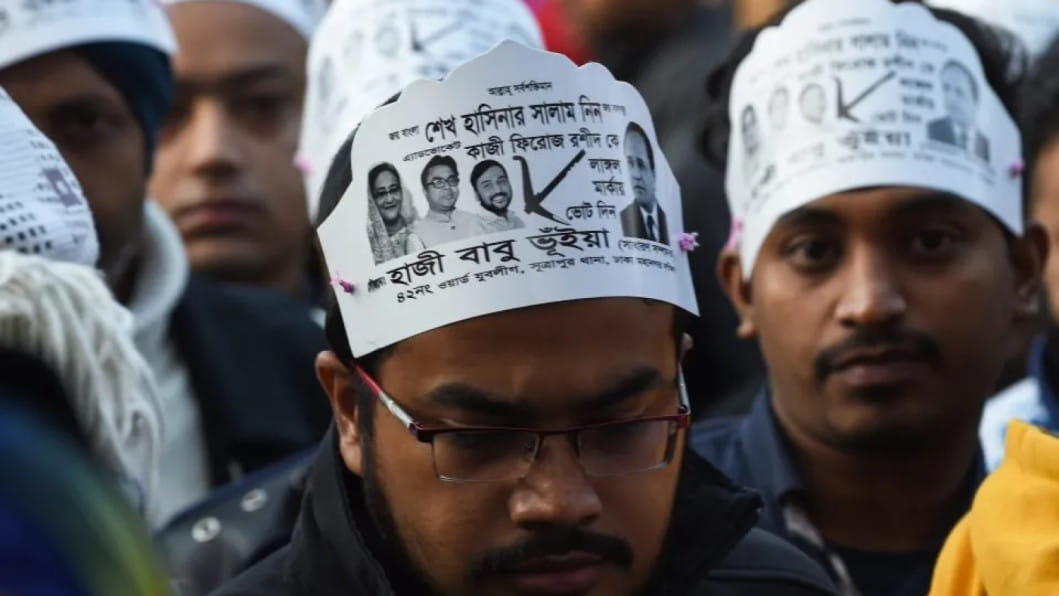

Bangladesh, being a part of South Asia, is no different. With the next parliamentary election set to be held in a year or so, the ruling Awami League and the BNP, the two dominant political forces in the country, have once again started rallying lesser and sometimes even completely unknown political parties to form alliances.

Eventually, it's all about numbers. Before the 2001 general election, the then main opposition in parliament, BNP, formed a four-party alliance with three other like-minded right-wing parties, including Jamaat-e-Islami. BNP and its allies swept that election with a two-third majority and ended up forming a coalition government. Before the following election in 2008, the Awami League took a page out of their archrival's books and formed a bigger alliance with 14 like-minded parties, who were mostly left and centre-left in terms of political ideology. That coalition later came to be known as the "grand alliance" and it ended up winning an even bigger majority in parliament than what the four-party alliance did in 2001.

After a disastrous defeat in the 2008 election, the BNP took a couple of years to regroup and decided to form an even bigger alliance, this time with as many as 19 parties, in 2012. Apart from Jamaat-e-Islami, the remaining 18 parties were either one-man shows or existed only on papers and signboards, let alone having any significant vote bank.

Around the same time, the ruling Awami League revived the long-pending 1971 war crimes trial against top leaders of Jamaat-e-Islami. By the time the next general election rolled around in 2014, some of the top Jamaat leaders had already been executed for their war crimes, and some others, alongside a number of BNP stalwarts, were awaiting the same fate, which significantly curtailed the impact that the 20-party alliance could have had.

The BNP-led alliance tried to retaliate by launching violent protests, aiming for two objectives: 1) to somehow prevent the execution of the Jamaat and BNP leaders; and 2) to prevent the Awami League from holding one-sided elections. None of those objectives were achieved, and the BNP-led alliance only drew fierce criticisms from both home and abroad for their bloody means. Since then, Jamaat has been stripped off their right to participate in elections, and the 20-party alliance nosedived into the ground.

If we analyse the results of some of these elections, we will see that only about a few parties actually have vote banks big enough to have any impact on the overall outcomes. Some of the other, lesser known parties have even been known to have given up their own symbols and chose to run with the symbols of the dominant parties in the alliance. Some of them have even won in elections as well because they received votes from the dominant parties' supporters due to their association with the alliance.

In the ninth parliamentary election in 2008, a total of 38 parties took part. One of those parties had the organisational strength to nominate a candidate for just one seat in parliament, and there, too, that candidate managed to bag 297 votes only. In 2014, at least five among the 12 parties who took part in the election received less than 10,000 votes combined. In some cases, the smaller parties were the ones who were the beneficiaries. For example, Jatiya Samajtantrik Dal, Workers Party, and Bangladesh Tarikat Federation contested in the election with the Awami League's "boat" symbol in the 2014 election and bagged only 1.75 percent, 2.06 percent and 0.3 percent votes, respectively. But the alliance head, Awami League, accommodated their leaders in the cabinet and some of them became ministers as well, which, quite understandably, they would have never been able to achieve had they contested on their own.

However, as the 12th parliamentary election draws nearer, we are observing an incredible reversal of the trend. While some smaller left-wing parties have started to side with the BNP, which has always been centre-right, some right-wing parties are getting closer to the Awami League, which has been historically centre-left. It is going to be quite hard to tell what this would eventually transpire to, simply because this has never happened before in Bangladesh.

Alliances are a tested strategy to win elections all over the world. However, alliances between parties with completely opposite standings are not very common, and it is hard to tell how well party members at the grassroots level would gel given their ideological differences, especially during election campaigns. Probably, only time will tell.

Mohammad Al-Masum Molla is deputy chief reporter at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments