In Memory of Jibanananda Das

Darkling I listen; and, for many a time

I have been half in love with easeful Death,

Call'd him soft names in many a mused rhyme,

To take into the air my quiet breath

Now more than ever seems it rich to die

To cease upon the midnight with no pain

John Keats, "Ode to a Nightingale"

Indeed, Jibanananda was the most death-haunted of poets. At almost every stage of his poetic career, we find him contemplating life at its terminus.

Half in Love with Easeful Death

By 1954 Jibanananda Das, after years of neglect, was beginning to gain increasing attention as a poet all over Bengal—East or West—and had a steady teaching job after a long, long time. Indeed, in 1953 he had been awarded the Rabindra-Smriti Puroshkar for his book of verse, Banalata Sen. In May, 1954 his Jibanananda Dasher Shreshto Kobita came out from a reasonably good publishing house, collecting his best poems.

On 13 October, Jibanananda read out a poem in a gathering of poets organized by Calcutta Radio. Something of a flaneur, he went out for a walk on 14 October. Acquaintances knew him as someone who often walked in a kind of trance. Is that why he was hit by a tram at an intersection of Calcutta's Rashbehari Avenue? The impact left him sprawling on the street. The battered poet was taken to a nearby hospital by people there. At the news, his admirers—old and new—as well as family members flocked to the hospital. Some younger poets kept a vigil over the badly hurt poet. Suffering excruciating pain in a delirium-like state, he died on 22nd October at 11:35 pm.

In Keats's "Ode to a Nightingale," the English poet contrasts himself sadly, "half in love with easeful death," with the bird, "Thou was not born for death, immortal bird/No hungry generation tread thee down." A late romantic and early modern Bengali poet, Das evokes the English bard intertextually in his beautiful poem, "Shindhu Sarosh" ("The Sea Stork") when we find him contrasting the bird, which has the option of flight, to human beings, "whose bid to grasp rainbows dissipate in the fog of wintry and short-lived Hemonto days" (always, I will be quoting the poet's lines from my English translations in Jibanananda Das: Selected Poems).

A late romantic and early modern Bengali poet, Das evokes the English bard intertextually in his beautiful poem, "Shindhu Sarosh" ("The Sea Stork") when we find him contrasting the bird, which has the option of flight, to human beings, "whose bid to grasp rainbows dissipate in the fog of wintry and short-lived Hemonto days" (always, I will be quoting the poet's lines from my English translations in Jibanananda Das: Selected Poems).

Not that Jibanananda always saw the fate of birds/animals so positively. He has also written moving poems about human cruelty that led to their deaths. His poem "Campe," for instance, depicts with sadness a doe calling for its mates, who had been shot, living the poet with the thought that "we are like those dead stags lying in the spring moonlight." In fact, human callousness and murderous instincts to kill other beings—in flesh or in spirit—always haunted the poet. Consider thus "If I Were," a poem where he imagines himself and his loved ones as geese vulnerable to hunters and their guns, dying, but seeing even this as relief of sorts, since "we would no longer have to face death in small doses as we do daily in our lives." Or read "Pather Kinare," a posthumously published poem, where the poet sees a cat gasping for death in a roadside and wonders about an unfeeling world that is ignoring the animal's death travails. The poet, however, is transfixed. Soon the cat "invaded my poem with its lonely amazing white and black spots/Told me: 'this will be the utmost claim I will ever make on you.'" Was Jibanananda somehow anticipating the vigil of the poets attending him at his death in a Calcutta hospital, the empathy of his well-wishers then, and the verse tributes afterwards?

Indeed, Jibanananda was the most death-haunted of poets. At almost every stage of his poetic career, we find him contemplating life at its terminus. Thus in "Mritur Aage," he depicts a wintry, creature-bereft gray landscape of "fading light" and crows that "fly into the fog." The poet of "Andhakar" contemplates darkness as preferable to the pangs suffered in life since "you can't disturb the deep sleep of death/you aren't burning streaming pain." Relief then is hoping that there will be waking up after death and the possibility of wandering through space and time to vanished civilizations then. Thus in "Path Hata," the flaneur-poet is in a Calcutta street where "yellowish withered leaves fly by," making him go back in time. After all, "In Babylon streets too alone at night thus had I walked. /I know not why though thousands of feverish years have passed." Was it on some such occasion that he had glimpsed Banalata Sen?

For sure death spurred Jibanananda's imagination time and again and led him to great poetry. Perhaps his most memorable poem about death as a possession is "Aat Bacchar Ager Ekdin," which takes the reader to a corpse in a morgue. On the one hand, the poet sees a man who had had an overwhelming death wish realized; he would "not face anymore the stress/The heavy burden—The deep unceasing pain of consciousness". But on the other, the poet presents an owl, a frog and mosquitos "impelled by their lust for life to stay awake." A poetic realization of what Sigmund Freud had termed Thanatos and what had led to the poet ultimately becoming a morgue denizen "free of weariness?"

However, in "1946-47," a great poem written by Jibanananda on the partition riots, he laments the mass killings resulting from religious hatred fanned by politicians. In it, the poet laments the senselessness of such murderous actions and writes positively of the life force. Forever and forever, "man continues to move on even now/From blinding despair to pleasing darkness/From total darkness to festivities."

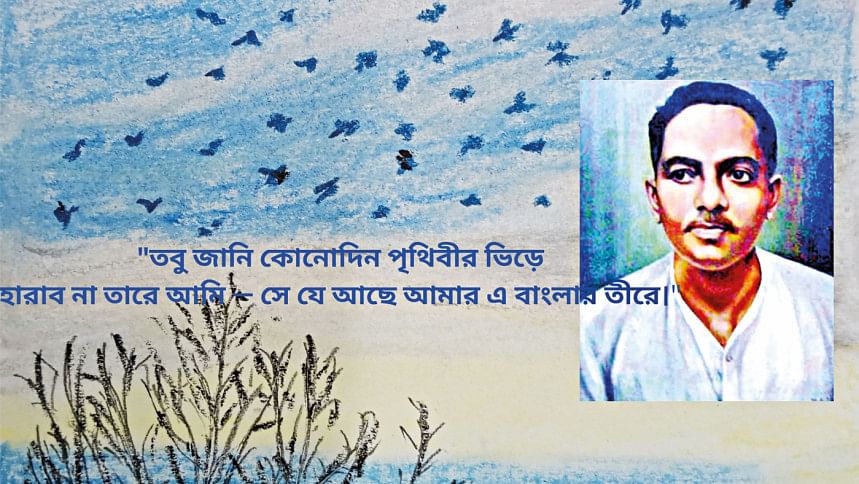

As the poet's admirers knew then and know now, Jibanananda hated having to leave Barishal's beautiful riverscapes and become part of cityscapes, like the parts of Calcutta where he would spend his last years, or even Delhi, where he had once been a teacher of English in a college for a few months. More than anything, he felt on such occasions, he would like to go back to the beloved banks of Bangladeshi rivers and be one with the flora and fauna there and its people in some form or the other. In the 1930s he composed the sonnet sequence of his posthumously published, but destined to be a classic of Bangla poetry, Ruposhi Bangla. In one of his sonnets, "Tomra Jekhane Sadh," he tells his readers they could "go wherever you desire" but he would "remain alongside Bengal's banks," for people may be mortal there too but the landscape was eternally available to the poet through his imaginative homecomings. And in perhaps the most famous of them, "Abar Ashibo Phire" he declares, "I'll come lovingly again to Bengal's rivers, fields, farmlands, /To the green wistful shores of Bengal lapped by Jalangi's waves."

He Became His Admirers

But for him it was his last afternoon as himself,

An afternoon of nurses and rumors;

The provinces of his body revolted,

The squares of his mind were empty,

Silence invaded the suburbs,

The current of his feeling failed; he became his admirers

W. H. Auden, "In Memory of W. B. Yeats"

The literary world of Bengal—east or west—mourned the unique poet's untimely and tragic death in the Calcutta hospital on October 22, 1954. His reputation though kept growing; he would soon be recognized as the greatest modern poet of this part of the world. Subsequently, trunks full of his books were discovered; whole unpublished book manuscripts like Ruposhi Bangla whole novels too! A young man named Bhumendra Guha, a poet as well as a man destined to be an eminent physician who was in the group of admirers keeping vigil in the Calcutta hospital as Jibanananda lay dying, took it upon himself to publish definitive texts of the poet he admired so. An American scholar called Clinton B. Seely, once a Peace Corps volunteer in Barishal, soon ventured to introduce the poet to the world through an excellent biography containing very likable translations of the poems. In Bangladesh, the major poet Abdul Mannan Syed published a superb selection of Jibanananda's poems and wrote about him sensitively.

Jibanananda Das now has become his admirers and lives on amongst us; his legion of devotees keeps increasing. This is as it should be. I only wish we in Bangladesh, especially people in Barishal, would do more to preserve for future generations his memories, for surely no one ever will be able to write about that part of our country with such feeling ever again. In death, if not in life, he surely has become us!

Fakrul Alam is Supernumerary Professor of English at the University of Bangladesh and is the author of a selection of translated poems titled Jibanananda Das: Selected Poems (Dhaka: UPL Books, 2nd edition, 2003)

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments