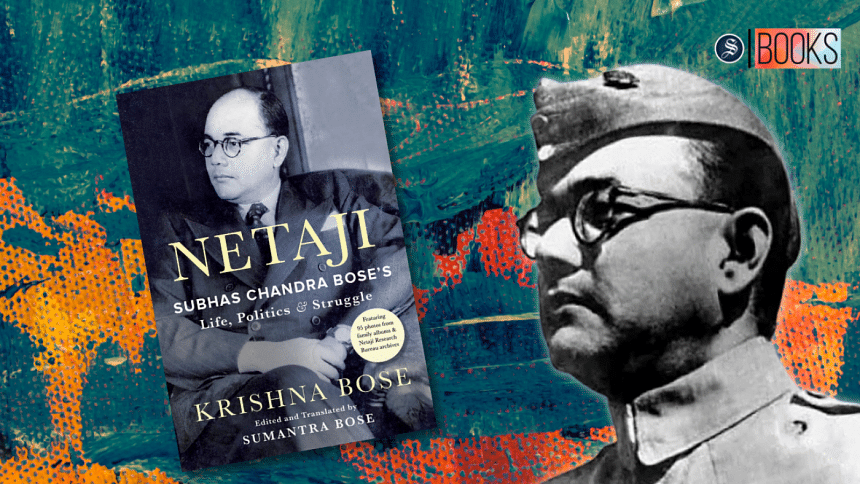

Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose: A relative’s perspective on an enigmatic hero

Subhas Chandra Bose was a leader enough, a warrior enough, and mysterious enough to warrant a look-in by serious writers of political history as well as other areas of study. And, not much surprisingly considering his activities and often clandestine lifestyle, he was in an airplane crash in August 1945 in Taipei, Taiwan's capital, presumed dead as his body was never recovered. This skeletal account has been filled up by several historians and other writers, including the book under review, which garners special attention since it was written by a prominent member of Netaji Subhas Bose's family, and a pioneering Netaji researcher, Krishna Bose.

Krishna, now deceased, was married to Subhas Bose's nephew, Sisir Kumar Bose, who was a son of Netaji's older brother, Sarat Bose. And she took it upon herself to try and unravel the life of a complex person. In the process of carrying out her endeavour of searching and recording, Krishna "discovered that Subhas Chandra Bose is much more than a romantic hero, or a swashbuckling action figure." Her work was then edited and translated by her son Sumantra, who, in the Introduction, hopes "that this compilation of Krishna Bose's lifetime of work on Netaji and his struggle for India's freedom will enlighten Indians, and especially the young people of India, about Netaji's ideals and his vision of what free India should be." Thus far, all in the family.

And, soon enough, enters Netaji in the limelight and a whole world of fascinating activities are brought to light, or are unable to come out of deep darkness, or are left wallowing in murky light by Krishna Bose. Subhas Bose comes out as an intriguing personality who, if only through one act, showed himself to be a patriot looking to free India from the British Raj, but also one who sought ways to better the existential condition of his countrymen and women. In those days of prestige symbols (very much extant in various global societies), he forsook probably the most prized one: that of resigning from the generally much coveted and celebrated career in the Indian Civil Service (ICS) in order to concentrate on freeing India from the shackles of colonialism.

Subhas Bose then entered, unwittingly or knowingly, into the world of geopolitics, a cynical reality for any nation willing to expand on its global or regional power position and then willing to employ the cynical tools required to pursue it. In a nutshell, he was willing to shake hands with the metaphorical devils, and subsequently did so, with Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany, in order to help get rid of another, the British colonial power, from his beloved homeland.

As the book posits, that was not a hard thing for him to do. His determination to free his homeland from the shackles of colonialism made him turn his attention to another Axis power, Japan, in a combined effort to, from his perspective, serve his own interest of bringing an end to colonialism in the Indian subcontinent.

The author describes in generally extensive detail the calculations, intrigues, and modus operandi of Bose carrying out his plans with important assistance from a group of loyal followers, but one could feel that Krishna Bose might have held back on identifying some of the warts that hindered Netaji from achieving his multifarious goals. Eventually, though, the breadth of the war and the changing of power positions of the major players succeeded in helping India gain its freedom from British colonialism, though not in the shape of what Bose had envisaged for his homeland. Bose was dead before August 14, 1947 came about.

Krishna Bose does provide a fairly extensive account of Netaji's family tree, including her own connection with it, and singles out the influence and care given to the family, especially Subhas, by Basanti Debi, the widow of another legendary nationalist leader from Bengal, Deshbandhu Chittaranjan Das. However, she refused to "play the political role Subhas desired of her." Clearly politics was in Bose's inherent makeup and he could not be away from it for too long, if ever.

We also learn of his softer side, of the family man Subhas, of his wife, Emilie Schenkl who once told Krishna Bose, "India is my first love and only love." Krishna avers that although she was very influenced by him, Schenkl does not seem to have influenced Bose politically. ACN Nambiar, Netaji's closest and most serious associate in Europe had this to say about him: "He was a one-idea man, a one-idea man you can sum up—singly for the independence of India." But he also goes on to say: "I think the only departure, if one might use the word departure, was his love for Miss Schenkl…."

The book contains its fair share of accounts of Netaji's relationships with Indian and global leaders and eminent personalities, specifically Jawaharlal Nehru, Rabindranath Tagore, Adolf Hitler, and Eamon de Valera. "The contrast of the formative years of Nehru and Bose," the author writes, "is truly striking." While the young Bose even at that age was tormented by his country's sorrowful plight, for the young Nehru, there was no such sense of mission. In fact, and this is very educative of that contrast, at the Tripuri session of the 1939 Indian National Congress, Bose wrote that no one had done more harm to him personally and to their cause than Pandit Nehru during the war. When rumours reached India that Bose was coming with the victorious Japanese, "Nehru declared that he would be the first person to meet him with a drawn sword."

Krishna Bose assesses: "Nehru tended to idealism and Bose to realism. Nehru was revolted by Nazism and the persecution of Europe's Jews. Bose…felt that the Indian struggle for freedom should override all other considerations…." Regarding Gandhi, she states, "Nehru had a practically unconditional allegiance to Gandhi and Gandhi exercised a hypnotic power over him. But Bose, whilst deeply respectful of Gandhi, was not as mesmerized." Bose really was the best suited of the Indian leaders to play the geopolitical game.

That geopolitical angle becomes apparent when the author studies the relationship between Bose and Hitler who did meet each other in the Berlin Reich Chancellery in May 1942. In the author's words: "It can be said…that Netaji's flexible and pragmatic foreign policy in the pursuit of India's freedom ran into something of a brick wall with the Nazi German state and especially its leader. Ironically, in light of Hitler's flat rejection of a declaration supporting Indian independence in 1942, when Netaji proclaimed the…Provisional Government of Free India in Singapore on 21 October 1943, Hitler's Germany was one of the nine recognizing governments."

The author also brings up several close and dedicated associates of Netaji and we note that they comprised Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists, Punjabis, Pathans and representatives from all over British India. Several battles fought against the British by Indians, Japanese and other foes of the empire in Asia are analysed from different perspectives with the general theme of the dedication and patriotism of Subhas Bose.

There are imponderables: Bose's mysterious death has not been totally and unequivocally explained, but his place among the pantheon of Indian heroes is safe and sound. Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose's Life, Politics & Struggle is, if at times stultifying, an informative and absorbing read.

GM Shahidul Alam is Adjunct Professor, Independent University, Bangladesh (IUB).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments