Unpacking the craft of creative writing

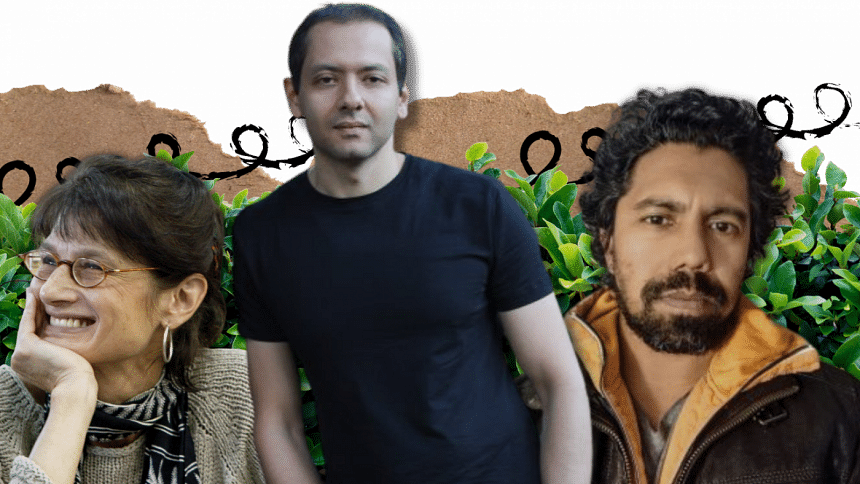

November 15-22 saw aspiring novelists gather in a creative writing residency in Sri Mangal. Organised by Bangladeshi-Canadian writer Arif Anwar, author of The Storm (2018), the residency was mentored by award-winning writers: Joan Silber, American novelist and short story writer of nine works of fiction, most recently Secrets of Happiness (2022), and Egyptian-Canadian novelist and journalist Omar El-Akkad, most recently the author of What Strange Paradise (2021). In conversation with DS Books editor Sarah Anjum Bari, the three authors discuss the craft of creative writing and publishing.

Tell us about the residency.

Arif Anwar: The idea from the start was to build a close-knit, small group of students which would yield high mentor-student ratio and to build a temporary community that dissipates creative energy. We're all eating together, spending time together. A lot of the conversations around creative writing are emerging organically.

There's been six lectures so far from the two mentors each. Within the sandbox of a topic, they could talk about whatever they wanted. Joan offered to talk about time. Omar is focusing on revision and pace. The idea was to organise it the way the work of a novel would unfold.

Joan, what is the one advice you give to students when you're discussing the use of time?

Joan Silber: That the length that a story needs determines its meaning.

I talk about short times and long times. I talk about what I call classic time in The Great Gatsby—how it uses summary to give backstory. We both used examples very strongly and gave out a few generalities. That's how writers always learned to write. Long before we had writing classes, writers observed what they loved in other books.

You've both travelled a lot. Has that impacted your writing, and how does a place like Sri Mangal affect it?

Omar: Absolutely. I grew up on one side of the world and then I came to North America when I was 16, so already I wasn't anchored in one place. One of the things about travelling for writing is that you get a very unique experience of the place. You're surrounded by other writers. It reminds me of how different the prisms are through which readers read your work.

I steal a lot from different literary lineages, from the western canon and Arab writers. The result is a weird hybrid that's hard to pin down. It used to confound me because a lot of my favourite writers were marinated in any one spot. Over time, it's become more comforting to know that I'm permanently unanchored.

Arif: Social scientists have written about the world in terms of a centre and a periphery. The centres are Tokyo, London, New York. Peripheries are Dhaka, Senegal, Lima. But peripheries have their own centres and peripheries. For Bangladesh, Dhaka is the centre and Sri Mangal is the periphery. The idea for me was to challenge these cosmopolitan centres that we associate with fine art.

Omar, how do you toggle between fiction and nonfiction?

Omar: I think of them as antagonistic muscles. Journalism by necessity is about finding answers. Fiction is where I go to sit with questions. I feel no obligation to provide a roadmap for any kind of answer.

The best thing I ever did for my fiction writing was 10 years of journalism—it was an editing and writing education—and for my journalism career was to take a bunch of creative writing classes. It allowed me to differentiate my writing from 50 other interns who were sent to report on the same car crash.

What really goes into editing a manuscript?

Omar: The first process is interior. You're rereading your own work, you're reading out loud. And then it's a concentric circle growing outwards—your trusted friends. At a certain point you hit a boundary between the personal and the commercial: you're getting prospective editors or readers to read it—people who will have a business angle to the work. That's a very different kind of reading, because now people are thinking about whether this will sell. What demographics can be interested in this? How can we market it?

How does one balance that line between taking constructive feedback and preserving the essence of the text?

Arif: Sometimes a writer knows what the text is about before they finish the writing; sometimes they need those other eyes to tell them what it could become. Whether you have that willingness and openness depends on how strong a sense you have of what you need from the beginning.

With your first novel, I think you're a bit dazzled. Having an agent or publisher for the first time, you're willing to cede a little more ground. I didn't have as strong a sense of what my first novel was. With my second novel, I'm less open to directional input.

Joan: With students you can sometimes identify—oh this is the part that sounds most like them. Usually it's the part where they don't sound like anybody else.

These days we have the diasporic novel, the refugee novel—books about sensitive topics. Who gets to tell which story?

Joan: I often get asked, has anyone objected to you writing a Thai-American or an African-American character? The whole story is never told from that point of view, it's a certain section of the novel. I've never gotten flack, probably because I'm not talking directly about race and ethnicity; I'm talking about love and sorrow, which emotionally I'm equipped to do. It's forever delicate.

Omar: I don't think it's so much about who can write what as it is about who gets published. By definition, any industry is going to cater towards the set of experiences that are more resembling that industry. The overwhelming publication of a particular kind of writer at the expense of others is where this debate is at its most useful. It is at its least useful when we're telling individual writers: write about this, don't write about that.

But when a writer is trying to work with several different types of characters and there comes a point of choosing a narrator or a point of view, how is that something that a writer can approach?

Joan: I think trial and error is our strongest device. It's just amazing how much of writing advice really falls into failure and then repeat.

Could you give us some more idea about what goes into the creative writing workshop?

Arif: We sit at a round glass table in a manner that no one is really at the head of the table, and then the mentor speaks about a particular topic. Sometimes we will raise our hands if we have any questions, and this happens for about an hour. We have separated the workshop discussions over particular submissions, so that is a separate discussion. The idea is more or less about craft and the discussion of the craft between the writers and students. In the six lectures that we have had, the primary idea is to germinate these ideas about writing and then just work on it.

There is this idea that creative writing workshops in the West are not inclusive of non-Western forms of storytelling. What are your opinions on that?

Joan: I think that there is an effort to change it.

Omar: Yes absolutely. There is a novel which came out earlier this year titled If an Egyptian Cannot Speak English by an author named Noor Naga, and the entire third section of the book is the transcript from a writing workshop where an author has brought in a manuscript that is from outside of the West.

So, for me, the two most important things about a workshop are the connections you make with the other writers in the workshop and the other part of it is to learn to give and receive critical feedback. To understand why you like this or why you dislike this are important parts of the process.

Would you like to suggest any books for creative writing?

Arif: One thing I have noticed about mentors is that there are more than one million writing instruction manuals on the shelves. So, you read like a writer and read the works of other authors and try to figure out why you like this and understanding what they are doing. It sounds very mechanistic, but it's very helpful to understand the craft techniques the writers you admire are using and what are the variations you can introduce and what is the space to explore.

Omar: The book which Stephen King wrote — On Writing — does a bunch of things at once. He gives you really pragmatic and practical advice and he is honest about what he is trying to do. There is a segment where he says that he is not gonna turn you into Faulkner. No writing instructor can take someone and make them great. You can take someone who is good and make them a little better. He is honest about the industry too, and talks about how much he sold his first book for. In the middle of all of this, he tells the story of him being hit by a car and almost dying. So it's a really fantastic book in the sense that it is doing ten different things at once which is a hard trick to pull.

Joan: There are a few books that I really like, but I don't really rely on them. So, I am trying to find a way for everybody to do it in their own way, including me.

Could you shed some light on the process of getting in touch with an agent and having your manuscript reach publishers?

Omar: It is scary. Sometimes, you just get very very lucky which is what certainly happened in my case. It really has to do with the right time and the right circumstances, and not the quality of your work, so it is not really something that you can teach. I think that there are certain things which I like to press. If you are reaching out to an agent, go and find out exactly what sort of work that agent publishes. Also, think in terms of what would differentiate your work with the work of 39 other authors. I try to work with students on mini sales pitch paragraphs to get them to think about those things.

If you are a Bangladeshi author wanting to get published abroad, what does the process look like?

Arif: It's tricky. I do think that in the publishing industry authors of colour are reduced to blocks. For example, an editor in a renowned publishing house once reached out to me and said that they really liked my book but could not publish it in the quarter as their marketing manager had reminded them that they already had a book from Bangladesh being published in that quarter.

I do think that it is a bit of a different landscape now compared to 2016 when my novel came out. Authors of colour have found massive success in different genres, such as fiction and sci-fi. I do think that the gatekeeping aperture which was so tiny is opening up a little bit. So, go out there and be confident in your writing and write a compelling story and I do think it has some chances of success.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments