A little-known initiative to help the 'war babies'

One of the most important initiatives that Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman undertook post-Liberation War was enacting the Bangladesh Abandoned Children (Special Provisions) Order in 1972. Unfortunately, not very many people are aware of this initiative that is deeply significant for our national history.

After assuming power, Bangabandhu's first priority was to rebuild the war-torn country, but while doing so, he recognised the grave problem regarding the birth and simultaneous abandonment of the children who were born as a result of mass rape by Pakistani soldiers and their associates. All throughout 1972, newspapers such as the Daily Azad, Purbosesh and Daily Ittefaq referred to the war babies as "unwanted" or "enemy babies" of Bangladesh.

Bangabandhu took quite a different position and stood up for these babies, calling them manobshontan (humanity's children), echoing the same sentiment expressed by Mother Teresa.

Contrary to his administration, the Bangalees' indignation for the newborns displayed a more insidious form of bias prevalent in Bangladeshi society. People's attitude towards the war babies was shaped by a careful choice of terms, such as "unwanted" or "throwaway", the objective of which was to intentionally denigrate the status of war babies in their country of birth.

Personally, Bangabandhu was particularly sensitive to, and seriously mindful of, the fact that negative attributes to the war babies had already made people see them as "undesirable" and, therefore, "disposable." Unsurprisingly, he wanted to do something positive so that the supposedly unwanted babies might find safe homes, where they would receive love and affection.

However, right at the outset, the government encountered a serious problem: there was no special legislation in Bangladesh governing adoption. The only applicable laws at the time were the Guardians and Wards Act 1890 and the Muslim Family Laws Ordinance for the purpose of guardianship. Under the act, "guardianship" of a minor is permitted by a competent court if it is deemed to be "in the best interest of the child."

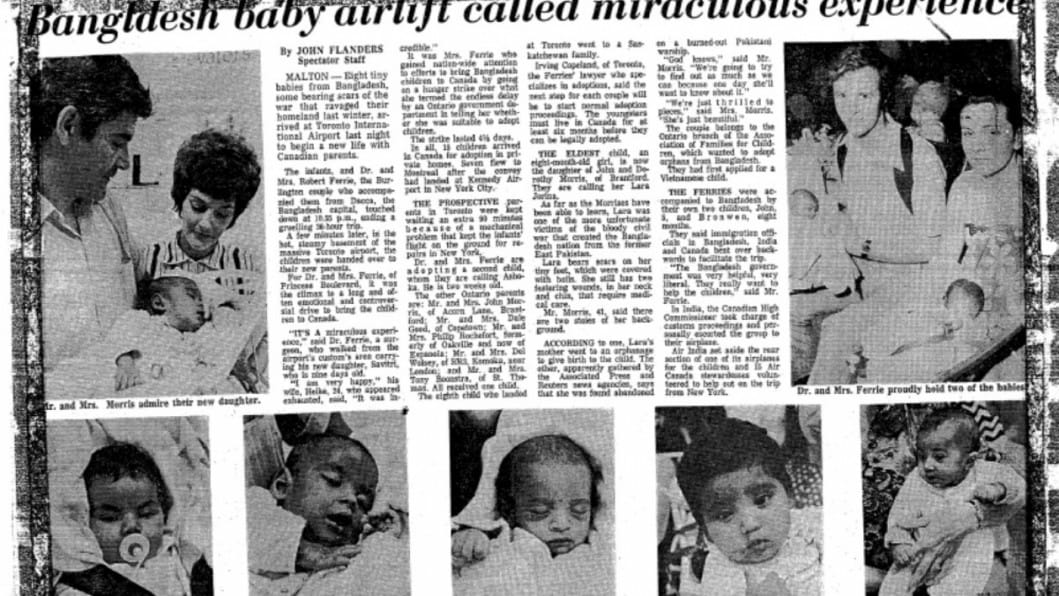

Simply put, the Muslim law does not allow adoption in the way it is understood by Western countries. Death, illness, and economic hardship of biological parents are generally the precipitators of guardianship among extended family members and foster care placements in orphanages and/or institutions. Two key factors – Bangladeshi war babies, and a group of Canadian couples' quest for children – epitomised the story of parenting beyond genetic lines. Fearing that political and religious leaders would play "hardball" politics, which could result in further stigmatisation, Bangabandhu's administration kept a low profile but diligently worked with key players such as the Geneva-based International Social Service (ISS) as well as national stakeholders, keeping in mind the best interest of the children.

Those in charge, while conducting research on the prospect of adoption of the war babies, recognised that, historically speaking, adoption had been a matter of what is usually referred to as "informal" adoption, whereby an orphan is taken into a home and raised as one's own child. Except that it is never legalised.

In sum, the very landscape of adoption in Bangladesh is different in that adoption is seen as a "paper" kinship in the absence of conception, creation, gestation, and birth.

And given the muddled and ambivalent attitude towards adoption, Bangabandhu put the matters somewhat iconoclastically to counter social ostracism and alienation, and the moral and political dimensions of adoption. Evidently, the birth mothers were abandoning their babies and did not wish to take any responsibility for those whose birth was associated with stigma at a time when the putative fathers of such babies were absent. As the "statutory guardian" of the war babies, Bangabandhu had to take steps to save their lives by finding safe homes with parents who were committed to raising these babies as their own.

Bangabandhu was quite disturbed to see the predicaments of the war babies, and urgently sought counsel from the ISS for some recommendations in this regard. He sought its counsel in the hope that, given the socio-religious feelings of Bangalees, the organisation might see the issue from a broader perspective and recommend an appropriate solution. This was a time when Bangabandhu recognised that he was under tremendous pressure but had no capacity to initiate any tenuous social, institutional, or administrative changes, even though he believed there was a need for change.

After three months of study, the ISS recommended that the war babies would never be accepted socially in Bangladesh. In fact, it was feared that these "unwanted" children would be discriminated against in Bangladesh due to the way in which they were looked upon, having been conceived via rape. The ISS recommended the war babies' adoption as an alternative.

Receiving ISS recommendations, all cabinet members of the government were on the same wavelength in terms of the desired changes to be affected in Bangladesh. They were solidly behind Bangabandhu and reviewed the complicated process of foreign adoption and its applicability. Despite his heavy workload, Bangabandhu took special interest in the matter and wished to resolve it legally through the enactment of appropriate legislation before the problem of abandonment got out of control.

Given the sensitivity of the issue at hand, the government, however, needed to clarify where it stood on the issue of trans-racial adoption outside of Bangladesh, as per the ISS recommendations. Ongoing consultation with the ISS personnel had, no doubt, helped the key officials gather sufficient information about the risks and develop mitigation strategies accordingly.

The child welfare agencies under the Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare and the Ministry of Law and Parliamentary Affairs were assigned to draft appropriate legislation that would allow the infants to be sent to Canada and other countries where the prospective applicants (or future adoptive parents) had agreed to an undertaking for adoption. It would be interesting to note that, in the minds of Bangladeshi legislators, the linguistic juxtaposition had shown the oscillation between reason and passion that ultimately helped them come up with a special provision order. In doing so, they were inspired by a new impetus initiated by Bangabandhu, who wanted to construct a particular norm and the adoption of values in his Sonar Bangla (Golden Bengal).

While crafting the special provision, government officials were acutely aware that adoption policies and practices around the world must serve the "best interest of the child," a common phrase in the formulation of children's rights. In developing the special provision order, they were thus guided by the stellar principle, working on the premise that the well-being of the war babies must be given priority.

Within months, the government of the day came up with a legislation that not only clarified but also strengthened the legal protection of children, removing deterrents to effective action for such children in Bangladesh. It is called the Bangladesh Abandoned Children (Special Provision) Order, 1972, the legislative response to the ISS recommendations. In clarifying the clauses within the special provision order, the government was careful as it did not in any way want to get mired in confusion and controversy. Personally, Bangabandhu believed that his government acceded to adoption outside of Bangladesh, having made a thoughtful and informed final decision based on an ethical framework regarding interracial adoption. In doing so, Bangabandhu also believed that adoption should be an unfaltering commitment to providing families for children, rather than children for families.

As the government continued its work, it realised that adoption still remained a controversial topic at that time and the associated controversy within social work and allied professions reflected a general lack of consensus with respect to certain fundamental childcare principles. Given the prevailing sentiments against the notion of being "unwanted," it recognised that placing a war baby with a Bangalee family did not necessarily ensure a perfect match. As far as the government was concerned, even though there was a lack of social reform, the proposed special provisions order had to be drafted to ensure legal transfer of guardianship beyond Bangladesh.

This single document became even more significant when one recognised the fact that it was drafted under unusual and pressing circumstances where previously there had been no legislation governing adoption in Bangladesh. The government made sure that birth mothers' informal or secret abandonment of their babies was done legally.

Simply put, the primary objective of the presidential order was to establish "legal guardianship" of abandoned infants, and to provide certification of birth for children legally free for adoption both in and outside of Bangladesh. The "statutory guardian" in the absence of natural parents was mandated to authenticate the prospective adoptive parents from abroad who had already obtained clearance from the governments of their respective countries. In doing so, the government was extra careful, having recognised that adoption connotes a redefinition of parenthood, legal and/or formal establishment of a parental relationship that is not biological or genetic.

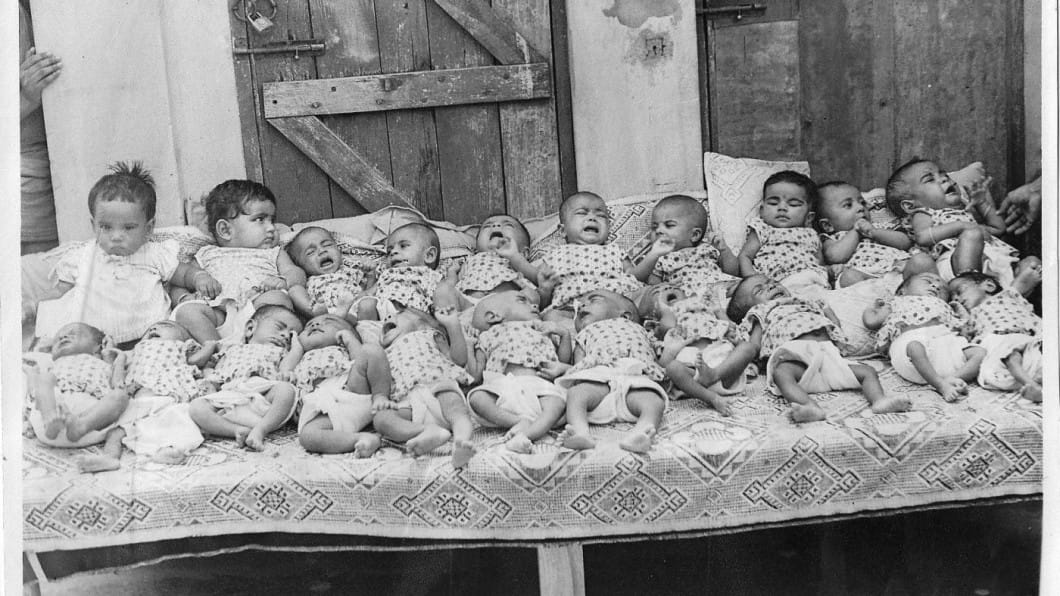

The government designated Sister Margaret Mary, the then superior of the Missionaries of Charity located in Dhaka's Islampur area, as the "statutory guardian" of the abandoned war babies in the following manner: "The statutory guardian may deliver an abandoned child for the purpose of adoption to any adoption agency in or outside Bangladesh on such terms and conditions as may be prescribed and as such delivery shall constitute a valid adoption." The proclamation also defined an abandoned child as a child who, in the opinion of the government, is deserted or unclaimed or born out of wedlock. These children were, therefore, considered to have become the "wards" of the state and, as a result, the government ensured that the war babies were not thought of as chattels to be passed by deed from one family to another, or one country to another.

Upon assuming "statutory guardianship," Sister Mary's prime responsibility was to endeavour to lessen the stigmatisation of these infants by making them available for adoption to couples who would assume their parenthood. The ordinance, as a whole, dealt with social attitudes, seeking opportunities to educate and liberalise public thinking, having symbolised life and hope of better health and bearable conditions for the war babies.

It is important to note that although originally it was intended for only war babies, the law in its final form was applied to all "abandoned" children, thus providing a new lens through which to view the predicament of the orphans and then propose solutions.

Given the complexity of the issue, Bangabandhu knew that his government could not come up with a perfect solution. Since the cabinet members were on the same wavelength in terms of the desired changes, they were advised by Bangabandhu to take the time they needed – especially those in charge of writing the law to reflect on the issue and craft the legislation with forethought. This is why Bangabandhu's name will remain etched in history forever for his contribution in enacting this ordinance to legalise adoption of war babies.

Nevertheless, there were a few who came up with muted but shrill criticism. Having certain serious misgivings regarding adoption, they saw the government's initiative to create a family as being in the "best interest" of "unwelcome" children who were being born and abandoned at the time.

By and large, however, the people of Bangladesh were glad to learn that Bangabandhu was successful in resolving the problem of the "unwanted" war babies. We must conduct more research on this initiative of Bangabandhu, about which nothing has been written thus far.

Mustafa Chowdhury is an independent writer and researcher, and author of "Ekattorer Juddhoshishu: Obidito Itihash" and "Unconditional Love."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments