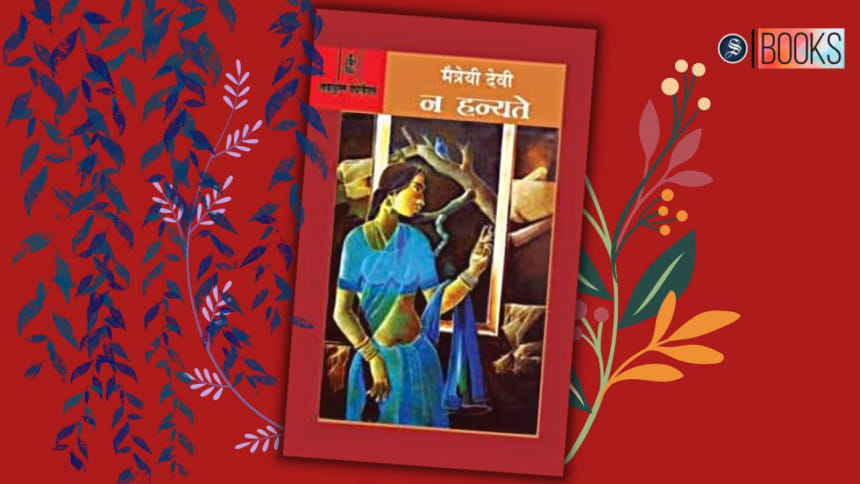

Love does not die in Maitreyi Devi’s 'Na Hanyate'

William Faulkner once said that the only thing worth writing about is the human heart in conflict with itself but Maitreyi Devi, a protégée of Rabindranath Tagore, in her Na Hanyate (Radhakrishna Prakashan, 2010)—first published in 1974—deftly depicted more than just a human heart in conflict with itself. She portrayed a story of two hearts deeply in love but unable to converge for societal reasons. With stark clarity, Indian poet and novelist Maitreyi Devi shows us the preposterousness and irrationality that was so pervasive in the social milieu of 1930s Kolkata.

Sahitya Akademi Award-winning novel Na Hanyate does not quite fit into any particular genre, though it is often regarded as a semi-autobiography; it reads more like a fiction, a novel crafted in a writer's head, than something real which took place. It was written as a reply to Mircea Eliade's La Nuit Bengali (Gallimard Education, 1979)—an exaggerated and sensationalised tale of his love with Maitreyi Devi, which according to her holds little truth and more fiction.

La Nuit Bengali was published in 1933 in Romanian and Maitreyi Devi got to read it four decades later. The version of their love Mircea depicted infuriated Maitreyi as she was portrayed as a caricature of a mythical goddess, transforming her inexplicably from a 16-year-old to an amorous queen in his own unrealistic, self-indulgent fantasy. So Maitreyi Devi took it upon herself to tell her side of the story, of what actually transpired four decades prior to that.

Na Hanyate begins in 1972 with a 56 year-old Maitreyi Devi, who starts to reminisce about her teenage days—days spent with a certain Romanian man named Mircea Eliade who came to India to study under the tutelage of her philosopher father back in 1930. As time went by, Maitreyi and Mircea's continuing interactions led them to fall for each other and the romantic relationship that unfolded between them eventually could not come to fruition because of cultural constraints.

That Maitreyi Devi could love someone of not her own creed and even think of marrying him was tantamount to heresy even to her rather progressive, scholar and philosopher father, Surendranath Dasgupta, who—for all his pompous talks of morality, ethics, opposition of superstitious culture and teachings of liberal education and values to her daughter—could not and perhaps willfully did not let her daughter marry the person she loved. Whilst not being successful in marrying or being with the person she loved for her family's restraint, we still see a defiant Maitreyi Devi adamant to not respect the customs of a prejudiced society that held more sacred, more valuable, anything else above humans and love—even if that defiance was only in her mind which for her was at least a place where her father had no control over.

While talking about rebels wanting to liberate the country from the British, the author cannot help but ask the question of who will liberate the people—people like her and her mother who, even after being in the most progressive of the families, could not do what their hearts desired and were perpetually subdued. After all, what good is independence and an independent country if half of its population are repressed by the other half in ways and through institutions that cannot be overthrown as simply as dethroning a foreign power?

In Na Hanyate, hearts are hurt and scarred in the saddest of ways. When the author in her late 50s, reminisces the days she spent with Mircea four decades ago, the days which she thinks are the only days in her whole life when she actually lived and not just existed, it reminds one of Seneca's telling, and the life of Maitreyi Devi rings as if she truly lived only for the short time she spent with the love of her life, Mircea Eliade.

Maitreyi Devi in her book prudently paints a kaleidoscope of emotions; of love and heartache, of pleasure and agony, of nostalgia, and dejection, of craving and abjuring, of submission and defiance, and of trust and tryst.

Najmus Sakib is a contributor.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments