Afterthoughts on Dhaka Lit Fest

What the capital witnessed during this year's Dhaka Lit Fest (DLF) was nothing short of brilliance. The stellar presence of Nobel laureates, Booker International, Booker Prize, Oscar, and Masterchef winners, among others, made the 10th edition of the DLF truly exceptional. Neither the coronavirus-inflicted hiatus of three years nor the exceptionally fog-canopied cold weather could dampen the spirit of the fest. Dhaka won the hearts of the visitors, as is evident in their many complimentary remarks. And there was much to learn from visitors themselves.

In its 150-plus sessions, participated in by 500 speakers and panellists, the four-day event celebrated the theme of coming together through stories. We heard stories of different kinds – of sports and music, of genres and genders, of struggles and survivals, of place and memory, of humans and non-humans. Above all, we heard stories of the triumphs of science – innovations that helped us navigate through the pandemic. We also heard about the importance of stories – both big and small. We heard how travelling to Dhaka changed the minds of our honoured visitors; how the event put us on a global map.

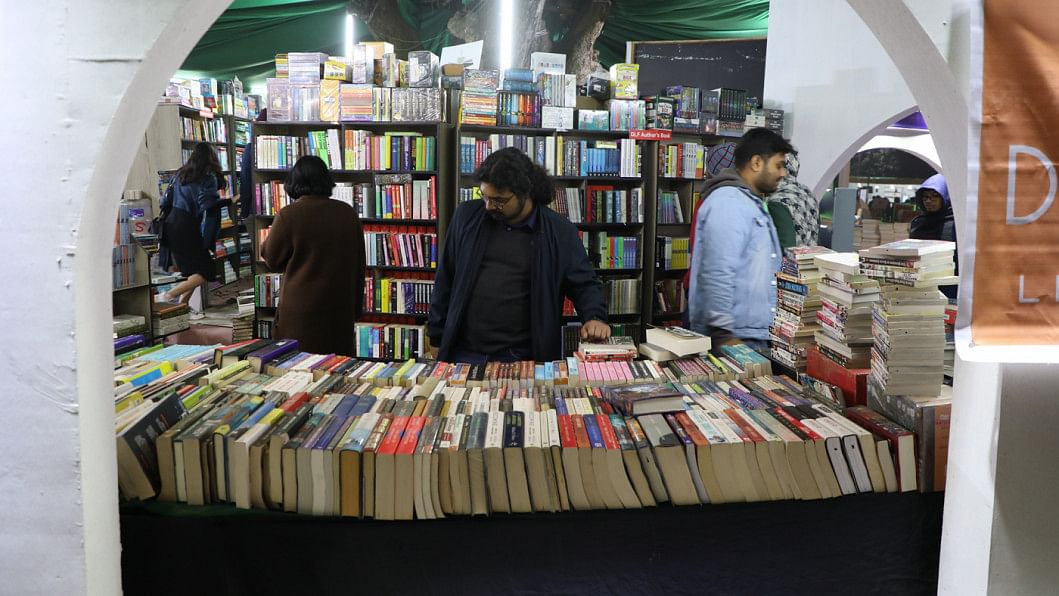

Meeting the writers and thinkers in person, who have the special ability to present the world in words, asking them questions on specific issues, sharing a selfie moment or getting a copy of their book signed are all part of the DLF package. The ambience was great, with a lot of screenings, interactive sessions, activity corners for children, mind-blowing performances, and a wide range of book and food stalls. The only glitch in the system was the introduction of tickets for the first time. The price was deemed too much and social media became divided in its characterisation of DLF as an "elite fest."

In their pre-event press conference, one of the three directors of DLF, Kazi Anis Ahmed, mentioned that the subscription was needed to reduce the dependency on corporate sponsorship. But critics seemed unconvinced and unsatisfied. They sensed a deep-seated conspiracy to turn culture and literature into a profiteering scheme.

The commodification of art is a notorious topic. While the sensory perception of artwork, painting, or sculpture initiates a cognitive and emotional process, paying for such an experience is another ballgame. Art has traditionally benefited from a culture of patronage. People in positions of power have historically funded artists to outfit their homes or homelands and writers to narrate their lives and experiences. The Medici family, for instance, was responsible for the majority of Florentine art during the Italian renaissance. The same can be said about the Nauratnas (nine gems) in the courts of the Hindu emperor Vikramaditya, the Mughal emperor Akbar, and the feudal lord Raja Krishnachandra.

However, some artists are not willing to put a price tag on their creativity.

The nature of the sponsors has changed over the years. From the religious commissioning of churches to charitable foundations, and from the sponsorship of aristocrats to that of plutocrats, there has been a radical shift in the artistic and literary world. With the hefty inflation of art prices and the celebrity status assumed by writers, the shift involves an obscene amount of money.

DLF is an expensive affair. I am not in a position to comment on how much of a ticketing fee is right to make an event of the stature of DLF viable. I am rather interested in a tangential strain of thought I picked up during this meeting of minds.

Two young members of the audience, at a session on climate change on the first day of DLF, objected to the playful tone of the panellists. One compared the scenario to that of the musicians who played their instruments to calm the passengers of the Titanic in the ship's final moments of sinking. Is the aesthetic response of artists, to offer therapeutic or cathartic readerly experience, enough to address the "doomed" Earth? The second comment was more direct, as a young woman felt that we should simply pursue climate activism like Greta Thunberg does.

These questions challenge the validity of art at a time when the planet we share with other species is dying due to the irresponsibility and indifference of humans. While artists have been expanding the scope of social conversation by shaping the imagination of their readers and viewers about the nonhuman world, climate activists have long felt that it is not enough to keep on beating the old drum of ethical responsibility in an imaginative space.

Last October, climate activists across the globe started a unique protest by glueing themselves to several iconic art pieces in European museums to raise awareness about climate change. Two groups of young activists, under the banners of Ultima Generazione and Just Stop Oil, vandalised many paintings to point out, "Maybe they don't understand that the inconvenience we created is nothing compared to one billion climate migrants and the many deaths that the climate crisis is causing already."

Is it possible for art to be an ally in promoting the climate conversation?

Amitav Ghosh, who attended DLF as one of the featured authors, recalled how his ancestral homes kept changing with the changing course of the River Padma. The vulnerability he faced as a climate migrant had a lasting impact on his creative and intellectual makeup. His novels have been instrumental in expanding the social conversation about climate change by inviting his readers to imaginatively engage with the world that we inhabit. His work inspires us to retool our inner climate while acknowledging the fear and guilt that dominates the climate conversation.

The two young individuals who asked the questions during the aforementioned DLF session seemed less convinced that art and artists are doing enough to save the world.

In another session featuring Amitav Ghosh and Abdulrazak Gurnah, a 15-year-old schoolboy stood up to ask what advice the panel has for their 15-year-old selves. The panellists ducked the query.

For me, these questions by our young generation have been the highlights of DLF 2023. The fest provided a space where the current generation can rise to the occasion and raise questions. Such space is more and more getting squeezed in Dhaka. DLF, with its international orientation, opened it up.

We must curate many such moments and occasions. I am sure by now DLF has created many friends who can take up a financial plan to make the greatest show in Dhaka easily accessible. It is important that our young generation gets exposed to the best minds and can then prepare to be the best versions of themselves.

Dr Shamsad Mortuza is a professor of English at Dhaka University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments