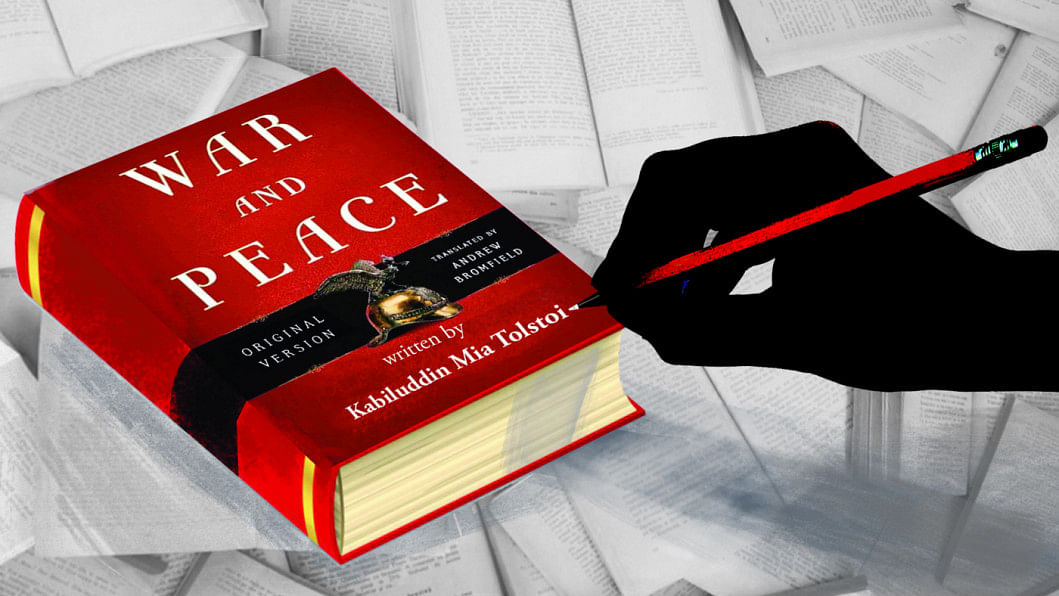

To catch a plagiarist

It goes without saying that editors of texts have a thankless job. They laboriously go over content – no matter how badly written it is –, correct spellings, reconstruct sentences, sometimes even completely rewrite the script, and make it palatable, only for the writer to receive all the applause. It's a behind-the-scenes job that remains invisible. And yet, without it, everything would fall apart. Which is why when we editors get an engaging, well-written, well-argued, and error-free piece, we get a kind of high from the sheer joy of reading something for the pleasure of reading, without the constant hiccups of all the decoding and deconstructing.

Then, we feel dread. If the language is too flawless and the writer unknown, if the nit-picking editor cannot put a single mark on the script, chances are that it is too good to be true.

In the newspaper industry especially, among the tsunami of outside contributions, only a handful turn out to be in the category of the brilliant and excellent, and even those will have at least one or two minor errors – dashes and dots mainly, or a silly typo. Otherwise, it is most likely someone being too clever and passing off someone else's work as their own.

The recent hullabaloo on social media about a section of a Class 7 science textbook being allegedly plagiarised from the National Geographic website shows how insidious this practice is and how often it can go undetected. In this particular case, the section was Google-translated to Bangla, which is what really clever plagiarists do and often get away with. Professors Zafar Iqbal and Haseena Khan, the editors of the book, have admitted that they checked and, indeed, the text had been plagiarised, conveying that they were very embarrassed that it had gone unnoticed.

While people are ranting against the editors, they really should stop to think how difficult it is to suspect a Bangla text to be plagiarised if the original content is in another language. The person who first made the discovery must have really gone deep in his investigation, because he would have had to re-translate the Bangla piece to find out that it was a translation of an English script, because Google translate is not always very reliable and can come up with the most bizarre results. So kudos to the person who exposed the theft and also to the editors for quickly acknowledging that it had occurred – although they were not involved in writing that particular section – and assured that this was not the final version of the book.

But what about the particular writer who took the section and glibly passed it off as his own work? The obvious thing to do would have been to admit their own laziness and give credit to NatGeo. The most ethical thing to do would be to write to NatGeo and get their permission, which may or may not have been procured. By not acknowledging the source, however, the writer broke the trust placed on them by the editors and made them take the flak for their own dishonesty. The worst part is that it is unlikely that the person in question will get any more punishment than an exclusion from future textbook writing, which is hardly a deterrent for the next plagiarist.

What is mind-boggling is that certain writers feel no compunction about just lifting whole paragraphs from others' texts and inserting them in their own pieces. The most common culprits are students who need to hand in many essays and papers in their academic life. Despite all the warnings of dire consequences if they are caught, some students will take the risk of stealing content from other papers, sometimes even buying entire papers written by someone else and handing those in as their own work. The incidents of university professors submitting papers with plagiarised sections is perhaps the most shocking. When teachers – who are responsible for imparting knowledge to others – resort to such deception, what message will their students get?

Ironically, Google, which has provided a limitless supply of such perfect writing to steal from, can track most such intellectual robbery with just a simple search of a sentence from the text. These days, there are special plagiarism trackers that can track sentences and paragraphs that have not been cited or attributed properly. Imagine how much material had been stolen all those years before Google!

Apparently there is also a thing called unintentional plagiarism when someone "forgets" to cite content taken from somewhere else or when one presents an idea thinking it to be their own when in fact it was, say, Milan Kundera's. These unintentional plagiarists mean no harm and are either somnambulant when they steal or just scatterbrained, though they are still committing a crime. There are also "plagiarists-in-denial" who, no matter how many times you send them the piece with highlighted sentences that they have clearly "taken" from other texts and inserted into their own articles, will still insist that it was just coincidence!

Shabby plagiarists are those who forget to change the font of the parts they stole, or forget that their own language skills are quite poor and the beautiful sentences they have lifted stand out like precious stones in a pile of garbage. Meanwhile, "accidental plagiarists" diligently attribute the paragraph or idea to the source they had found online, but it so happens that the very source is fake and the attributed paragraph has actually been lifted from somewhere else. Talk about rotten luck!

But most plagiarists are well aware that they are stealing stuff from someone else's hard work and feel no remorse about it. Thus, for editors, no matter how gruelling their hours and how brain-numbing their work, checking for plagiarism is really worth the trouble. It will not always be foolproof but in many cases will expose this intellectual poaching and help one avoid a lawsuit or zealous public shaming on social media.

Aasha Mehreen Amin is joint editor at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments