Ordinary citizens’ vulnerability to custodial torture

Within a fortnight of celebrating Police Week, two incidents have brought to fore the question of extrajudicial excesses of the force. In one incident, a youth protestor was subjected to police brutality in custody in Chattogram, while in the other, a trader allegedly died due to custodial torture in Gazipur.

From a tender age, Mohammad Mostakim has faced the hard realities of life. After his father passed away years ago, the 22-year-old madrasa student has been the anchor of the family. Mostakim has to look after his 55-year-old mother (a kidney disease patient requiring dialysis three times a week) and a 10-year-old physically challenged sister. He meets challenges with fortitude and as a conscientious citizen who is actively engaged in local efforts to combat the Covid-19 virus.

It is no surprise that Mostakim became part of the group of kidney patients and their relatives protesting the price hike of dialysis treatment and reduction in subsidies. On the fifth day of the protest, when protestors blocked the road in front of the Chattogram Medical College and Hospital, the police used force to disperse them. Subsequently, police filed a case in which alleged victims of police assault were charged with "obstruction of government work and attacking police." Mostakim was arrested along with 50 to 60 others. Five days after his arrest, Mostakim was granted bail and the police's application for a five-day remand was denied by the magistrate.

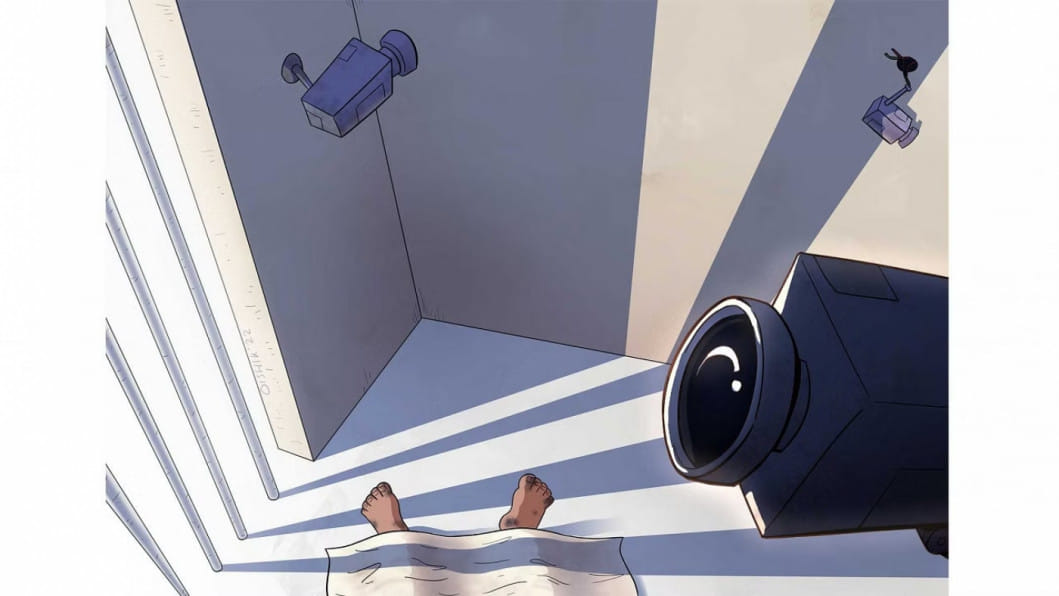

The police's heavy-handed approach in dispersing a crowd that was peacefully protesting the price hike of a medical service, and its subsequent slapping of cases against a number of the protesters, has appalled citizens. The situation dipped to a new low as Mostakim was beaten in custody purportedly to get a lesson for "disrespecting" the officer-in-charge of the local police station. Photographs of his bruised left leg aptly conveyed the brutality Mostakim had to endure.

The treatment of Mostakim and his fellow protesters by the police raises the question of whether the state has effectively abrogated the constitutionally guaranteed citizens' right to protest. The administration also needs to make clear in what ways this group of aggrieved citizens violated the laws of the land, triggering such violent and disproportionate response from the police. Even if the group was impeding the flow of traffic, were there no non-violent and civilised ways of tackling them?

The vicious bodily harm inflicted on Mostakim in custody betrays the intensity of contempt that some members of the force hold against citizens who still dare to exercise their rights to express and assemble.

The second case of Rabiul Islam of Gazipur shed light not only on alleged custodial torture leading to the death of the victim, it also revealed how members of law enforcement agencies allegedly fabricated stories to cover up their misdeeds.

On the evening of January 17, Nupur was informed by the police that her husband Rabiul had died in a road accident following his release from custody. Family sources inform that days earlier, along with three others, Rabiul was picked up by two assistant sub-inspectors of the local police station on charges of gambling. The 45-year-old victim was detained in the police station while the three co-accused were released. When police personnel demanded money for releasing Rabiul, on January 17, Nupur handed over Tk 35,000. After securing the amount, instead of discharging Rabiul from their custody, police demanded an additional sum of Tk 5 lakh. Subsequently, they promised to release the detainee when Nupur complied with their instruction to put her signature on a blank sheet. On the same evening, she was informed by the police that Rabiul had been hit in a road accident and shifted to Dhaka Medical College Hospital (DMCH). When the family arrived at DMCH, they found the body of deceased Rabiul. Refuting the police narrative, his family and people of the locality have asserted that Rabiul was tortured to death.

Rabiul's death, allegedly a result of police torture, triggered spontaneous protest in the area leading to road blockade, vandalising of police boxes, and torching of three police motorcycles. The police's claim that Rabiul's brother Mohidul had filed a case against the truck driver that allegedly hit Rabiul also turned out to be sham. Mohidul denied lodging the case, providing evidence that he was at DMCH to claim his brother's body at the time of the complaint being lodged. There was also a mismatch regarding the signature in the FIR that was filed with the police.

The handling of Rabiul's case by the police raises several points of concern. So far, the police could not provide any evidence to back its claim that Rabiul was indeed involved in gambling. Demanding and accepting money for releasing a detainee proves that extortion was the sole purpose of bringing the accused under custody. Securing the signature of a next of kin on a blank sheet also points to the covering up of the offence being planned. The family deserves an explanation as to why Rabiul was not handed over to them.

The cooked up police narrative of Rabiul's death also falls flat as the force failed to provide evidence of any such road accident in the area on the evening of January 17. Also, the police's inability to furnish any evidence, including CCTV footage, of Rabiul's release from custody further strengthens the argument that there was institutional complicity to cover up the custodial torture that led to the detainee's death.

Mostakim and Rabiul's experiences are not isolated cases. The media and rights organisations frequently report on cases of custodial torture, some of which lead to death of detainees. In many instances, the families of the deceased contested the police claim that the detainees had committed suicide in custody. Three cases from last year illustrate the pervasiveness of custodial torture.

On March 1 of 2022, Laboni Akhtar (23) had a miscarriage after she was brutalised by sub-inspector Ruma Akhter in Kashimpur police station. On July 17, Abdul Salam of Sreepur, Magura was allegedly beaten up and kicked in the chest, which the family believes resulted in his death at Magura Sadar Hospital. On August 21, a video went viral that showed two 13-year-old boys tied to an iron pole in Kulshi, Lalkhanbazar by a three-member police patrol and being subjected to torture.

Custodial torture continues to afflict the country's law enforcement system despite the framing of the Torture and Custodial Death (Prevention) Act 2013, the ratification of the UN Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment and Punishment, and firm directives from the higher judiciary. At a time when policymakers are deeply concerned about the image of the country, they must acknowledge that every person has the right to be treated with dignity and only in accordance with the law. They ought to ensure that egregious violation of human rights, such as custodial torture, no longer takes place. There is also the need for impartial investigation into all allegations of custodial torture to hold the perpetrators to account. There is an urgent need for an unambiguous political commitment at the highest level of the government to not tolerate torture and ill treatment under any circumstances or against any person. In the past, demands have been made by vested quarters to amend the TCD (Prevention) Act and weaken its efficacy.

The government must remain resolute and commit that it has no intention of limiting the applicability of the said Act and ensure that the Act is applicable to all forces. It must also commit that all officials engaged in acts of torture and ill treatment will be prosecuted and punished with penalties commensurate to the crime of torture – including those with superior or command responsibility – and that measures will be taken to ensure that confessions obtained from criminal suspects through torture or ill treatment are not accepted as evidence of guilt. There is also the need for the collection of systematic statistical data on the implementation of the TCD (Prevention) Act on the number of complaints, investigations, prosecutions, and trials and convictions.

Dr CR Abrar is an academic and human rights expert.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments