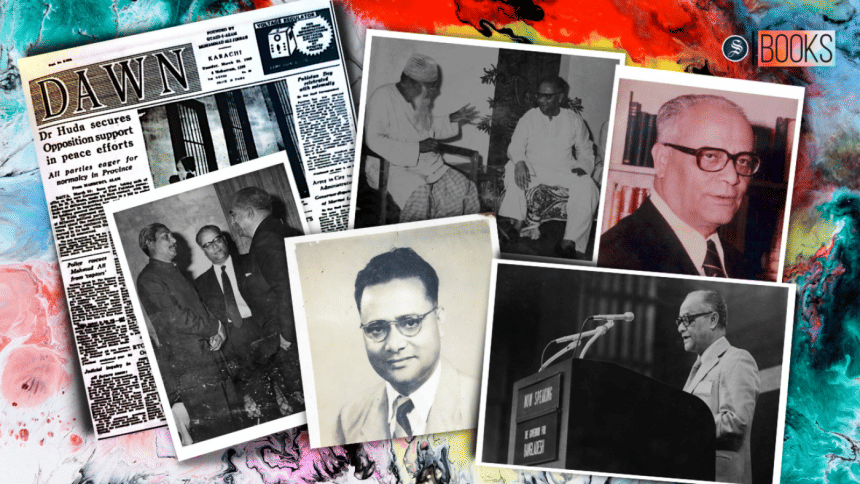

One life, and a history of two economies: Mirza Nurul Huda

Mirza Nurul Huda's memoir is a story of his life and times. Having lived through some of the most tumultuous periods in South Asian history, his memoir provides insights on many significant social, economic and political events that took place in the period. He was a highly reputed economist and professor of Economics at Dhaka University for over two decades. However, his memoir also goes into politics, society and the history of eastern Bengal, as it evolved from British India through Pakistan to independent Bangladesh.

Huda writes about his humble beginnings with rare candour, sharing many events and anecdotes about his life, sometimes related with humour, which make for lively reading.

His is an inspiring tale of a little boy with big dreams rising from the backwaters of Bengal to become a fabled student who went on to be a professor of Dhaka University, and to hold some of the highest offices in public service. The book—and its most animated chapters on East Bengal/East Pakistan—is certain to interest not only economists but also those interested in politics, history and more generally, in Bangladesh studies.

Huda was born in 1918, in a village near Tangail. His father was a school teacher and imam of the village mosque, and his mother a homemaker, who ran a maktab for girls in their home. He started formal learning in a ramshackle village school where children wrote with twigs dipped in homemade ink on banana leaves. Seventeen years later, a young Huda was to take DU by storm. He stood first class first in both the BA (Hons) in 1940 and MA exams of the Economics Department in 1941, and was the first student of the department, as well as the first Muslim student in the colonial era, to be awarded the prestigious Kalinarayan Scholarship. He later won a scholarship to study Rural Economics at Cornell University and obtained a PhD degree in 1949, in a record 18 months. At the time he was an officer on leave from the Bengal Civil Service, and on return was obliged to resume his service before being allowed to leave it. He finally joined DU as a Reader in the Economics Department in September 1949.

Noting that merit alone was not enough for Muslim students, he suggests they needed agency, which in those days came from social networks comprising murubbis and persons with influence who cared for the advancement of their community. By then, Huda was married to Umme Kulsum Siddiqua, who also obtained a Master's degree from Columbia University and joined him as a colleague at the Economics Department at DU.

In his memoir, Huda states that ideas about treating Pakistan as consisting of two units for economic planning purposes were floating in the press, but there was no clear definition of the concept until a group of eminent East Pakistani economists issued a report in August 1956. There, for the first time, they called for the necessity of "Two Economies" in Pakistan, at a special conference of the Pakistan Economic Association on the draft First Five-Year Plan at Fazlul Huq Hall, Dhaka University.

Essentially, the differences in resource endowments, levels of development, and geographic separation with little mobility of labour made it unrealistic to view the two provinces as a single producing and consuming area for planning purposes. The "Two Economies theory", he argues, originated from this thinking. The idea provoked increasingly acrimonious debates between economists of the two provinces, both outside and inside the government. The state authorities remained stubbornly hostile to it and its proponents until Pakistan disintegrated. Huda, too, experienced president Ayub Khan's rage in a meeting in 1961, where he derided them as anti-state elements involved in subversive activities to divide the country.

In the last days of his rule, president Ayub Khan appointed Huda as Governor of East Pakistan. In the backdrop of raging student protests, the challenges of the post were obvious, but after much thought, he accepted the challenge hoping to resolve the crisis and pave the way for a return to democratic rule, thereby saving the country from the hex of another military rule. Merely three days later, on March 25, 1969, Yahya seized power in a coup and imposed Martial Law. Clearly, Islamabad had different plans.

Surprised by the sudden turn of events, Huda writes: "The declaration of Martial Law on the evening of March 25 was therefore both a shock and massive disappointment for the people of East Pakistan. They saw in it yet another instance of the West Pakistani hegemony denying the East Pakistanis their legitimate economic and political rights, and shutting them out of affairs of the nation by the cabal that ran Pakistan at the highest level. If elections were allowed to be held in November 1969 as promised, perhaps the history of the country would have followed a different course. Unfortunately, such foresight, wisdom and goodwill were lacking from the civilian and military leadership of West Pakistan."

Huda chides the anti-democratic machinations of Bhutto and Yahya to deprive the Awami League from forming the government despite their clear electoral mandate, and holds Yahya's inept and indecisive leadership along with Bhutto's blatant arrogance responsible for the carnage in Dhaka on March 25-26. Huda's DU residence near Jagannath Hall was raided and looted, and he nearly lost his life at the hands of the marauding Pakistani soldiers. He provides a chilling account of his family's harrowing experience in those two days. Armed soldiers raided and looted his house twice. They pointed their guns to shoot him, but brave resistance of his wife and elder daughter saved their lives. Huda, whose faith ran deep, viewed it as a blessing from the Almighty.

He continued to contribute to development planning and policy in Bangladesh, serving as a member of President Sayem's Advisory Council, as Planning Advisor in charge of the Ministry of Planning, Finance Minister in President Ziaur Rahman's cabinet, and as Vice President under Justice Sattar as President. He resigned twice in this period, first as Finance Minister in 1980 on health grounds, and a second time as Vice President; but in both instances, the two presidents reappointed him as Advisor. After six years of public service in high offices, Huda returned to private life when HM Ershad, the army chief, overthrew the government in a military coup in March 1982 and imposed martial law.

Dr. Sultan Hafeez Rahman is Professorial Fellow, BRAC University and Director, Graduate Program, BIDS.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments