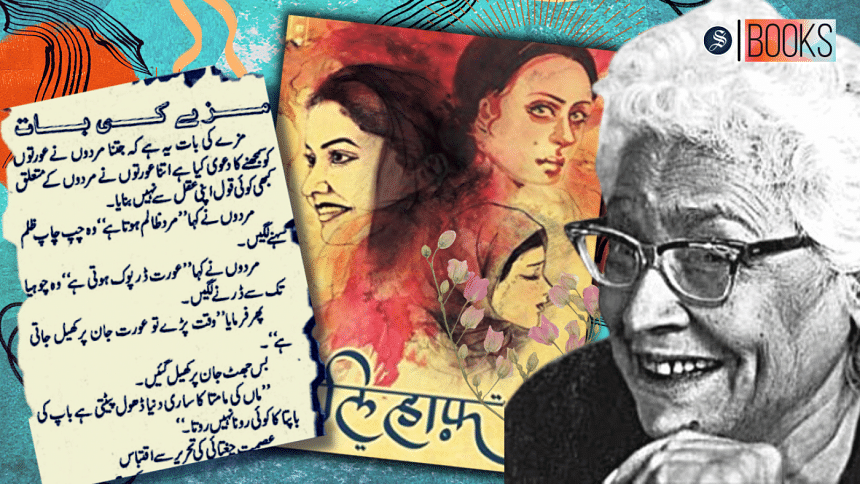

Ismat Chughtai and her stories of the unsayable

A trailblazer in Urdu literature, Ismat Chughtai was known for her bold and unflinching depictions of women's experiences through her stories.

Born in 1915 in Uttar Pradesh, India, Chughtai's writing was a reflection of the Indian society of her time, characterized by patriarchal values and oppressive norms for women. In her fearless writing, Chughtai spoke about the issues that women during her time and even today are afraid to discuss—taboo topics such as homosexuality, abortion, female desire, and their rights and independence. Her works often drew on her own life, and sought to challenge traditional gender roles.

In her short story "Gainda", the eponymous character, named after the marigold flower, is a teenage widower from a lower caste who is not allowed to express her sexual desires as a woman who has just lost her husband. Gainda is seduced and exploited by the narrator's brother but is never given the rights of a wife. The narrator's 'Bhaiya', though he loves Gainda immensely in private, refuses to publicly give her the respect she deserves, as he fears for his own public image in society. By using vivid imagery and metaphor, Chughtai exposes the unequal power dynamics at play in Bhaiya and Gainda's relationship. The metaphor of the marigold flower serves as a poignant symbol of the way Gainda is treated—as a flower used to adorn the deity during worship but discarded afterwards.

Though "Lihaaf" is considered Chughtai's seminal work, most discussed and vastly critiqued, "Ghoonghat" remains my personal favorite.

Both stories share similarities in themes and narrative styles, but differ in the portrayal of the protagonists' struggles and social contexts. In "Lihaaf", the sexual relationship between Begum Jaan and Rabbo subverts the gender role and portrays female desire as a powerful force. Begum Jaan's bold character shows her rebellion against her homosexual husband's negligence towards her physical desires. In contrast, Gori Bi, the protagonist of "Ghoonghat", is a beautiful and fair skinned woman who spends her entire life as a virgin, paying the price of her husband's fragile male ego. On their wedding night, Kale Mian's ego prevents him from lifting Gori Bi's veil; Gori Bi, for her part, is constrained by the social norms that require her to be shy in front of her husband. She too does not lift her veil, and this decision shapes the course of their marriage and their entire life.

In "Chui Mui", meanwhile, an under-aged bride (addressed as Bhabijan) faces the consequences of denying herself the agency and control of her own body, torn between what she wants and what is expected of her. Bhabijan's only conjugal duty is to birth a child and her failure in doing so legitimizes her husband's ticket to a second marriage. Fearful of forgoing her bridal comforts, Bhabijan tries to conceive as the family wants her to, but she miscarries every time. These efforts produce "a doll-like bride turning into a permanently sick woman", Chughtai writes. Women like Bhabijan still exist in our society, stripped of their bodily rights, cogitating on the intricacies of gender and sexuality.

These issues remain stigmatized in many societies including the west. Ismat Chughtai's nuanced, complex portrayal of women continues to inspire and empower women of this day to challenge patriarchal norms and assert their agency.

Atia Sultana is a contributor.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments