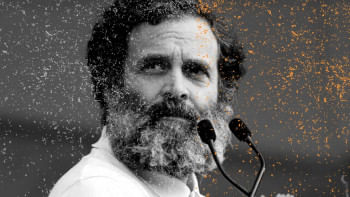

Rahul Gandhi’s conviction: Another dent in India’s declining democracy

A week after Rahul Gandhi – the most vocal opposition leader in India – was convicted in a defamation case and swiftly disqualified from parliament, political tensions in the country have soared to a new high. On Monday, the opposition parties staged a "black protest," and protesters including Congress leader Harish Rawat were detained by Delhi police. On Tuesday, more petty politics was displayed, when Gandhi was asked to leave his residence in a month.

Congress has accused PM Narendra Modi of trampling democracy, while BJP denies political intent and maintains that the disqualification – which happened less than 24 hours after the verdict – was per the law. The event has been termed as "unprecedented." Is it, though?

From Bangladesh's vantage point, the ruling BJP's move of opportunistically using the legal system to weaken the opposition ahead of elections does not seem too original. The same system that drags criminal cases for years starts to work on speed when power wants it to.

And the BJP has been somewhat predictable in terms of their antipathy towards political dissent. Take the crackdown on the BBC for example, which confirmed India's threatened state of press freedom. For almost a decade, Modi's India has been setting new precedence for introducing limits to democracy – in a way that has been far more blatant, than the 54-year-old dynasty led by Gandhi's family.

But the implication of Gandhi's defamation case and disqualification – especially the pace at which it all occurred – surely exhibits another big step in India's authoritarian lurch. It raises questions about the independence of the legal system from the Central government, and makes one wonder if India has become a nation where "anything is possible."

Congress' response that the case is political isn't unpersuasive at all. The timeline and unfurling of the circumstances is unmistakably strange. Four years ago, Gandhi stood on a podium in Kolar, Karnataka where he named fugitive diamond tycoon Nirav Modi, banned IPL boss Lalit Modi, and Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and asked why all "thieves have the same last name of Modi."

A BJP legislator in Gujarat, Purnesh with the last name Modi, found the remarks offensive and filed a complaint against Gandhi for smearing "the Modi community," associated with the lower rungs of the Indian caste community. (To note, though, this doesn't apply to Nirav and Lalit Modi, who also didn't come from underprivileged backgrounds.)

Rather fascinatingly, the BJP legislator was not offended five years ago when Khushbu Sundar, the national spokesperson for Congress at the time, tweeted nearly identical remarks, "This Modi, that Modi, everywhere a Modi embroiled in corruption… let's change the meaning of Modi to corruption." (If answers are needed for the selective outrage, Sundar has been a member of BJP since 2020).

Last year, Purnesh Modi, the complainant, strangely sought a stay from the High Court and delayed the trial proceedings. In between, Gandhi amplified his parroting against Adani after the Hindenburg scandal, appearing in Lok Sabha on February 8 with images of Narendra Modi and Gautam Adani on a private jet.

Subsequently, on February 16, Purnesh Modi found some new urgency on how offended he was by Gandhi's comments in 2019. He went back to court to vacate the stay, pleading that "sufficient evidence has come on record of the trial court and the pendency of the present matter delays the trial."

"The pendency of the present matter" remains unexplained as no new evidence has come on record. Still, the High Court lifted the stay, and the case went to trial court, where, interestingly, a new magistrate happened to be. A Supreme Court lawyer wrote in an op-ed that the case itself was a "frivolous complaint, which normally should have been thrown at the threshold." Instead, Gandhi received the harshest criminal sentence in a defamation case, which happens rarely, if at all.

Commentators have argued that the two-year sentence was given with the clear intent of disqualifying Gandhi from parliament. Per the law that governs elections in India, Section 8(3) of the Representation of the People Act, 1951, disqualification of any lawmaker is mandated when "convicted of any offence and sentenced to imprisonment for not less than two years." The math does add up.

Now, the question of the hour is: does this mean that the ruling BJP is threatened by Rahul Gandhi, who they themselves have dismissed for years as an irrelevant, "nepo baby"? Beneath the pace and action, one can infer a need to undermine rivalry from somewhere in the trenches of BJP. But is Narendra Modi himself scared of Rahul Gandhi, a fading figure who has been trying to polish his party image with a 4,000-km trek?

It is hard to believe that the prime minister – who may be fierce, but nonetheless shrewd – would've personally orchestrated a move that risks galvanising unity in the disenfranchised opposition. Opposition parties that have long been antagonistic towards Congress are now coming together in condemnation of Gandhi's disqualification.

What is more plausible is that this attack on Rahul Gandhi was choreographed by officials in the BJP to charm the prime minister, which is even more concerning. It points to a full-blown tyrannical political system, where officials and lawmakers are out there engaging in strategic lawsuits and suppressive, anti-democratic ploys to prove their unwavering loyalty to the leader. And that kind of widespread institutional erosion renders a ruthless political arena where lust of power knows no boundaries, wherein anything is indeed possible.

Gandhi is set to appeal the verdict. Meanwhile, on Wednesday, Nationalist Congress Party lawmaker Mohammad Faizal PP had his Lok Sabha membership restored after appealing to the High Court of Kerala. Faizal was disqualified in January, following his conviction in an attempted murder case with a 10-year jail term. With this recent legal precedence, Gandhi should be able to return. If he doesn't, it will only confirm the political infestation of the legal system, and set the process of the ultimate demise of democracy in the so-called world's largest democracy. We hope not.

Ramisa Rob is a journalist at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments