The Lies We Tell at Funerals

Death has always been there. Over the mountaintops, on the other side of the river, in the room with you right now. You just never notice it. It stands there silently, not watching, but just being. Death has always been, and will always be. You only see a part of it – the human interpretation of it – at funerals.

Nishi didn't see death either, not even at funerals. All she saw were people putting on a facade. Weeping women with dry faces, a funeral conductor prattling on about the deceased when really, all he cared about was the payment he'd be getting. No, funerals were not an honest place, but of course, which place was?

The earliest funeral Nishi could remember was her brother's. They had been a team of five, with three sisters and two brothers, Nishi herself being the second youngest. Except they had never really been a team, had they?

Anyways, there were four of them now. Nishi didn't even know him that well. There was a gap of seven years between them but what she did know about him was not exactly pleasant.

Passing at only eighteen is a tragedy, most would agree. However, what happens when that tragedy is one you model with your own hands? Giddy at receiving his driver's license, Imran had gone on a long drive in his car – so long that he'd never come home from it.

His family later learnt that he had been driving a good measure over the speed limit, and crashed head-first off a bridge. The remains of his body, when taken for post-mortem, reported traces of intoxicants in his system. They were let off from paying any charges, as their father had contacts higher up in the police department. Boys who ended up dead usually complicated things anyways.

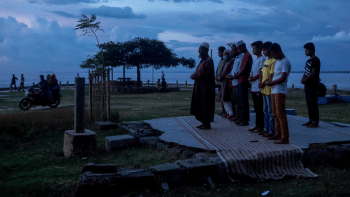

So, he was gone, and while the incident greatly shook the entire family, Nishi and her younger sister were more or less unaffected. They were the youngest after all and had never been deemed important enough to be given enough attention over their ever-egoistic brother. But just like the rest of the women in the family, they adorned themselves with white kameez on the day of the milad and covered their heads with a white cloth as the imam recited verses. After the ceremony was completed, tea was served, and everybody shifted back to their usual spots on the plush sofas.

Then began the pity talk. A distant aunt whom they had seen maybe once in five years shrilled on about what a loss it was, to lose Imran at such a young age. He had been so bright. So full of potential to achieve great things. Everybody nodded their carefully practised faces of sympathy in place. Nishi was ignored, so she slunk off to a corner and contemplated what she was hearing. Imran had never been exceptionally clever, nor did he have ambitions of becoming a pilot or an engineer as the woman was insinuating. So why was she saying those things?

It was then that Nishi realised that the dead were treated in a more dignified manner than the living would ever be. Lies were told in the name of respect – lies spun to be as smooth as silk, lies that felt like honey on your tongue, all because the unknown circumstances surrounding the death were a cause of irrational fear. Speak ill of the deceased and, who knows, maybe they will hear. Maybe they will crawl into your bed at night and take your soul as collateral.

Shuddering away from her suddenly dark thoughts, Nishi nudged her sister's arm and pulled her away to the roof to play. Nishi was eleven. There would be more than enough time for internal monologues in the future.

Rubama Amreen functions with only two working brain cells. Donate a few more at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments