Is unemployment actually declining?

Some results from the 2022 Labour Force Survey (LFS) conducted by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) have been released recently. The survey was long-awaited as it was conducted after a gap of more than five years. But what has been released now is a preliminary report that contains data on a small number of variables. Some observations may, however, be made on the basis of this report.

One important finding of LFS 2022 is a decline in the rate of open unemployment, which the government has claimed to be a positive development. But one cannot come to such a conclusion simply because of the definition of unemployment used and the manner in which the unemployed have been identified in the survey. Although the measure is in line with what is recommended by the International Labour Organization (ILO) and is globally used, it cannot provide the true picture of the labour market in Bangladesh. One was regarded as unemployed only when they did not work even for an hour during the reference week of the survey, was willing to work, and was actively looking for work.

In countries like Bangladesh, where there is no provision for unemployment allowance, poor people cannot afford to remain without work. Hence, it is not surprising that the number of people who didn't work even one hour in a week is so small. In fact, most of the previous labour force surveys in the country showed the unemployment rate to be around four percent. If this is indicative of the real situation of the labour market, that could be the cause of envy for many countries, including the developed ones.

The real situation is that many who don't have access to a good job and are in desperate need of an income try to eke out a living by engaging in some work – whatever its nature is. While the standard measure of unemployment is not able to capture them, many of them are working but poor. What happens to their number and condition is extremely important.

Given the limitations of measured unemployment, alternative indicators of the labour market situation are necessary. Examples include: i) rate of growth of employment in manufacturing, modern services like trade, banks, insurance, and professions like education, health, law, etc; ii) share of the formal sector in total employment (because around 85 percent of employment is in the informal sector); iii) share of regular paid jobs in total employment; and iv) productivity and income in self-employment. What is important is to see if workers are able to move from low productivity sectors to those with higher productivity and income.

In countries like Bangladesh, where there is no provision for unemployment allowance, poor people cannot afford to remain without work. Hence, it is not surprising that the number of people who didn't work even one hour in a week is so small.

However, open unemployment can be a good indicator for the youth, because many of them may have support from family and be able to remain unemployed while searching for jobs. Moreover, they often encounter special difficulties in entering the labour market. As a result, the rate of youth unemployment is usually much higher than the overall average. And Bangladesh is no exception in this regard. The results of the 2010 and 2016-17 LFS show that youth unemployment had increased during that period. Although the preliminary report of the 2022 survey does not provide this figure, recent studies on the topic, especially on the educated youth, do not provide much reason for optimism.

One notable finding from LFS 2022 is a rise in the share of employment in agriculture and a decline in that of industry (no separate data for manufacturing has been provided in the preliminary report). This should not come as a surprise, because since the pandemic started, there have been reports of retrenchments of workers from the manufacturing sector and reverse migration to rural areas.

The number engaged in agriculture is reported to have risen from 24.7 million in 2016-17 to 32.2 million in 2022. How an additional 7.5 million additional people joined agriculture within this period and what its impact has been on per capita income of those engaged in the sector should now become the subject of serious research.

In a country like Bangladesh, where agriculture is still characterised by surplus labour and economic growth is expected to be associated with a transfer of that surplus to modern sectors including manufacturing, a rise in the number and share of people employed in agriculture has to be regarded as a reversal of the process of structural transformation. This reversal is not only an indicator of a difficult economic situation, but also of policy failure.

An apparently positive finding of LFS 2022 is a rise in women's labour force participation rate. But is that indicative of positive development in the labour market or some other development? While a full analysis of such issues has to wait for the detailed results of the survey, one interesting point emerges from the preliminary report: a sharp rise in the figure for rural areas (from 38.6 percent to 50.9 percent between 2016-17 and 2022) and a similar fall for urban areas (from 31 percent to 23.6 percent). In fact, the female participation rate in urban areas has been declining since 2010. While a decline in the participation rate for urban women is worrisome, it would be important to see whether the jump in the rural rate has been helped by rising opportunities or simply due to other reasons, like girls who were out of school during the pandemic doing unpaid family work. Needless to say, research is needed to understand the diverging trends in the participation rates for women in rural and urban areas.

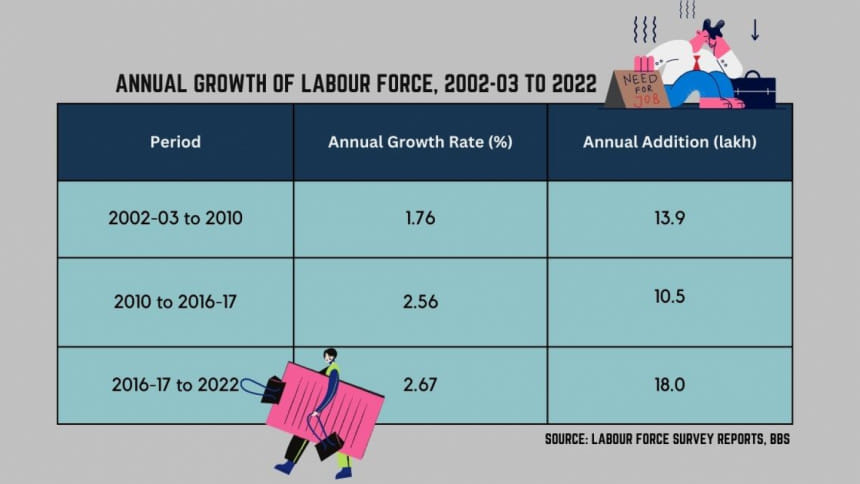

Another riddle that comes out from LFS 2022 is the sharp rise in labour growth between 2016-17 and 2022. Compared to 2002-03 to 2010, there was a decline between 2010 and 2016-17. Likewise, the absolute number joining the labour force every year was also declining. There has been a sharp rise in that number as well after 2016-17. Given the continued decline in population growth, it would have been natural for the earlier declining trend in labour force growth to continue. But the sharp rise after 2016-17 defies rational explanation.

While reliable data are essential for making good policies, it is also important to look at data carefully and examine their causal relationships before conclusions are drawn from them.

Dr Rizwanul Islam is an economist and former special adviser to the Employment Sector, International Labour Office, Geneva. His most recent book is Unnayaner Arthaniti.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments