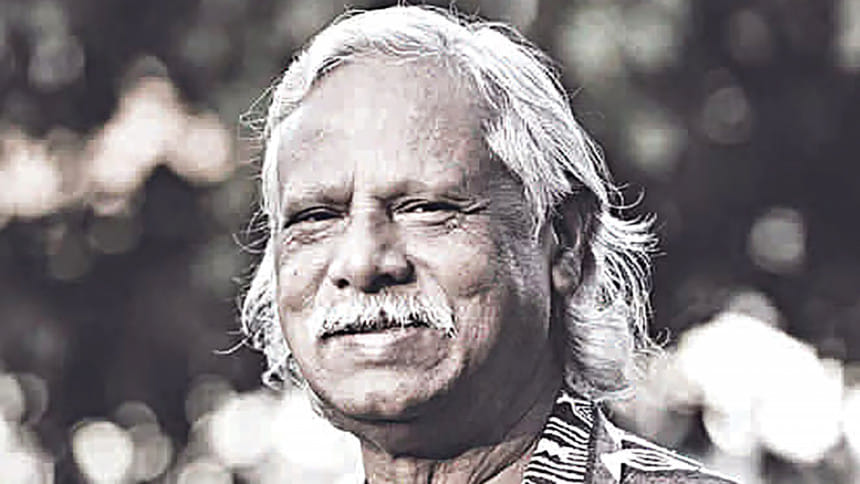

A fighter till the end

Despite his failing health, Dr Zafrullah Chowdhury was more active and hard-working than many healthy persons. Death had knocked on his door several times before. But he kept death away and survived miraculously.

The valiant freedom fighter was born on December 27, 1941, in Chattogram's Raozan upazila. He was the eldest among his nine siblings. He did his matriculation from Nabakumar Institution in Bakshibazar, Dhaka. He passed intermediate exams from Dhaka College.

His life was anything but ordinary. After completing MBBS from Dhaka Medical College in 1964, he went to London to take the FRCS course. He passed the primary exam with flying colours. When the final exam of his four-year course was only a couple of weeks away, the Liberation War broke out in Bangladesh.

In such a situation, an ordinary person would probably have thought that he should take the exam. But Zafrullah thought otherwise. He decided to abandon his academic dreams and dedicate himself to raising public awareness about the Liberation War.

I once asked him how he made the decision to not sit for an exam he prepared for four years.

Smiling, he replied, "I heard about the genocide by the Pakistan army… I thought it was more important to stand by the people, raise public awareness in favour of the Liberation War than to take the FRCS exam.

"Many people were surprised to hear that I didn't sit the FRCS exam. I didn't have to think twice before making the decision. I find it funny that people were surprised at my decision."

At that time, expatriate Bangalees used to protest on the streets of London, holding photographs of the genocide. Foreigners also took part in those demonstrations. In one such protest, Zafrullah tore up his Pakistani passport.

I asked him whether he did this impulsively. He replied, "Tearing up the passport was a protest against the Pakistan army's genocide. I wanted to tell them 'You are killing us, so I am destroying your passport and rejecting Pakistani citizenship'."

In May 1971, Zafrullah and Dr Mobin decided to travel to Kolkata. The two had no passports and citizenship. They collected travel permits and started for Kolkata on a Syrian airlines flight. They had a stopover in Damascus, and trouble occurred there. The Pakistan government was keeping a watch on their movements and tried to arrest them with the help of the Syrian government.

All the passengers disembarked. The two friends, however, didn't get off the flight, sensing danger. They knew that police could not arrest anyone from an international flight.

A Pakistani colonel at the airport claimed, "Two of our citizens are on board. Hand them over to us." They continued negotiations for a long time. Finally, the Pakistani officer was informed that Zafrullah and Mobin were not carrying Pakistani passports. Rather, they were travelling with travel permits. This is how the two escaped arrest.

In late May, the two reached Agartala which was under sector-2 of the Liberation War. Zafrullah built a field hospital there. This hospital ultimately became Gonoshasthaya Kendra in the independent Bangladesh, which primarily took shape in Bisramganj village of Agartala.

Khaled Mosharraf, sector commander of sector-2, was running the war from that region. Injured freedom fighters were treated at that hospital named "Bangladesh Field Hospital". The hospital, made of bamboo and hay, had 480 beds and an operation theatre. Complicated surgeries were conducted there to save the lives of the badly injured freedom fighters.

The hospital was the brainchild of Zafrullah and Mobin, the only cardiac surgeon of Pakistan at the time. They trained a group of volunteers as paramedics who worked as nurses. Rights activist Sultana Kamal was one of the nurses.

When the hospital was about to be set up in Bangladesh, objections were raised from the administration. Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, then president of the newly independent Bangladesh, heard about it. Zafrullah met Bangabandhu at the Secretariat. He recalled what Bangabandhu had said to him that day.

Zafrullah said to Bangabandhu, "Mujib Bhai, no permission is being given for Bangladesh Field Hospital."

"Actually, when the word 'Bangladesh' is there, it gives the impression that it's a state-run hospital. Choose a better name for the hospital," said Bangabandhu.

After a lot of arguments, Bangabandhu said, "You choose three names and I will pick three more. Then we two will select the best name for the hospital."

Zafrullah then chose three names and got back to Bangabandhu.

Bangabandhu inquired, "What name did you choose?"

Zafrullah said, "The first one is Bangladesh Field Hospital and the second option is Gonoshasthaya Kendra."

Bangabandhu stopped him and said, "Gonoshasthaya is a beautiful name. This will be the name of your hospital. It will not only provide medical treatment, but also will contribute to building the nation. Gonoshasthaya Kendra will have to work in the education, agriculture and health sectors as well."

Zohra Begum, MA Rob, a joint secretary of the Pakistan government, and Dr Lutfor Rahman donated five acres of land from their family estate at Savar. Bangabandhu acquired 23 acres and donated it to the hospital. The Bangladesh Field Hospital, which served during the Liberation War, started its journey as Gonoshasthaya Kendra in independent Bangladesh in 1972.

It is an organisation of the people. Zafrullah challenged the stereotypes against women and initiated women empowerment in his organisation. He trained women as electricians, carpenters, welders -- jobs traditionally done by men.

Gonoshasthaya Kendra employed female drivers who used to drive jeeps on the Dhaka-Aricha highway in 1982. The total number of its staffers is around 2,500, and 40 percent of them are women.

Zafrullah managed to continue his work even though his kidneys were failing. He had to undergo dialysis thrice a week. It is an expensive treatment in Dhaka and elsewhere in the country. Gonoshasthaya Kendra now provides dialysis service to more patients than all government and non-government hospitals combined.

Zafrullah built a 100-bed modern kidney dialysis centre at Gonoshasthaya Nagar Hospital. He used to say that this is the biggest dialysis centre in Asia and it's more developed than those in any other countries. It charges patients very little for this service.

Zafrullah's most remarkable contribution after the Liberation War was formulating the drug policy. The pharmaceutical market in independent Bangladesh was entirely controlled by the multinational companies. There were around 4,000 drugs in the market at that time, many of which were nonessential. Some of the medicines were produced locally and the most had to be imported.

Immediately after independence, Zafrullah dreamed of building a local pharmaceutical industry. He talked to Bangabandhu about this matter. Bangabandhu agreed with the proposal of importing medicines from socialist countries at discounted prices.

He also convinced former president Ziaur Rahman about the importance of developing the pharmaceutical industry. Zia wanted him to join his cabinet and work on a drug policy. But Zafrullah rejected the offer as Zia had anti-liberation persons with him. He clarified his position in a four-page letter written to Zia.

Zafrullah later convinced HM Ershad and ultimately formulated the drug policy. Out of the 4,500 drugs available in the market back then, 2,800 were banned.

Establishment and expansion of the local pharmaceutical industry are the outcomes of that historic policy. Now 95 percent of medicines needed for more than 170 million people of the country are produced locally. Bangladesh also exports medicines now.

Zafrullah is criticised for keeping on good terms with the dictatorial governments of General Zia and Ershad. It is not untrue. Is Zafrullah the only person who maintained a good relationship with Zia and Ershad?

Through these relationships, Zafrullah did something for the country. Nobody can accuse him of using these relationships to serve his own interest.

Many people and some newspapers say that Gonoshasthaya Kendra is owned by Zafrullah. But the fact is, Zafrullah is the founder of the organisation, not the owner. He has no right in its property. No individual can claim its ownership either. The organisation is owned by the people of Bangladesh.

Zafrullah was awarded "Swadhinata Padak" -- the country's highest state award. He is also a recipient of the Ramon Magsaysay award.

His hospital doesn't look like a posh five-star hotel. It provides treatment to the poor at nominal cost.

Throughout his life, Zafrullah did what he thought to be right. He never thought about the consequences of his actions.

At the beginning, I gave some ideas about Zafrullah's lifestyle in London. After the Liberation War, he radically changed his lifestyle. He would wear clothes until they were absolutely worn-out.

One day I asked him about this habit. Pointing to the shirt he was wearing, he said, "This shirt is 30 years old. It is still in good shape. Why should I change it?"

Zafrullah's Bangladesh Field Hospital served during the Liberation War. He is not physically present amongst us anymore. However, his organisation is with us and it will be here for a long time. The physician will remain alive lovingly in the hearts of the people. And, it is the people who will keep Gonoshasthaya Kendra alive forever.

[This article has been translated into English from Bengali by Md Shahnawaz Khan Chandan.]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments