Boats against the current: Reconciling the Dhaka of old with the new

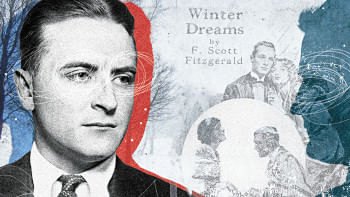

Nadeem Zaman's The Inheritors retells and recontextualizes one of the most famous stories there ever was—F Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby (1925). In Zaman's novel, the Jazz Age is transmuted into modern day-Dhaka, the familiar idols of Gatsby, Daisy, and Nick Carraway, becoming Gazi, Disha, and Nisrar Chowdhury. These obvious signposts can be less than welcome, but there is an evident care in the writer's adaption of his source material, even when The Inheritors strays further and further with subplots and subtexts of its own.

Zaman's greatest success moreover is his understanding of the most pivotal of elements in reading Gatsby: the mystery. In both novels, the truth is ever receding—just from arm's length—not revealed until chapters on end. Zaman's novel, too, is at its best when the reader is left wondering, even those well-versed in the Fitzgerald novel.

In The Inheritors, the narrator, Nisrar, is thrust back into Dhaka from his home in America on matters of property dealings. The best offer on the table is from the elusive businessman Junaid Gazi, who strangely wishes to purchase all of the properties, namely that opposite to the home of Disha, Nisrar's first cousin. Fans of The Great Gatsby will surely know why. Here, though, Gazi and Disha are not just ex-lovers but ex-spouses, and the dynamics of the much-analyzed love triangle isn't centered at the Gatsby of the story but Daisy—who Nisrar very often admits to having a crush on. Wondering if the new novel ends the same as the old is ostensibly The Inheritors' main hook.

Where the book may lose readers, however, is the narrator's conflicts pertaining to identity, home, wealth, and privilege—all of which are much more text than subtext in Zaman's writing. Despite starting strong, the novel makes the conscious choice to forego richer storytelling in favour of class and social commentary. This is unfortunately filtered through the eyes of expat Nisrar, who routinely exhibits an above-it-all attitude to upper class lifestyle. He will also remind us he's one of the good ones, who hands CNG drivers and kids on the street 500 or 1000 taka notes.

The narrator's characterization, it feels, is that of a Mary Sue, a too-perfect man who routinely receives compliments like "You're damn smart" or "Always the funny guy" or "Good looking, smart. You know there are women here that would tear you apart like that." The only flaw ever mentioned of Nisrar is his history of infidelity—a masculine ideal of a flaw.

His love interest, Jasmine (the stand-in for Gatsby's Jordan), almost immediately takes to Nisrar, without any convincing flirtations or palpable spark. Jasmine is always seen with doe-eyes, pining for Nisrar, who never truly returns her affections, preoccupied ever with something else. Substituting the homoeroticism of the 1925 novel with Nisrar's incestuous feelings for his cousin is an interesting choice, but it doesn't jump off the pages.

The Inheritors, ultimately, is more interested in exploring Dhaka history and life, at least as seen by a foreigner. Some of its outsider-looking-in description of the city sound delightfully alien (when was the last time you heard someone say "Kemal Ataturk Avenue" in full, or utter a phrase like "Bashundhara City, one of Dhaka's premier housing developments"?) But then the narrator will also make presumptuous generalizations, like assuming the 2016 Holey Artisan attack to be our 9/11, which simply doesn't translate. These musings start to grow tiresome, given the way in which the narrator speaks on the matters with what feels like authorial intent.

Zaman's book shares most of its themes with The Great Gatsby, but these threads are mostly left unresolved. No doubt paralleling the life of an immigrant, whose life forever is one of in-between, there is a lack of satisfactory conclusions—a neat bow to tie things together like in Fitzgerald's writing. This conscious choice on the writer's part does leave the reader wanting, though, and makes one question the need to so closely reattribute the Jazz Age tale for this particular novel.

It is a testament to Nadeem Zaman's writing, of course, that each chapter and passage flows as well as it does. His prose has a calm and self-assuredness to it that keeps the reader hanging on every page. The Bangladesh-born author's ambition for The Inheritors, for its ups and downs, brings to mind Jorge Luis Borges' "Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote" (1939), a metafictional short story which supposes that even if one writer were to re-create, word-for-word, a famous work of the past, the exact duplication would still be a rich text worthy of its own analysis. The same novel would be entirely unique—because the time and circumstances have changed since, and no two authors could be the same.

Mehrul Bari S Chowdhury is a writer, poet, and artist. He received his MA in Creative Writing with distinction at the University of Kent in Paris. He has previously worked for Daily Star Books, and is the editor of Small World City.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments