The global conspiracy – against women

When I read that countries led by women had "systematically and significantly better" Covid -19 outcomes such as earlier lockdowns and much fewer deaths compared to countries led by men, it wasn't such a great revelation. Women are crisis managers by nature – just see how our mothers respond to any sickness in the home or when the family is faced with a calamity. But I was pleasantly surprised that researchers had bothered to gather empirical evidence to prove that women did a better job than their male counterparts in dealing with the pandemic and that it was broadly reported in the media. Let's face it, we rarely get thanked for any of the work we do to keep the world – yes, the world – running.

This is because a) we live in an obstinately patriarchal, capitalist world where women are kept in the lower rungs of the hierarchy; and b) our unstinting nurturing and persevering is taken for granted and considered part and parcel of our role in society.

If anyone deludes themselves into thinking that this is old news and applies only to the "backward", "poor" or Muslim-majority countries, please think again. Stereotypes of what a woman should be like and how capable she is are alive and kicking all over the world. This is not just a "typical woman's rant". This is actually the conclusion of a massive survey by the United Nations Development Programme's (UNDP) Gender Social Norms Index, which has found that, globally, almost 90 percent of men and women (unfortunately) have fundamental biases against women.

So, half the people (both men and women) of the world still believe men are better political leaders and 43 percent think men make better business executives. If you think this is alarming, get this: more than one out of every four people believe it is justified for a man to beat his wife, according to this survey. Now, does it not makes sense why the boardrooms across continents are predominantly filled with men and why one in six women in the US has been sexually assaulted or raped as a child or adult?

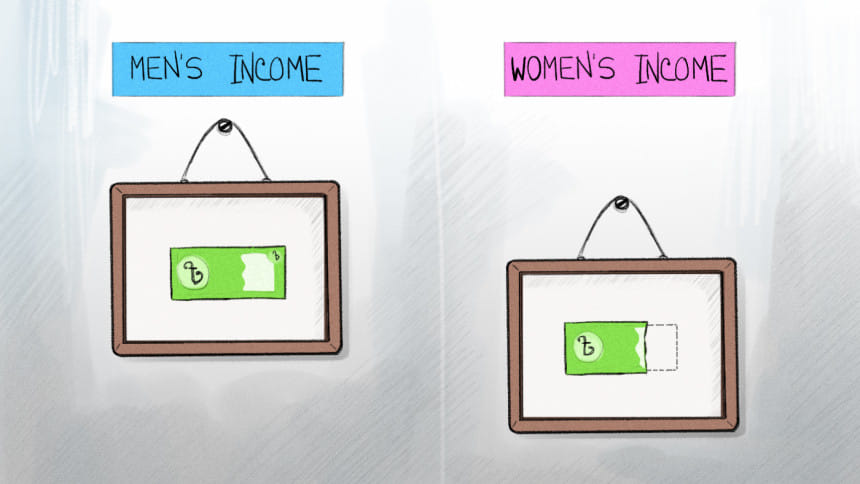

And let's come to the biggest area of discrimination: the amount of money we get compared to men for the same work, using the same skills, and putting in the same number of hours. A female labourer carrying the same number of heavy loads at a construction site in Bangladesh working the same hours gets much less than a male labourer. Ironically, this applies to a woman vice-president of a multinational company, a woman broadcaster at the most popular international broadcasting company, and even a top-ranking female actor in Hollywood.

The UNDP report has found that even education has not been able to reduce the income gap. Over the decades, many countries have adopted policies that have successfully reduced gender gaps in education – higher enrolment of girls and more women with advanced education degrees – but women are still not getting the expected economic opportunities: "Even in the 59 countries where adult women are more educated than men, the average income gap is 39 percent."

So, in the era of uber-technological-advance (maybe ChatGPT is writing this tirade) and progressiveness, how is this irrational practice of unequal pay still thriving? Clearly, deep-rooted biases and stereotypes are at play. UNDP's report refers to a "child penalty" that is at work and that arises from the social expectation that women devote more time to childcare than men.

It's about time we change this social expectation. Men should not be applauded and made a fuss over when they take on household chores or look after the kids while Mommy is running a company or has to go on a business trip. Sharing all those tedious tasks of figuring out what to cook for dinner, helping with the homework, or buying Eid clothes for the household staff should be routine activities for men as well. Once we have been absolved of the guilt of "neglecting" the home because our partners are taking care of it, chances of us getting the same pay as our male colleagues will be higher.

While this may be the ultimate income equaliser, there are cases where, even when the organisation recognises the worth of a female employee's work, they may still pay her less – mainly because they can get away with doing so. Most women don't know what their male counterparts are getting and many are too embarrassed to speak up about it even if they do. Women, moreover, seldom bargain for a raise or promotion. So it is up to the employers – male or female – to ensure that there is no discrimination in pay between men and women employees with the same credentials.

But what about politics? Why is it that only 10 percent of heads of state are women and 22 percent have ministerial posts? Again, it is a question of perception and social norms. Which is why there are so many women at the highest seats of power (member of parliament or prime minister) in countries such as Sweden, Slovenia, and Norway with lower biases or gendered social norms.

Bangladesh seems to be quite a conundrum when it comes to political empowerment. We have had a woman in the highest seat of power for the last three decades and dozens of women ministers, along with the selected 50 seats for women members of parliament. Clearly both men and women in Bangladesh are quite comfortable about having a woman at the highest seat of power, something that is not present even in some of the most advanced countries. But when it comes to women in local government (in Bangladesh), even for the few who are elected, their power and resources are nowhere near that of their male counterparts. Gender biases and social norms are at play here, creating roadblocks for women politicians at the local government level.

Overriding all these impediments to realising our potential is violence, which is a direct consequence of this secondary status of women. Violence is used to "control" women and keep them in their place. In Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan, the high rates of sexual and physical violence against women and girls are a result of this desire to keep women oppressed. In these countries, age-old cultural norms have been incorporated into religious practices, thus accentuating the secondary status of women and emphasising their role as primarily mothers and homemakers. Often, religion is conveniently interpreted to deprive women of employment, financial independence, and education, and prevent them from escaping violence. Thus, despite the efforts of governments to adopt pro-women policies, a patriarchal culture and interpretations of religion dominate and nullify endeavours to empower women. In Bangladesh, despite its advances in enrolment of girls in schools, there is a high dropout rate at the secondary level because many female students are married off early as child marriage is a part of our cultural norms.

There is enough empirical evidence from all over the world to show how a society benefits when women are granted equal rights and equal access to opportunities. Women bring to the table greater empathy, communication skills, ability to endure and survive the most devastating realities; they are good at diffusing conflict, they are more intuitive, and great at crisis management. In a world that is haunted by apocalyptic fates due to uncontrolled climate change, unrelenting pandemics, and constant armed conflicts that massacre millions of people, it is time men shoved aside their irrational fear and let the women in – to share both their burden and their power. It is the only way to heal the battered, wounded world we live in.

Aasha Mehreen Amin is joint editor at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments