‘Health services deeply troubled by corruption, lack of accountability’

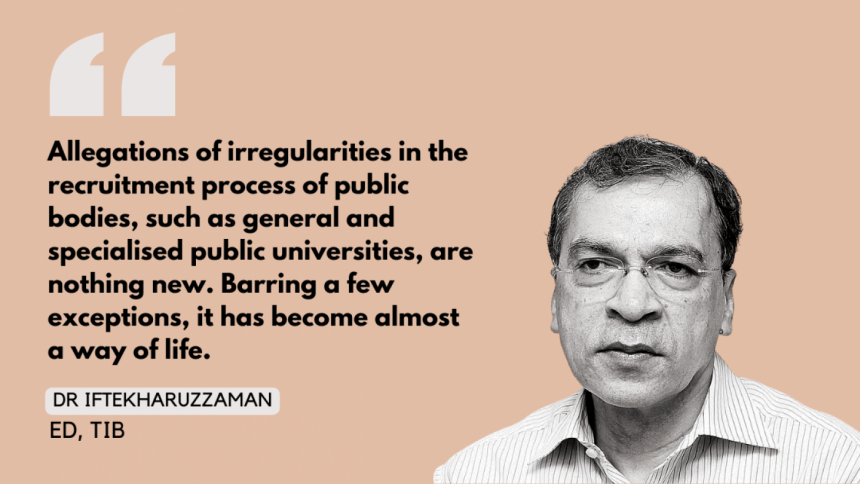

Dr Iftekharuzzaman, executive director of Transparency International Bangladesh (TIB), talks about how corruption and a lack of good governance have crippled the country's healthcare services, and what needs to be done to overcome the challenges facing this sector, in an exclusive interview with Naznin Tithi of The Daily Star.

Recently, there have been allegations of irregularities in the recruitment process of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University (BSMMU), specifically against its vice-chancellor. Although the health minister said the allegations would be looked into, we still do not know of any action being taken by the government. What could be the reason behind this?

Allegations of irregularities in the recruitment process of public bodies, such as general and specialised public universities, are nothing new. Barring a few exceptions, it has become almost a way of life. According to credible research and investigative reports, the main factor behind the wide prevalence of such irregularities is the lack of both preventive and corrective measures against partisan political influence, nepotism, favouritism, and various types of illicit payments – which have been allowed to be institutionalised violating the relevant rules.

The BSMMU corruption recently revealed by several evidence-based media reports represents the typical ball game of the recruitment business. It is disappointing that recruitment at such a premier institution, dedicated to advanced health education and medical services, is bedevilled by so many irregularities and a lack of accountability. But it is not surprising at all, because the rot is allegedly at the highest levels, which means they enjoy unlimited impunity due to partisan political connections. This not only accounts for inaction against various forms of abuse of power, but also indiscriminately compromises fundamentals of due process, accountability mechanisms, and institutional integrity.

Some recent incidents have also exposed the lack of accountability and ill practices prevailing in private healthcare facilities. The tragic death of a mother and her newborn (the latter in the capital's Central Hospital) is a case in point. How can we hold private healthcare facilities accountable?

Like any other public service delivery sector, health services are deeply troubled by corruption and lack of accountability. The sector has always been starved of resources due to one of the lowest rates of budgetary allocation by the global standards. More importantly, even the comparatively meagre resources are subjected to various forms of corruption, misappropriation and misuse, procurement fraud, extortion, and swindling. As the health sector was exposed to sharper spotlight after the onset of the Covid pandemic, the long-nourished anomalies in the sector were more graphically exposed, accompanied by evidence of how the pandemic became a blatant profit-making opportunity for some patronage-rich, vested quarters.

A frustrating picture of governance deficit and corruption was recently revealed by a study conducted by TIB on the Holy Family Red Crescent Hospital. The findings were particularly disappointing, given the hospital's glorious history as a service provider carrying the International Red Cross and Red Crescent brand, no less.

Similar revelations have come to the fore through earlier TIB research conducted on both public and private health sectors. The private sector has agreeably filled a significant gap of health service facilities against a growing demand, which the public sector is justifiably unable to meet. Regrettably, due to a lack of specific legal and regulatory framework – and more so, in the absence of any strategically designed road map towards achieving health service excellence – the private health sector has witnessed mushrooming growth, with the almost-exclusive motive of making profits.

Professional expertise, experience, and excellence have been undermined to allow private health businesses to flourish on power drawn from money, fraudulence, and connections. The much-talked-about Regent Group's collusive fraud to extort public money in the name of providing health services during the Covid crisis, without meeting the minimum basic requirement of having a licence, is no isolated event. It is common knowledge that the overwhelming majority of private healthcare establishments do not meet the minimum level of professional skills, equipment, and facilities.

Again, there are definitely some exceptions. But the private health sector has been captured by unscrupulous hospitals, clinics, and diagnostic centres all over the country, creating a thriving business sector that is based on extortion, fraud, and various other illegalities, and non-compliance of whatever regulations or policies that exist. All these have rendered quality health service in Bangladesh a pipe dream. The Central Hospital story is just an example of a frustrating state of health rights and security.

The High Court recently observed that corruption has permeated every level of the health sector. It has also criticised the Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC) for not playing its role.

This is not the first time that the High Court has made such observations about corruption and the role of ACC. The court's concerns over health sector corruption and its doubts about ACC's role provide a judicial validation for a prevailing trust deficit about whether the commission is effective in delivering its mandate, especially when the "big fish" are involved.

To be sure, ACC has its own limitations. Those with power in political and governance spaces have not fully come to terms with the concept of an independent, specialised corruption control body. This is manifested by a history of legal amendments and administrative actions taken to curtail its powers. The ACC itself hasn't always shown the courage or capacity to exercise whatever legal and institutional capacity it has been endowed with, without fear or favour. Effective delivery of the ACC mandate, therefore, demands changes of mindset and actions within the commission and beyond.

TIB has been working for long to unearth the ill practices in our health sector and has also given some recommendations to change the situation. What happens after the TIB reports are published? What kind of reforms are needed to heal our health sector?

Indeed, TIB's work on health sector corruption, as for any other sector, is aimed at catalysing positive changes on legal, institutional, policy and practice levels through its research and knowledge-based engagement and advocacy with stakeholders (including government and other relevant authorities). Every report we publish is transformed into policy briefs containing specific recommendations for change, using which we reach out to the authorities and try to push for actions, which often result in fruition. I would not say that we have been able to control corruption as such, which is not our mandate anyway. But as a demand-side actor, we have in fact been able to contribute to build stronger potentials of the state to control corruption through numerous new or amended laws, policies, institutions, and strategies. Regrettably, the problem remains in enforcement and implementation. We bring the horse to water; whether it will drink or not depends on itself.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments