What good will nationalising all secondary schools do?

Non-government secondary school teachers have been demanding the nationalisation of schools for a long time. That the schools as well as the teachers should perform better and the conditions for doing so have to be created is not in dispute. Is nationalisation, that is, bringing all schools under government management and making teachers national government employees, the answer?

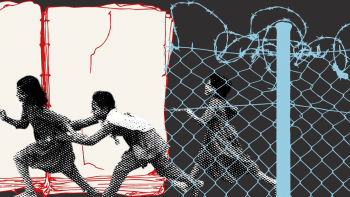

Teachers have been carrying out sit-ins in front of the National Press Club and being subjected to coercion by police to restrain them. This is a sight we can do without. The meeting of the protesters' representatives with Education Minister Dipu Moni is reported by the teachers' spokesman to have been not "fruitful." The minister said no decision can be taken before the upcoming national parliamentary election, but promised to appoint two committees, respectively, to look into "how nationalisation may be undertaken" and its "financial implications." Teachers vow to continue their protest.

The protesting teachers' demand to be placed on the government employees' roll and to be remunerated as per civil service salary and benefit rules, on the face of it, may be seen as legitimate. Teachers' well-being is important, but the stakes are much higher. Teachers' welfare has to be protected along with solving the problems of the woefully low quality, inequality of opportunities and exclusion of various disadvantaged groups. Expenses on teachers amounts to over 80 percent of the operating costs of schools. How well teaching personnel cost is managed largely determines the return from the total education investment of the nation.

There are over 20,000 secondary schools in the country, of which only 684 are managed by the government directly, all of which enrol about 18 million students. The non-government schools (other than a few privately owned schools, many of which are English-medium) receive government support through MPO (Monthly Pay Order), an arrangement to pay basic salaries by the government of approved numbers of teachers. The system originated in the colonial days, when the rulers declined to take responsibility for children's education and instituted the system of meagre grants-in-aid to schools established by community initiative and philanthropy.

Independent Bangladesh has taken responsibility for free and compulsory education at the primary level (up to Class 5) by adopting the compulsory education act in 1990. No such obligation has been assumed by the government for secondary or tertiary education. Without belabouring the point, it can be said that a developing country aiming to gain middle-income status in a decade and aspiring to be a developed country by 2041, cannot leave a large proportion of its youth deprived of secondary education of acceptable quality. Goal 4 of the global Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 2030) aims for free, inclusive, and quality secondary education for all children. Bangladesh has accepted this commitment. But it has not worked out a plan and strategy defining the scope of government obligation, including public funding commitment. This is what Dr Dipu Moni may be talking about when she says two committees will work on the "nationalisation" approach and its financing.

Looking at the issues though a broad frame, rather than just repeating the pattern in primary education that has not worked well, is necessary.

We need to learn from the experience of primary school nationalisation. It's not exactly a resounding success, despite official narratives being to the contrary. In over three decades, we have not achieved universal inclusive and equitable participation, especially if one considers children actually completing this stage. Even more disturbing is the result in learning outcomes. By the World Bank's learning poverty metrics, 58 percent of children in Bangladesh between 10-14 years of age cannot read a simple Bangla text comprehensively. It cannot be a consolation that our neighbours in South Asia are not doing much better. The point is that nationalisation has not delivered the results, though the teachers' remuneration has improved somewhat. Primary teachers do complain about anomalies about the salary structure in which they have been placed, compared to civil service positions in other sectors.

A nationalisation plan for secondary education in line with what has been done for primary schools (which apparently is the demand of the protesting teachers) will not serve the children's and the nation's interest. And ultimately, it will not help to improve the welfare and status of teachers.

Fulfilling the state's obligation to guarantee the right to basic education, now universally defined as pre-school to pre-tertiary (K-12), need not and should not be an issue of scarcity of public funding. Many countries poorer have invested larger public funds in education than the less-than-two-percent-of-GDP of Bangladesh. It is a question of national priority and political commitment. But, at the same time, it has to be ensured that the funds are used effectively to achieve the results.

Basic structural problems of education governance and management, including the performance of teachers and their status in society, have to be considered. Looking at the issues though a broad frame, rather than just repeating the pattern in primary education that has not worked well, is necessary. Education discourse, research, advocacy of education activists, and relevant international lessons suggest key areas which need policy-level attention.

1) Decentralising the education governance to plan and manage quality education in each upazila and district, and ensuring greater accountability of schools and teachers to the parents – eventually creating district school authorities to run quality schools in each neighbourhood.

2) Attracting and retaining the best talents in school teaching, with necessary steps taken for professional preparation, certification, professional career path, incentives, and social status. A national education service cadre and a separate education service commission would also be important measures.

3) A regulatory framework for all schools and all teachers (government and non-government), applying basic school and teacher quality and performance standards.

Working on these issues calls for a longer-term commitment at the highest level of policymaking. But these are perhaps not the concerns high on the list of the protesting teachers. An appropriate strategy would be to consider short-, medium-, and longer-term actions within an overall frame of goals, principles, and strategies. While transformative and ambitious changes are envisaged and initiated, children have to attend school, and teachers have to teach. Therefore, interim and transitional measures have to be considered, being careful not to pre-empt larger reform.

A vision for change in basic education (primary and secondary) has to be shared with teachers and their leaders. The message has to be conveyed that the vision cannot be realised without teachers joining the journey. Meanwhile, some of their grievances can be addressed with the assurance to modify MPO payments as needed, including raising salaries and benefits. This message of vision, shared journey, and interim steps to be taken would be best delivered by the prime minister to inspire confidence among teachers.

Dr Manzoor Ahmed is emeritus professor at Brac University, chair of Bangladesh ECD Network, and vice-chair of Campaign for Popular Education. Views expressed in this article are his own.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments