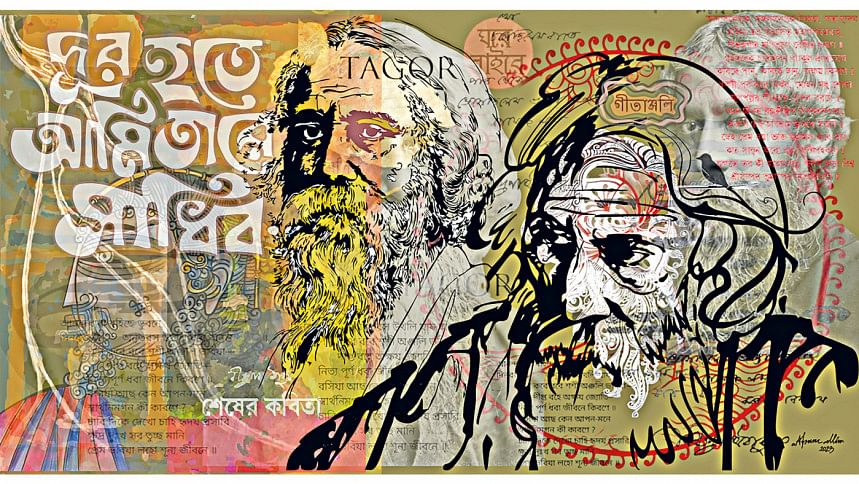

Rabindranath Tagore’s ‘Gora’: From notions of purity to an all-embracing Bharatborsho

Rabindranath Tagore's Gora, written between 1907 and 1909, reveals the ways in which Tagore addresses the all-important issues of his time—national identity formation, the coming together of people over time, and obstacles or barriers put in the way of the progress of a nation. The novel captures Tagore's fascination with envisioning a future based on human amity or moitri, one where the powerless and the dispossessed transcend the barriers of division and distrust.

A good way to think about Tagore's novel from these viewpoints is to consider the title of his novel, for it evokes three Bengali words simultaneously. Primarily, and the way the word is spelt in the Bengali original, to be "gora" is to be fair-complexioned or even a white man or woman, and a European to boot; however, the word is also related to a homonym implying "root", or "foundation" or "origin'. The deftly chosen word is thus especially apt for the novel since its titular protagonist is revealed to be an Irish orphan abandoned and then rescued during the Indian Mutiny of 1857. Named Gora since he is fair-skinned, the protagonist is nonetheless in a quest to go back to the roots of Indianness and preserve and perpetuate the founding values and unity of his "Bharatvarsha". But a third similar sounding word, albeit inflicted by a nasal sound in Bengali, tells us that it can also be someone who is a blind follower of his faith and even fanatic about it. All three words are relevant to Tagore's Gora and the narrative that Rabindranath creates, for he presents not only an apparently fully Indian Bengali protagonist who paradoxically turns out to be a European white person by birth, but who had become a fanatic about Hinduism and intent on establishing it in its purest form in 1870s India. He is, of course, ironically oblivious of his origins till he learns about it at the end of the novel, and had overlooked till then the many streams that had poured into the river of Indian civilisation but is visible to orthodox Hindus of his time as only one mighty body of water flowing through the course of subcontinental history.

Tagore seemed to have realised that the earlier Indian Bengali champions of nationalism had been too complacent in this regard. Also, to achieve collective nationhood for the people of the subcontinent as a whole would require overcoming racial, religious, and caste prejudices as well as the elimination of at least some of the barriers women were facing in trying to join men in the movement to create a radically transformed and lot more egalitarian society in Bharatvarsha.

Although the setting of Gora is mostly in and around colonial Calcutta in the seventh decade of the 19th century, it is important to note that it is a novel that could only have been written after Bongobhongo or the 1905 partition of Bengal, which was clearly part of Britain's colonial policy to "divide and rule" the resurgent province. The short-lived division of Bengal had immediately led to the Swadeshi movement that Rabindranath had championed creatively and energetically for a few years, only to be quickly disillusioned by what he perceived to be its excesses, and by the divisiveness he felt it was creating in his country. He had rued its excesses subsequently and underscored it as the kind of nationalism to avoid. He would write against such nationalism—whether in India, or Japan or the West—in outspoken and even hectoring fashion in later years after he had seen the manifestations of its ugly side not only during the later years of the swadeshi movement but also just before, during and after the First World War.

To illustrate these points, one may cite a few passages from his third lecture of his 1917 lecture tour to Japan and the United States, "Nationalism in India". The positive thing he has noted about the subject, he tells his American audience while delivering the lecture there, is that he found "a parallelism exists between America and India—the parallelism of welding together into one body various races". But he is convinced by now that nationalism has also become a "great menace," for in India too he feels "it is the particular thing which for years has been at the bottom of India's troubles". Tagore feels that the 'caste system' and burdensome traditions have been imperiling India in his own times. Instead of such things that lead to divisiveness he would like to see "social cooperation" as the basis for both the east and west to move forward internally and externally.

Gora illustrates all these issues in the course of its 500 or so pages. On the one hand are people in it like the protagonist, idealistically representing those who would like to see Hinduism flourish throughout the land in its pristine form, unlike the other Hindu zealots of the novel who espouse the Hindu cause but without his humanity. On the other hand, reformist Bengali Brahmo zealots would like to see a faith without some of the Hindu ritual practices that they claim would make it similar to the religion that existed in their land in its original form. But from time to time, we glimpse people of other faiths such as Islam that has spread in the subcontinent, but that seemed to have been shut out of any consideration in the tussle between the supposedly orthodox and the professedly reformist versions of Hinduism professed by the Hindus and the Brahmos of the novel respectively. Gora's Bengal, then, is an area of ideological skirmishes, misunderstandings, and aggressive proselytising by some zealots at the expense of the silence, backwardness, and lack of power of the silent majority. All this, moreover, is taking place at a time when the British have further consolidated their power after silencing Indian protests against their rule, seemingly decisively in 1857. By the 1870s, as depicted in the novel, at least a few "babus" had taken their sides! But American transcendentalism is also a presence in the novel and we have references to the work of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Theodore Parker and other transcendentalists as influences on at least a few of the open-minded Brahmo characters.

A good way to think about Tagore's novel from these viewpoints is to consider the title of his novel, for it evokes three Bengali words simultaneously. Primarily, and the way the word is spelt in the Bengali original, to be "gora" is to be fair-complexioned or even a white man or woman, and a European to boot; however, the word is also related to a homonym implying "root", or "foundation" or "origin'.

It is not necessary to dwell here on the religious divide between the Hindu and Bhramos as depicted in Gora in any detail since this has been dealt with well by earlier critics who have also pointed out Tagore's critical treatment of the religious bigotry, racial prejudice, and casteism evident in Gora's world, as well as English contemptuous treatment of the natives of the land they had taken over. But what can be emphasised now is Tagore's awakened sympathies for the Muslims, ordinary Indians, and women's lot as depicted throughout the novel. His field level experience in East Bengal at the end of the nineteenth and the beginning years of the 20th century and first hand encounter with the excesses of some of the Swadeshi movement activists as far as Muslims were concerned, as well as disillusionment after witnessing the tendency of the movement to take violent turns, and his increased sensitivity to the way women were being treated as inferior people by his own people, were bothering him now. He felt that such things needed to be remedied for the coming together of peoples. Tagore seemed to have realised that the earlier Indian Bengali champions of nationalism had been too complacent in this regard. Also, to achieve collective nationhood for the people of the subcontinent as a whole would require overcoming racial, religious, and caste prejudices as well as the elimination of at least some of the barriers women were facing in trying to join men in the movement to create a radically transformed and lot more egalitarian society in Bharatvarsha.

In the opening page of the novel, we encounter not only bird songs, but a baul or mystically inclined wandering minstrel singing about the achin pakhi or unknown bird flitting "in and out of the cage" eluding even the attempt of the lyricist to "chain it" with his heart. That is the kind of free, borderless space he is proposing symbolically as the landscape he would like to project ideally in the course of the novel. At the end of it, and after Gora finds out that he is not a Hindu at all, since he discovers he was actually an Irish foundling, he realises that he need no longer be afraid of "becoming a fallen person and losing my caste status". Gora feels that he no longer needs to be troubled by apprehensions created by "an untroubled, unblemished image of Bhasratvarsha", that he is now freed from "from an impenetrable…imaginary fortress", and he can delight in having "arrived at the heart of a great reality" where he can serve his people. The great thing for Gora at the end of the novel is that he believes that he has now become truly a citizen of a land where he need not feel any "hostility towards any community, Hindu, Muslim or Christian". He can now "belong to every community of Bharatvarsha", having "become so pure that even in a low caste chandal's home I will no longer be afraid of sullying myself".

Partha Chatterjee mentions Rabindranath Tagore only twice in his excellent diagnosis of the pitfalls of nationalism, The Nation and Its Fragments (1993), but one of these references is his very acute comment on the works of Rabindranath Tagore in "his post-swadeshi period". Chatterjee argues that Tagore at this point of his life and writings was intent on writing the nation from the newly found perspective of someone who saw that "the true history of India" was "in the everyday world of popular life whose innate flexibility, untouched by conflicts in the domain of the state, allowed for the coexistence of religious beliefs." That Tagorean perception fashions the trajectory of his novel and makes it so very relevant to our contemporary moment.

This paper has been edited for brevity. It was first presented virtually at Gauhati University as part of their Distinguished Speaker series. It was later published in their journal.

Fakrul Alam is Supernumerary Professor, Department of English, University of Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments