The many meanings of Partition 1947 and beyond

- My memory is again in the way of your history - Agha Shahid Ali

- The fact that it is now forgotten does not mean that it does not extend into the present - Walter Benjamin

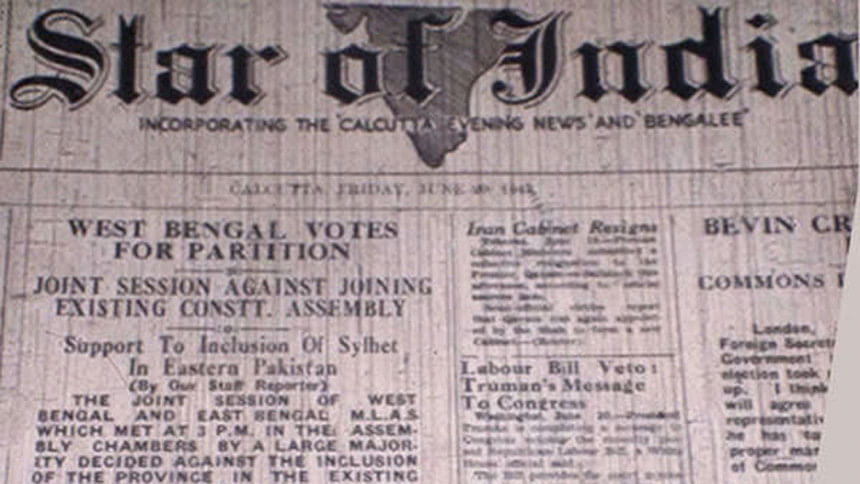

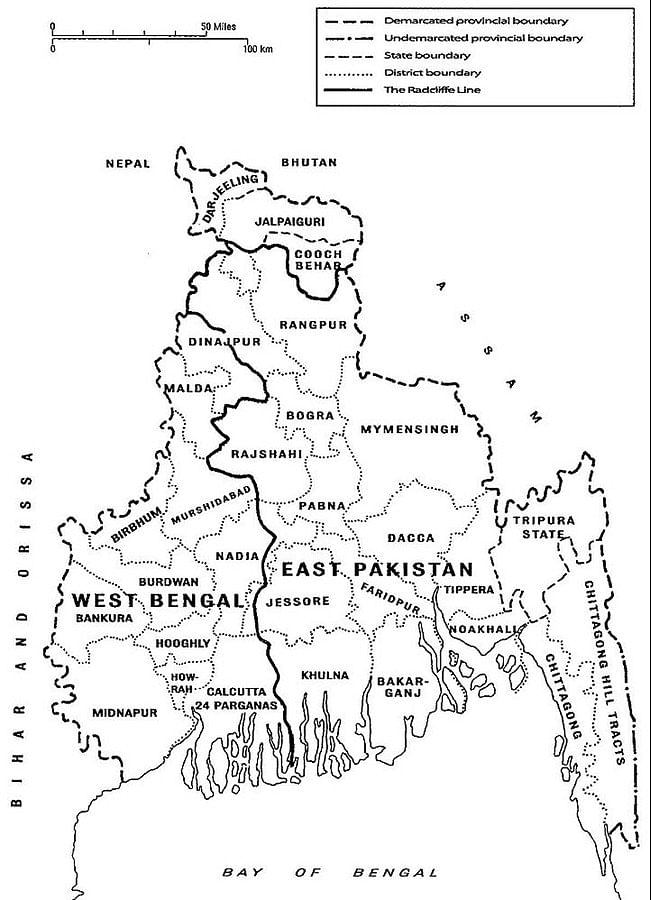

The Partition in 1947 was the result of a complicated series of historical forces, circumstances, aspirations and machinations that played out over vast stretches of land and in the lives of people: millions lost their lives while many others forsook their homes in the months following independence from colonial rule. The division was the result of decisions to accept Partition as the only solution to internecine fratricide and bloodshed that had raged for many months in the cities and the hinterlands of British India. The years leading up to 1947 were eventful to say the least: the irreparable wreckages of the World War and the Great Famine of 1943, the communal riots in Noakhali, Bihar, Calcutta and Punjab, the massive anti-colonial and Left-led peasant movements were some of the churnings that the country faced, particularly in undivided Bengal. The birth of the new nation states of India and Pakistan, the assassination of Gandhi in 1948, the rioting and communal conflagrations have all lead these years to be termed as the 'best and the worst of times, occurring in crowded sequence, churning up catastrophe and exhilaration in equal measure and ruthlessly compressing vast, unprecedented, indeed unimaginable changes in the urban landscape and demography within a span of little more than ten years.'

The Partition resulted in a division not only of the geographical spaces but also of the shared history, culture, languages and memories between different communities. The nationalist historical accounts of this separation, including Nehru's famous 'tryst with destiny' speech, often do not take into account that the long-cherished freedom came accompanied by murder, mayhem, rape and homelessness for countless men, women and children. On the other hand, Saadat Hasan Manto, Akhtaruzzamun Elias and Ritwik Ghatak thought that the freedom we had gained in 1947 had come at a terrible price because it was tainted with so much violence. Was that why Partition remained a forbidden area of historical investigation for so long, and why we, as a society, chose to remain silent about it?

When Pakistan came into being, a large section of the people in East Bengal, then called East Pakistan, celebrated the birth of a new nation that was seen as a just aspiration for the marginalized Muslim communities who had for years smarted under upper caste Hindu economic and social domination in the eastern part of Bengal. However, many others felt the pain as more and more of their neighbours left for India, leaving aside homes and hearths, under a perception of violence. On both sides of the border, there was a feeling of insecurity, anxiety and a sense of loss that underlay the experiences of independence. Abdullah Abu Syed, remembering 14 August 1947, recollected:

Even now, when I look back at 14 August 1947 I think that as we, the Muslims of Pakistan, were celebrating the Independence with the joyous abandon, at that very moment our neighbouring Hindu houses, behind their gaping front doors, were hiding a group of despairing, helpless and sad people standing speechless with the thought of an uncertain future. The same had happened in the lives of almost all the saddened and voiceless Muslim families across India.

Ashis Nandy once wrote perceptively about what has remained unacknowledged about 1947: 'Like a disowned self, dogging the steps of a patient who cannot yet own up his or her illness, the past traumata of a collectivity, too, haunt not only the direct victims and the perpetrators, but also the following generations, which inherit without as much as an exchange of a word on the subject, the fears, anxieties, tensions, often even the homicidal fantasies, a genocide throws up. Unlike an unexamined life, which we are told is not worth living, an unexamined past has to be lived out over the succeeding generations.' The oppressive nationalist discourses and the various forms of political violence that have been bequeathed to the subcontinent through Partition's legacy is here to stay and it is only after decades of silence and amnesia that the human cost of 1947 is now painfully coming to light. One can then say that the Partition of India is a longue durée rather than an event, a barely perceptible shadow that has stretched its tentacles over and into our present lives. For example, Bangladesh's birth in 1971 subverted in some ways the legacy of 1947. When the British left India in 1947, the two nations of India and Pakistan came into being to accommodate Hindu and Muslim nationalist interests and goals. Carved out of British India, Pakistan, comprising of two halves of West and East Pakistan, was an anomaly in geographical terms. The two parts formed non-contiguous segments of one nation separated by almost thousand miles of Indian territories. The difference in languages between the two halves would result in a popular outpouring of resistance in East Pakistan and Bangladesh came into being on the basis of her linguistic and secular identities. So, in one way, 1947 gave rise to other political upheavals that reconfigured the previous divisions and gave rise to other forms of political processes.

In Partition Studies, a new thrust is discernible in the last few decades; it has now begun to take literary representations more seriously than ever before. A demand for new resources for remembering and representing the Partition means that social relations, locality as well as memory that shapes our subjectivities, come under the historian's scrutiny. As a form of representation and construction, memory is deeply implicated with geography, so an engagement with a literary archive can be an important and significant way to enter the hidden and diffused narratives of the Partition. These texts then become sites of resistance and a nuanced understanding that challenge hegemonic narratives of identity, power and belonging. In these alternative voices and experiential realities, we can truly seek to find what the real bequests of 1947 have been through successive generations and to begin a process of healing that seems to elude us still.

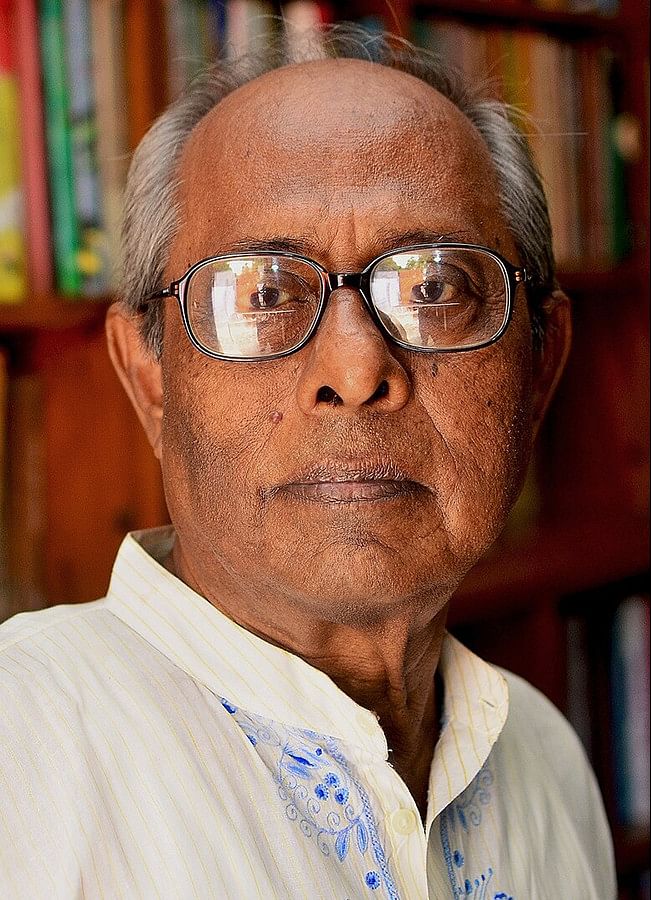

Hasan Azizul Huq's novel Agunpakhi (The Firebird, 2008) is an example of this kind of interrogation of our shared past. The narrative can be seen as an enquiry into the meaning of home, belonging and habitus, a departure of sorts from mainstream Bangla partition fiction because it attempts an altogether different aesthetic exploration of language and form through a subjectivity that is doubly marginalized. Written in a dialect spoken in areas of southern Bengal (where Huq had spent his early years), it is a narrative that foregrounds minority (in terms of gender, language and religion) subjectivity, and brings out the less visible and delayed effects of displacement and violence within the family and in community spaces. A first person account by a Muslim woman of her life in a village in undivided Bengal, the novel narrates how the village (and the self) changes through the events of war, famine and the division of the country. The phenomenological time of the narrator's adolescence and adulthood (seen as a duration) is destroyed by the Partition that irrevocably brings a schism in her and many other lives. It also changes the definition of her experiences of belonging to a land that now becomes alien. The occurrences of the events leading to the partition interacts and modulates other experiences of collective life: the novel explores both the synchronic and diachronic processes of history and memory. Her life, hitherto intricately connected to the land, comes under scrutiny as her family leaves for East Pakistan, the country designated for 'Muslims'. The unnamed narrator, known as Meter Bou (the second daughter-in-law) refuses to leave her home and her land where she belongs. The primacy of region over religion is part of her self-imagining: home is the village rather than the new nation. This act of transgression marks her body's relationship to space and to language: her identity as a woman, hitherto defined by her role as a wife and mother, is now moulded into another set of aspirations. Refusing territorialism as a precondition of nationalism, she sets into play new gendered notions of citizenship and subjectivity. Through Meter Bou's narratorial voice one begins to see how her identity is constructed through significant moments of personal and social history and is mediated by location and culture:

The ponds, lakes and the earthen houses with their ribs exposed told everyone that our village was ancient. The roads were paved only during the last war. Throughout the day only two cars went by over that paved road, one in the morning and another at dusk. Otherwise the day was silent: the village did not seem of this world. I know the village quite well! The large pakur tree in front of the homestead, isn't that unlucky? Pakur is a large tree (maharuha), and it should be in the middle of a field or at the centre of the village – where people gather to smoke their hubble bubble – but no - it was right in the middle of the courtyard.

In the novel, the village that the narrator describes is not just a place where she lives; it is also where one's child has died and dead spirits hover in the air. The homely and the unhomely traverse and conjoin in the soil that gives a rich harvest every season: the village is inhabited by the living as well as by the dead:

People think that there were two kinds of humans – dead and living. They must exist together. All those living people who roam inside and outside, who can tell one or two of the dead are not among them? There is no way to know.

The narrator is defined by her experiences of marriage and adulthood in a landscape that is remembered through language, a language that is both uncanny and sublime. In her remembrances, nostalgia plays a creative role and the surfeit of memory instead constitutes the 'affective' dimensions of loss of the everyday markers of lived experience. Thus, in this novel, place/space (and time) are not passive containers for historical events but a vital and living presence whose mysterious and subtle properties transform and thread through human lives. The physical topos is thus transformed through memory into the mysterious and subtle marker of a 'home'. How does the landscape confer meaning to the self? To belong to a place is not only to be embedded in its geography but also to be immersed in the linguistic, cultural and social practices that emerge in relation to the place. The narrative of this novel that unfolds in the first years of the twentieth century and ends a few years after the partition of Bengal (and India) in 1947 is both linear and meandering with its own pace. The span of time captures the changing intercommunal realtionship in the village where the Muslims are a minority. The village, a self-contained and independent site is yet marked by clear divisions of caste and religion. Yet the quotidian world of labour is a shared world of work between Muslims and Hindus although each group knows the taboos that govern their realtionships. The politics of difference that is on the rise makes Meter Bou impatient:

What is the use of thinking about the differences between Hindus and Muslims? Religions are different from each other…there are no end of differnces between Hindus and Hindus! Aren't there differences among Muslims? In this world we are all different. What is the use of thinking about it?

In the novel, the domestic world of a well-to-do Muslim household at the turn of the century is drawn in meticulous detail, but the domestic is aligned and complemented with the world outside. Although Meter Bou lives in purdah, she is aware of her thirst for the world and the changes that come slowly and inevitably upon it (pithimite elom kintuk pithimir kichui dekhlom na/I came to the world but saw nothing of the world). The Roys, a prominent Hindu Brahmin family, are on a decline. They have lived on ancestral wealth and the present generation have neither educated themselves nor have they worked for a secure future. The Hindu eclipse is in contrast to a new Muslim awakening. The narrator's husband becomes the first minority President of the district Union Board and buys the Roy's land at an auction. As the century unfolds its turbulent history, Meter Bou tries to understand what each of the events presage for her family and the small village community. The isolation of the village is broken by the World War when white soldiers come to live in a camp nearby. The war and the subsequent famine destroys the insurmountable difference between the city and the country: the skyrocketing prices, the 'gora' soldiers, guns and cannons bring the two spaces in interlocking relationship with each other. The pre-partition riots also show how the differences have merged: the riots in the city soon spread to the village communities as well. Yet they bring out new questions about identity that have never seemed so important before:

Human beings have lived their lives, with their children, their homesteads; everyone to their own lives…who was a Hindu and who was a Muslim?...I don't want to think of it even now but from time to time the thoughts came to my mind: what if the riots started here too? Maybe the husband of Napit Bou or Hola Bagdi's father will come to kill my two sons? Impossible!

When she hears that her Muslims neighbours are demanding a separate nation, it is equally impossible for her to grasp the concept and reality of Pakistan. Her gendered undertsanding of the call for separation is ultimately a sharp ctitique of the politics of aggrandizement and self serving nationality, as she challenges the structures of habitus by contesting the dominant communal view. Her memories come in the way of a new history of cruelty and separation that she rejects:

Shame! Has everyone forgotten everything? One field, one riverbank, one road, one drought, one monsoon and one harvest that we all share – Alas for a few men on both sides, everything is spoilt!

Meter Bou's realization that 'when it is morning and there is light, I will face the East. I will look at the rising sun and I will stand up again' is a language of agency and self-reliance. Taken at a symbolic level, the East would mean the birth of Bangladesh, whose flag holds a rising sun and whose coming into being will challenge the 1947 Partition that had taken place on the basis of religious nationalism. Huq's novel then gives us an unique way to understand 1947: how the vagaries and exigencies of division and cruelty keep churning to give rise to another history and other possibilities of hope and recovery.

All translations from Agunpakhi are mine

Debjani Sengupta teaches at IP College for Women, University of Delhi

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments