Making a killing out of a killing

A visit to any bookshop today will attest to the reading public's fascination with crime (and criminals). While the appeal of a good murder mystery has long been established by the likes of Agatha Christie, it is the increasingly violent crime stories of today—and particularly the popularity of serial killers—that is a newer phenomenon.

I would often tease my father, who was the gentlest soul you could ever hope to meet, about the rows of crime novels—from his beloved Scandinavian noir to the more classic Inspector Maigret books—that lined his shelves. I could never get into them myself.

But what he and I did share was a degree of incomprehension about the preponderance of true crime in the bestseller lists today, because, quite apart from the gruesome nature of many cases, it is the suffering of real victims that is put on display. And however much of an outlier I may be, I can't shake the sense that it is not right to use the most traumatic experience in someone's life as entertainment fodder for others. It also raises serious moral questions when a murderer is allowed to benefit from his misdeeds by selling his story for millions. Yet we live in a world of rapacious media professionals who cash in on the preoccupations of true crime obsessives, making this an acceptable practice.

Why is that? The surviving Beatles have made it a point never to mention John Lennon's murderer by name—precisely because that is the "celebrity status" that criminals like him crave. And our fascination with the likes of Ted Bundy and Jeffrey Dahmer enables it. Meanwhile, aside from Lennon, the names of their victims are long-forgotten. Shouldn't at least some profits from the serial killer cottage industry be used to support victims and their families?

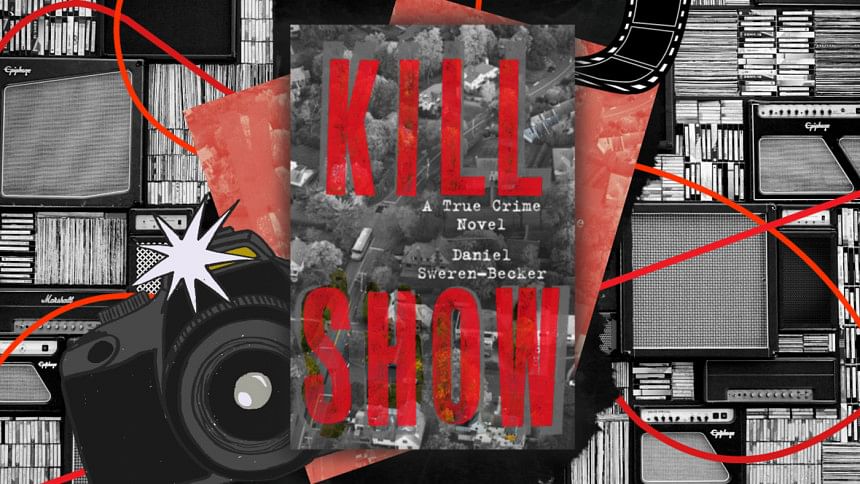

Examining some of the questionable moral aspects of true crime as enjoyment that we have all bought into is one element of the highly entertaining novel Kill Show by Daniel Sweren-Becker. When teenager Sara Parcell suddenly vanishes on a fine spring morning in Maryland, her family is understandably desperate to know what has happened. What is less easily understood is how quickly the entire nation becomes obsessed with the case. But then, cynical as it may seem, Sara is a young, pretty, white girl—and in America, that places her in the ideal demographic to receive attention for disappearing.

Amidst the media feeding frenzy, an opportunity to cash in (as it turns out, for all concerned) materialises in the form of a true crime, real-time TV show titled Searching for Sara. This is the brainchild of ambitious producer Casey Hawthorne, who manages to get her audacious idea green-lighted by the network. Meanwhile, the family's desperation for answers leads them to agree, somewhat unwisely, to take part in a show where their emotions are put under the microscope, and the investigation is filmed as it is ongoing, ostensibly to improve the chances of finding Sara alive.

In the course of filming, new angles begin to emerge, casting suspicion on various characters. And there are plenty of suspects to choose from in this ensemble cast, so we inevitably start questioning who knows what about Sara's disappearance. The TV show does in fact provide some answers as to Sara's fate.

Just not the ones anyone expected.

To add a meta aspect to Sweren-Becker's novel, a documentary is now underway to mark the 10th anniversary of the show that made television history, and had a ripple effect on the lives of everyone involved—Sara's family members, who were damaged for life; the producer and cameraman, whose careers were made; the weird neighbour, whose reputation was destroyed by lies; the detective, whose lapses in judgement got him taken off the case; and the residents of the town, whose taste of "fame" did not always bring out the best side of their personalities. Because that is the author's point with Kill Show, that nobody is really innocent in these situations—not the media networks choosing to profit off people's despair, not the "close friends" and family members who want their faces on camera and their wallets fattened in exchange for their so-called insights into the case; and certainly not the gawking misery tourists (aka travelling true crime aficionados) who want to participate in the story in any way they can.

The filming itself—like the very presence of an anthropologist studying a remote tribe—has an unforeseen effect on the outcome. And in the process, we also learn the meaning behind the ominous title of this book.

The writing style utilises the device of a documentary script, which may not appeal to everyone. But without the distracting descriptive elements that are part of any standard novel, the story moves much faster, making the book a gripping read. There is a killer twist in this novel (pun intended), and even reading it as a writer myself—and one who is always second-guessing what might happen next—I did not see that coming.

While the idea of illuminating a criminal case through a TV show/podcast/documentary is not a novel idea per se, the significance of this book lies in the fact that it holds up a mirror to our often unhealthy interest in true crime, as well as the insidious nature of media influences in our lives. If you are looking for compelling entertainment that will also make you think, this story is worth your time.

Farah Ghuznavi is a writer, translator and development worker. Her work has been published in 11 countries across Asia, Africa, Europe and the USA. Writer in Residence with Commonwealth Writers, she published a short story collection titled Fragments of Riversong (Daily Star Books, 2013), and edited the Lifelines anthology (Zubaan Books, 2012). She is currently working on her new short story collection and is on Instagram @farahghuznavi.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments