My London: An Immigrant Story

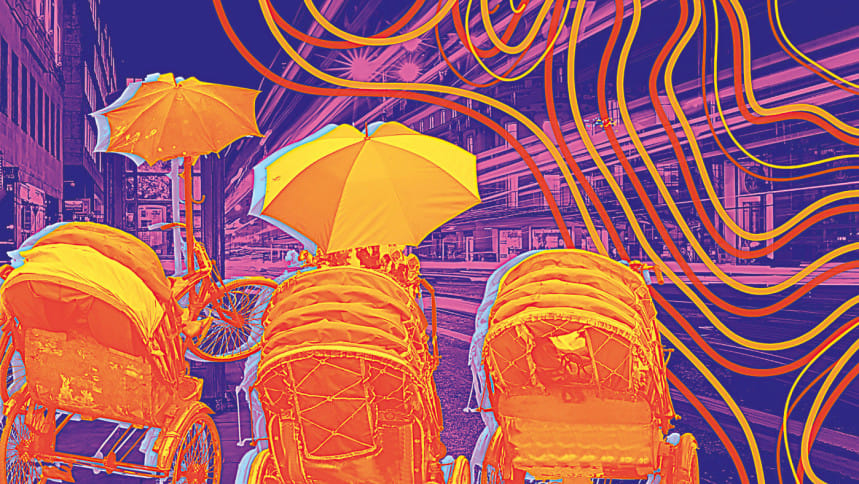

You Are a Rickshawallah

1

After three weeks of futile job-searching, you think out of the box. You have seen rickshaws or pedicabs plying the central London streets targeting tourists. A thought strikes you when you spot one or two Bangladeshi students in that line of work.

Your rent will be due in two weeks and you have no money left whatsoever. You are desperate to do anything—take the oddest of the odd jobs.

One day, early in October, you borrow £70 from your roommate and come to a parking space of a building in Warrant Street at a given time. A Turkish man there, thin and stubbly bearded, owns 15 rickshaws. You hand him a copy of your passport and the weekly rent of £60 in advance, and he hands you the key to a chain lock.

The first day you don't earn anything. Nothing on the second day either. What you can't do is talk. Other rickshawallahs are experts at smiling and greeting passersby. Plus, you still don't know all the streets. You get around China Town, Covent Garden and Soho. You buy a map.

The following afternoon, you shake the Bengali vanity off your body like a dog shaking off after a bath. And you set for a toilsome London life. A degree from Dhaka University, a profession in journalism, a decent life in Bangladesh is nothing but a memory now.

The moment you sit on the driver's seat, you want to hide your face. You dread that soon many of your fellow Bangladeshi acquaintances will recognise you, remember you, and that they will spread this around. Beyond the borders of Britain their words will reach the ears of your folks in Bangladesh. You will be forever tagged as a rickshawallah, a slur back in Bangladesh.

You are on Oxford Street when you hear a taunting comment from a pedestrian in Bangla: "Kemon lage?" How does it feel, eh? You shoot the man on the walkway a hard look and ache to spit out: "You bastard!"

2

The first day you don't earn anything. Nothing on the second day either. What you can't do is talk. Other rickshawallahs are experts at smiling and greeting passersby. Plus, you still don't know all the streets. You get around China Town, Covent Garden and Soho. You buy a map. Some drivers use newly arrived iPhones to navigate. That is beyond the ambit in your current situation. The problem with using the physical map is, it doesn't tell you which streets are one-way, and which are not.

You pedal around to familiarise yourself with the streets. Once, you come out the wrong way on the main road to Oxford St. and your rickshaw runs into a police car. The officer yells at you: "What the fuck are you doing?" You panic. "I'm so sorry, so sorry, so sorry", you say, "it's my first day." (It is your second day actually). You turn your rickshaw straightaway and move toward the flow of the traffic.

The third day, you hit some luck. It is a wet day and it starts raining a little. You are near Selfridges when a mother and her daughter approach you. Would you drop them off at Marble Arch? "Sure, please hop in", you say. It is not easy pedalling two passengers toward Hyde Park, because that is up the hill. You are panting while pedalling. The rickshaw moves at a super slow speed. One can rather walk faster there. You worry that you won't make it.

Exhausted and drenched in rain, you reach the destination. They pay you a 20-pound note where the face of Queen Elizabeth is ablaze with a smile. The mother is generous with the fare. You haven't fixed the price. You would have been okay with a tenner. Perhaps your exposed sign of overexertion and soaked clothes made her sympathetic to you.

Should I head home now? you think. You decide to stay a little longer. Like Bangladesh, you figure, rain is good for rickshawallahs—an opportunity to earn extra. In Covent Garden you make £5 from another short ride. That is all. Though you stay until 11 at night, you get no other passengers.

Having taken the rickshaw to the garage, you are waiting at the bus stop to catch a bus home. You are shivering in the cold since you are wet. A middle-aged woman next to you is smoking. "Would you like a cigarette?" she asks. You look at her kind eyes and say yes. She gives you a cigarette and a lighter.

3

That night, when you get home after midnight, you are hungry like a street dog. In the kitchen you find out that no curry is left for you in the pan. There is rice. But how will you eat it without curry? In total, there are eight souls in this three-bedroom flat. You all share grocery expenses, clean the flat and cook in rotation. They shouldn't have eaten your portion of curry. You fry an egg to appease your ranting stomach for the long night.

Lying in bed, you gaze at the solitary window facing the street. You regret coming to London. In Dhaka, you had a writing job. You wrote about theatres, plays, jatra. London life has turned you into a rickshawallah. What a promotion!

You buy a raincoat the following day. That day you pick up three young men from the British Museum and drive them to Leicester Square. The fare is fixed at £20. It is a heavy load. You are sweating like a pig and breathing like a sick old heart. The moment you arrive at the destination, and before you dismount the saddle, the three guys run off in front of your eyes in two directions. You are dumbstruck. All you could utter is: Hey, hey, hey! Chasing them is pointless. You cannot outspeed them with a rickshaw. And you cannot leave the rickshaw behind to chase them.

Looking vacantly toward the road of their disappearance, you feel like crying.

That day you earn nothing.

You are still learning every day, mainly memorising roads and directions. You bike around Soho, Covent Garden, Shaftesbury Avenue, China Town, Palace Theatre, Prince Edward Theatre, among other places. By the end of that week, you pocket only £90. After paying the weekly rent you just save £30.

It is frustrating. Would I be in luck in this business? you wonder. Am I fit for this profession at all? But what else could you do? It is at least something rather than doing nothing. You speak to your fellow rickshaw drivers. They say you will make it in due course. There is a kind of thrill in this work. Once you discover it, they remark, you won't leave this profession.

You doubt it.

They tell you they earn between £200 and £300 a week. One of the Bangladeshi boys unveils some ways to earn extra money—how to get commission from strip bars, massage parlours, model walk-ups and some hotels. The amount from strip bars ranges £5 to £10. There is one hotel off Oxford St. that pays up to £30 for bringing in a client.

All you have to do is get your passengers there, wait for them to check in, and you will receive your commission straightaway. You see possibilities to survive in this profession. You take the names of two strip bars in Soho and the hotel on Oxford St., realising why most drivers carry a plethora of hotel and massage parlour brochures with them.

Rahad Abir is the author of the novel Bengal Hound. He has an MFA in fiction from Boston University. Star Literature is currently publishing select sections from his novella My London: An Immigrant Story. Its first chapter was originally published in Witness magazine.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments