Why the delay in declaring minimum wage for RMG workers?

The tenure of the wage board formed to recommend the minimum wage for ready-made garment (RMG) workers expired on October 9, but, disappointingly, they are yet to come up with a proposal for a much-anticipated wage hike. At their third meeting on October 1, the wage board members said they would visit RMG factories across Bangladesh and submit proposals based on their findings, possibly in the third week of the month. A new wage is apparently likely in mid-November.

Amid the worst cost-of-living crisis in over a decade, which is ravaging the life of everyone but the superrich, such delays are no doubt unwelcome by the workers, a majority of whom are living from hand to mouth, racking up huge amounts of debt which they cannot afford to repay with their existing salaries. The urgency is clearly lost on the wage board members, who could only manage to meet three times over the past six months, and, by their own admission, are yet to even visit factories and meet with the workers. Such a lacklustre attitude – at such a volatile and crucial time, with the elections fast approaching – does not beget confidence in the wage board.

As prices of essentials have doubled, tripled and in some cases quadrupled out of reach of even the middle class, the working class has had no option but to cut back on their nutritional needs – and then cut back some more. Most have given up on chicken, beef and big fish for a while, but when eggs cost Tk 12-14 apiece, onions Tk 75 per kg and potatoes Tk 45, how much more can they even cut down? As I struggle to come to terms with my ever-escalating grocery costs, I can't fathom how garment workers are making do with the meagre amount that is left for food after paying house rent, bills and other necessities. At every home I visited last month, the story was much the same. The debts are piling up in the neighbourhood grocery shops, and much-needed treatment has been put on hold till "better times" arrive. Women's health, as always, has been the worst-affected, as the opportunity cost of an ultrasound is two weeks' worth of food on the table for their kids. Most are surviving by working an insane amount of hours day in and day out – it is now legal to work up to 12 hours a day, thanks to a circular by the labour ministry – at a great cost to their mental and physical health, on top of taking on additional manual work on their so-called weekend to earn some extra bucks.

It is a tried and tested strategy of the government to denote any mobilisation in the RMG sector as "sabotage" or "anti-state" and to conflate the sector's interests with national interests. But it would be short-sighted – and dangerous – for the government to do so this time around. Anger is slowly but surely building up among the working class, and with the elections around the corner, the government can only push them so far before they realise the workers have nothing left to lose.

Will the wage board and our policymakers truly hear the stories of backbreaking work and heartbreaking debt of the garment workers, who have kept the economy going even at its worst phases? No, if the past is any indication. Garment workers' demands for justified wage increases have been met with apathy at best and violence at worst in the past. There are countless examples of workers being beaten indiscriminately by local goons, tear-gassed by law enforcement agencies, and even killed for asking for their dues, no matter which government in power. In fact, that we have a whole police unit whose responsibility is to keep workers on their toes speaks volumes about where our priority, as a nation, really lies.

Despite the inevitability of backlash, in the absence of effective trade unions in the factories or other credible mechanisms to resolve disputes, workers have had no option except to take to the streets to demand wage hikes – as they did in 2006, 2010, 2012, 2016, and 2018. The costs of such protests have only intensified over the years, as the space for any form of dissent has shrunk alarmingly in the country. In 2016, for instance, following the wage protests, at least 1,500 workers were fired and cases were filed against 38 labour leaders and activists. Workers and activists were threatened and harassed, union and NGO offices were forcibly shut down by security forces in Ashulia, Savar and Gazipur, and surveillance on prominent union offices continued for months after the protests ended, as documented by the Worker Rights Consortium and Human Rights Watch.

In 2018, the crackdown was even more severe. More than 11,000 workers were terminated from their jobs, thousands of cases were filed against named and unnamed workers, and at least 50 workers were arrested. The state and owners saw the crackdown following the wage protests as an opportunity to weed out "troublemakers," with thousands of workers who were vocal about their rights within and outside of the factories being blacklisted from the industrial belts. According to the Human Rights Watch, police resorted to violence to quell the protests, firing rubber bullets, tear gas and water cannons at them, raiding homes of garment workers, and even going so far as to shoot at residents with rubber bullets. A worker named Shuman Mia was allegedly shot and killed during this time.

Neither the 2016 nor the 2018 mass protests were coordinated by the major labour unions – they were spontaneous reactions of workers to an unjust state of affairs. This time around, trade unions have been organising programmes here and there on a limited scale, but we are yet to see a massive showdown of workers to drive home their desperation in any of the industrial belts. As the cost-of-living crisis takes an unbearable turn, one could well ask: why aren't more workers on the streets yet? They say the memories of the last two crackdowns are still fresh in their mind. In this economy, losing a job and getting blacklisted is no less scary than being picked up by law enforcement. The state has become increasingly more repressive since the last elections, with hardly any mass movements taking place over the last five years. BNP's demonstrations in different parts of the country have been met with violence, with thousands of cases filed against its activists and leaders over the past year. The stakes of taking to the streets are higher than ever before.

The political scene is already heating up, with BNP promising to wage unrest from October 28 if Awami League refuses to budge from its position. Under such volatile circumstances, what does the wage board hope to achieve by delaying the announcement to mid-November?

It is a tried and tested strategy of the government to denote any mobilisation in the RMG sector as "sabotage" or "anti-state" and to conflate the sector's interests with national interests. But it would be short-sighted – and dangerous – for the government to do so this time around. Anger is slowly but surely building up among the working class, and with the elections around the corner, the government can only push them so far before they realise the workers have nothing left to lose. The BNP, in its obsession with its one-point demand, has thus far failed to capitalise on people's frustrations with the economy, particularly the cost-of-living crisis. When, if ever, will these parties understand that they need the working class on their side?

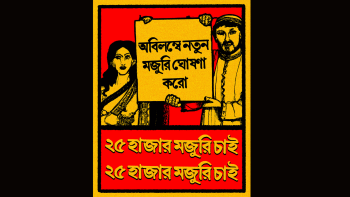

We, as a nation, have had no problems standing on the back of our workers – and breaking them if need be. We have taken their so-called resilience for granted, assuming that no matter the injustice, they can somehow sustain on poverty wages, with nothing but cheap vegetables and rice to eat, and work non-stop till their youth give out prematurely. The wage board must do the humane thing – declare Tk 25,000 as the minimum wage – instead of proposing a hike that reflects the desires of the owning class and falls frustratingly short of the workers' demands.

Sushmita S Preetha is op-ed editor at The Daily Star.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments