The underprivileged worker is not a machine

Over the past three decades, minimum wage has increased eightfold, and export earnings in local currency have surged more than 60 times. Despite this, Bangladesh struggles to compete internationally, and the blame is often placed on unproductive labour—who are hired at a base wage of $72-$75 a month. But the productivity challenges faced by the clothing industry in Bangladesh are multi-faceted and require a comprehensive understanding of the factors at play.

Ironically, industry-affiliated intellectuals and policymakers don't seem to care much about the base price for electricity and fuel, the cost of traffic jams, rent-seeking in the form of administration, and political extortion. There are high passive costs for transport, rent, expat managers hired to ensure high productivity of workers, bureaucratic bribery, lobbying, and more. The direct and indirect rent-seeking costs including out-of-pocket public health expenses of the workers are ignored too.

To note, the garment industry indiscriminately pollutes the environment, not to mention without investing in environmental treatment, and is still unable to compete internationally. Despite being the second-largest global exporter of garments, Bangladesh misses global productivity benchmarks. And this is due to policy shortcomings, not the productivity level of its workforce.

According to the Asian Productivity Organization, the hourly productivity of a Bangladeshi garment worker in terms of value stands at $3.4. In Myanmar, this rate of productivity stands at $4.1, in India it's $7.5, in the Philippines it's $8.7, in China it's over $11, and in Sri Lanka about $16.

Even with low productivity, a Bangladeshi worker working an average of 14-15 hours a day produces $1,400 or more a month. So, a wage of $140, including overtime of $30-$40, against an output of $1,400 is a bargain. What exactly is the point of complaint for owners?

With automation prevalent in many aspects of RMG production, the true issue lies in the lack of spending on training and development. The miserly factory owners often neglect investing in the skills of their predominantly underprivileged workforce, perpetuating a "helper culture" that hinders overall productivity, thus increasing headcounts. The absence of training and skill development centres underscores a critical gap in the industry's education and research landscape, contributing to a stagnant, imitative system. A holistic approach is required to unlock the true potential of this vital industry, from a more nuanced understanding of cost dynamics to investing in training and development, and from fostering a humane work environment to implementing comprehensive human resource management reforms.

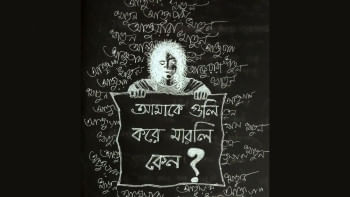

The underprivileged labourer is not a machine that will suck up productivity gains. There are no training centres to develop industrial technical skills of two million workers. Why do we expect high productivity with such a "monkey see, monkey do" system?

With the rising cost of living in the cities, workers are fleeing to the countryside, where there are jobless marches and pseudo-unemployment. But even during long periods of high inflation, there is no year-end wage adjustment. In the face of violent attacks by the law enforcement and pro-regime thugs, loss of life, bloodshed, and casualties in the wage movement, a wage rise of $35 has been proposed, totalling $100-105 monthly. But low productivity cannot be overcome unless systemically exploitative issues in the industry's human resource management are dealt with via a more humanistic wage structure, better work-life balance, allowances and benefits, and a friendly hour structure.

The prevailing practice of overburdening workers, denying leave, and providing subpar working conditions results in a lack of motivation and efficiency. A shift towards a more humane approach—encompassing fair wages, balanced work hours, transport subsidy, food and nutrition subsidy, proper child care, and improved working conditions—is essential for enhancing overall productivity.

Addressing wage disparities

In the global landscape of garment manufacturing, Bangladesh faces a considerable wage gap compared to its counterparts. While countries like China, Indonesia, Cambodia, India, and Vietnam boast average wages ranging from $170 to $303, Bangladesh lags behind with an average wage of $72-$75. Workers have advocated for a minimum wage of Tk 23,000-Tk 25,000, equivalent to $208-$227 today.

The Center for Policy Dialogue (CPD) has conducted an in-depth analysis, recommending a minimum wage of Tk 17,568 in the garment industry, translating to $150 at the official government rate, but only $140-142 at the current curb market rate. The depreciation of the taka's purchasing power prompts export-oriented industries to consider dollar-based wages, aiming to compete with countries like India or Vietnam, where the minimum wage stands at $170. The relatively lower cost of daily products in these countries, suggests a minimum wage of $160-$170 in Bangladesh.

Bangladesh is second in the world when it comes to garment manufacturing, and it wants to be the first. Yet, our RMG factory owners do not want to pay fair wages. The proposal to raise the monthly wage encounters reluctance, with a stipulation that it will remain unchanged for the next five years. This approach, however, is unsustainable in the face of rising inflation and decreasing purchasing power, making a compelling case for a minimum wage of Tk 20,000 to counter the persistent cycle of labour exploitation and discrimination. A dollar-based dynamic wage structure that is adjusted annually is essential to address the evolving economic landscape.

Furthermore, the wage crisis is exacerbated by the artificial exchange rate of the dollar, impacting the Real Effective Exchange Rate (REER) of the Bangladeshi taka. Bruegel's October report indicates a fluctuation in the REER between Tk 154.73 and Tk 173.17, suggesting that a $150 salary should equate to Tk 23,000 taka in terms of purchasing power.

A win-win proposition

The International Trade Administration's Office of Textiles and Apparel (OTEXA) reports a notable 8.55 percent increase in the unit price of readymade garments during the period from January to September 2023, rising from $3.02 to $3.27 compared to the same period in 2022.

Simultaneously, a positive shift is observed in the stance of global fashion brands towards paying higher prices for garments sourced from Bangladesh. The American Apparel and Footwear Association (AAFA), a prominent US-based global consumer organisation, has committed to cover the additional five to six percent production costs resulting from a minimum wage hike in Bangladesh.

So, an increase in production costs due to a rise in minimum wage is expected to be absorbed by these brands. Considering that labour expenses typically constitute a maximum of 10-13 percent of the total cost in the labour-intensive RMG industry, the adjustment in wages should be deemed manageable.

Moreover, the period from 2018-2023 has witnessed a notable boost in the dollar to taka exchange rate, thus adding to the income of garment industry owners. This financial upswing contradicts their claims of economic constraints that hinder wage increments.

Thus, with unit price rising, the exchange rate increasing, and the AAFA assuring compensation for a cost inflation from raising the minimum wage, the crocodile tears of Bangladesh's RMG factory owners must stop and the wage demanded by the workers must be accepted.

Faiz Ahmad Taiyeb is a Bangladeshi columnist and writer living in the Netherlands.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments