Mind the gap in centralised university admissions

The University Grants Commission (UGC) in Bangladesh recently unveiled the draft of the Central Admission Examination Authority Ordinance for the 2023-24 academic year. This ordinance is poised to revolutionise university admissions across the country, bringing all universities—including those that have historically resisted the cluster system in favour of institutional autonomy—under the umbrella of a National Testing Authority.

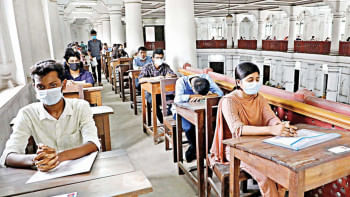

During a meeting with university vice-chancellors, acting UGC chair Muhammed Alamgir announced this groundbreaking ordinance, expressing hope that institutions would heed the chancellor's desire and align their admission policies with the proposed changes. Currently, 32 public universities conduct admission tests within three clusters: general and science and technology universities, agricultural universities, and engineering universities. The new ordinance seeks to include five major universities, namely Dhaka University, Chittagong University, Rajshahi University, Jahangirnagar University, and Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (Buet), in the centralised student enrolment mechanism for their undergraduate programmes.

The UGC chief cited the chancellor's vision probably to mitigate any resistance from the top public universities regarding a standardised testing system. Protective of their prestige of being autonomous bodies, these universities pursued independence in assessing individual applicants, believing that a centralised system might have limited predictive abilities. The Islamic University and Jagannath University also initially tried to distance themselves from the cluster examination. Some other universities adopted a different path and introduced internal oral examinations to select their own candidates. The new ordinance aims to harmonise universities on a common platform and streamline the student selection process.

In theory, the idea of a centralised university admission system is commendable. It eliminates the need for admission seekers to visit multiple campuses and pay several admission fees. Furthermore, it facilitates universities in transparently and efficiently selecting deserving candidates. However, the practical implementation of this method has revealed significant shortcomings, as exemplified by the lack of a central academic calendar for all universities.

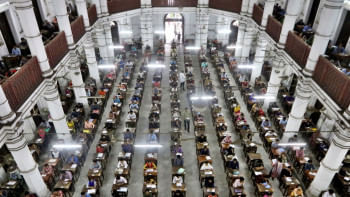

The UGC has insisted on a semester system in which you can have intakes in January and June terms. However, the Higher Secondary Certificate (HSC) examination results of 2022 were published in February 2023, and subsequently the cluster admission tests were conducted in May. By the time the admission process, including migrations, concluded on September 24, there were still 2,100 vacant seats. Many public universities failed to meet their student enrolment targets, resulting in publication of as many as seven waiting lists to fill vacant seats. This is ironic, given that more than 15 students were competing for each available seat within the public system. In the 2022-23 academic year, 303,231 students applied for 21,218 seats in the general and science and technology cluster, according to a RisingBD report.

The number of vacant seats in several universities underscores a disturbing reality: students are disinterested in certain institutions and programmes. This raises questions about whether a centralised exam can effectively achieve its purpose when universities exhibit disparities. The fact that students prefer to leave seats unfilled rather than join specific universities or programmes suggests a substantial mismatch between student aspirations and institutional offerings. This disparity is a pressing issue, given that these institutions are largely subsidised by taxpayers' contributions.

Conversely, top private universities have experienced significant growth in their fall intake. The increase in student enrolment at private universities can be seen as a consequence of the shortcomings in the public system. Many of the newer public universities lack the resources for teaching and research, making them less attractive to students. In an emerging economy, parents from the growing middle class tend to prefer sending their children to top private universities in pursuit of quality education. Those who can afford it are also seeking admission in overseas universities. The issue is multifaceted, and a centralised testing system offers a bureaucratic solution that doesn't fully address the complexity of the problem.

For a centralised admission system to be effective, participating universities must be on the same level in terms of competitiveness, prestige, and academic excellence. It's unrealistic to expect a single examination to bridge the disparities in quality and reputation among universities. While a centralised exam can help identify the most capable students, it cannot instantaneously make a subpar university more appealing.

In a country where the tertiary education system comprises students from Bangla, English and madrasa streams, addressing these issues requires a comprehensive approach. Firstly, public and private universities must align their policies and expectations within the framework of a centralised admission system to eliminate inconsistencies and reduce the burden on students. Secondly, universities should enhance the quality and relevance of their programmes to attract students genuinely interested in their offerings, all while adhering to the international standards of meritocracy.

The empty seats serve as a silent protest against the uneven growth of higher education in Bangladesh. A centralised university admission system can only be as good as the institutions it serves. If universities are not at par in terms of their academic quality, infrastructure and faculty, it is unrealistic to expect that a single entrance exam will resolve these disparities. Thus, the responsibility falls on the universities themselves to adapt and improve, with the ultimate goal of creating a system where every student, regardless of the university they attend, can pursue their chosen field of study and receive an education that equips them for the future.

Dr Shamsad Mortuza is a professor of English at Dhaka University.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments