'China, India can't replace our export market to the US, EU'

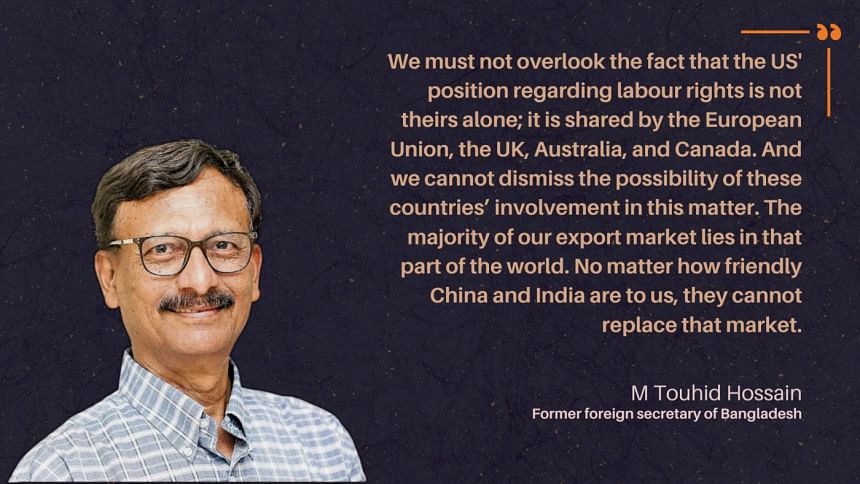

M Touhid Hossain, former foreign secretary of Bangladesh, discusses the implications and significance of the recent US labour rights policy, and the future of bilateral relations between Bangladesh and the US in an exclusive interview with Naimul Alam Alvi of The Daily Star.

On November 16, the US Secretary of State announced a Presidential Memorandum stating its intention to hold accountable those who threaten, intimidate, and attack union leaders, labour rights defenders, and labour organisations. What do you think is the significance of this announcement for Bangladesh, given the current protests by RMG sector workers?

It's important to note that the policy announcement on labour rights is not specific to Bangladesh. It's a comprehensive stance that applies to all countries. However, the United States specifically cited the case of Kalpona Akter from Bangladesh as an example of labour rights violation and government actions contradicting labour rights principles. While other labour rights activists around the world have faced similar challenges, Kalpona Akter's case was specifically highlighted. I believe this sends a message.

So, is this policy specifically for Bangladesh, and a continuation of the US' interest in our country? Or did it just happen to coincide with the ongoing minimum wage protests?

The likelihood of this being a coincidence is slim. It's not a coincidence that they used the example of a leader from Bangladesh.

You see, the relationship between Bangladesh and the US has been somewhat adversarial for quite some time now. We have either actively pursued an adversarial relationship or have been in a position where we show no concern for such conditions. Our leadership has consistently spoken negatively about the US. There is no doubt that the US is pursuing its own interests in its policies towards us. However, what the US has been saying is actually in line with what the people of Bangladesh want. They desire a free and fair election in Bangladesh. The people of Bangladesh also want this. But that didn't happen in 2014 or in 2018. And there is a possibility that it will not happen in 2024, either.

It is apparent that the Bangladesh government has deliberately taken a confrontational stance against the United States. Time will tell whether this is a wise or unwise decision. Personally, I believe that it would have been in our best interests to have a more cooperative relationship with the US, rather than taking an adversarial stance.

So, what are the options for the United States in this situation? One option would be to simply give up and say, "We can't do anything, let Bangladesh go its own way. Let India do whatever it wants in regards to Bangladesh." The other option would be to keep trying to make Bangladesh align with the US' foreign policy. And it's not at all unusual for a powerful country like the US to pose certain challenges when it tries to achieve a specific goal. I'm afraid we're headed in such a direction.

Why do we accept prices that no other country would even consider? There are allegations of internal competition. If one company declines a price, another company will accept it, cutting their margin even further. This rampant competition is at the root of the RMG sector's current challenges. We pay our garment workers half the salary of their Cambodian counterparts, and around 40 percent less than Indians. This is unacceptable.

What is the significance of this policy, especially for our RMG sector and the economy as a whole?

We must not overlook the fact that the US' position regarding labour rights is not theirs alone; it is shared by the European Union, the UK, Australia, and Canada. And we cannot dismiss the possibility of these countries' involvement in this matter. The majority of our export market lies in that part of the world. No matter how friendly China and India are to us, they cannot replace that market. Neither India nor China will offer Bangladesh the opportunity to export clothing to them overnight if we lose access to the US or the European market.

Therefore, the US doesn't need to take any political actions against us. It can inflict a significant blow to our economy with this labour rights policy if it so chooses. In some ways, it seems to me that the US has made it clear that it will take actions if necessary.

The likelihood of a positive outcome for us from a conflict with the United States is extremely low, almost non-existent. Our chances of facing significant losses are much higher. Orders from the US have already declined by three percent. Despite claims of our economy's growing resilience, many economists I have spoken to suggest that our economic foundation is quite fragile. It rests on just two industries. Textiles were our top export 30-40 years ago, and they remain our top export today. Vietnam was in a similar situation, but textiles are now its fourth-largest export. We have been unable to make that transition. If our economic foundation experiences even the slightest shock, the situation will deteriorate further. A select few individuals may prosper, but the economic condition of ordinary people is already dire. Additionally, we must make payments for our megaprojects. The financial strain will be severe by 2026. We have already fallen into a dollar crisis even though the time for these repayments is yet to come. Bangladesh's forex reserves have nearly halved.

We have witnessed improvements in working conditions in our garment factories following intense international scrutiny after the Rana Plaza tragedy. Do you believe this US policy could achieve similar results? And should we be concerned about relying on foreign powers to influence internal development?

Unfortunately, this is a pattern we have repeatedly exhibited. We only take action when prompted by external restrictions. For instance, in the shrimp industry, Western countries demanded that shrimp processing be done on tables instead of ON the ground, and that workers wear gloves and maintain a clean working environment. These were very basic requirements. Yet, our exporters failed to adhere to them until export restrictions were imposed. Such reluctance stems from our unwillingness to sacrifice even the slightest inch of profit margin.

I acknowledge that profit margins in our garment sector are not yet substantial enough to facilitate significant changes. However, we are also to blame for this situation. Why do we accept prices that no other country would even consider? There are allegations of internal competition. If one company declines a price, another company will accept it, cutting their margin even further. This rampant competition is at the root of the RMG sector's current challenges. We pay our garment workers half the salary of their Cambodian counterparts, and around 40 percent less than Indians. This is unacceptable.

Our garment sector is not in its infancy; it's a mature industry. Our factory owners should be able to negotiate with buyers in a manner that allows for fair worker compensation while maintaining market competitiveness. This is their responsibility.

However, as I mentioned earlier, it appears that a solution will not be reached without external pressure. If it is mandated that workers be granted these rights, some small businesses will probably struggle to comply. Nevertheless, I believe that a significant portion of the industry, particularly the major players, will adapt and survive.

Compared to the time of the Rana Plaza collapse, our RMG exports are now even higher. Did the industry not progress after improving the situation? Indeed, our industry can move forward by improving labour rights conditions.

Do you see this policy being a leverage or a bargaining chip in negotiations with buyers?

Given the prices at which buyers sell in their own markets, there is no fathomable reason for them to purchase at such low prices. If buyers were willing to pay slightly higher prices, significant improvements could be made in Bangladesh's garment industry. I believe that buyers will be willing to do this because they will recognise that Bangladeshi companies cannot sustain such low prices indefinitely if the labour rights condition is to be improved.

In the event of a politically motivated embargo, no other country can fully replace Bangladesh's garment production capacity. However, as it is applied for all the countries, I do not believe that Bangladesh will lose out in terms of pricing. If buyers in the West recognise that other countries cannot offer lower prices, and that Bangladeshi manufacturers will avoid internal competition and work to improve labour rights conditions, they will be compelled to agree to higher prices.

I believe that Bangladesh should raise the issue at the negotiation table. While buyers will always strive for the lowest possible prices to maximise profits, I believe that this issue will undoubtedly be addressed in negotiations, and I am optimistic that progress will be made.

So, what should be the course of action for our government now?

I emphasise the importance of engaging with the United States. Disregarding or antagonising the US will ultimately hinder our economic prospects. While India's support may be politically beneficial, it cannot fully replace the US' economic influence. We must maintain strong ties with the West to safeguard our economic interests.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments