The Continuing Relevance of Munnu

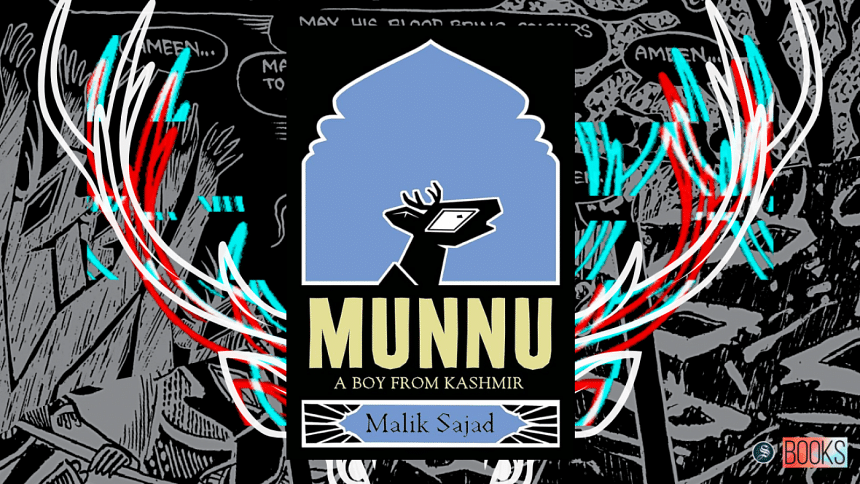

Munnu: A Boy from Kashmir (Fourth Estate, 2015) is a stark portrayal of Kashmir, not through the eyes of a foreign individual looking in from the outside, but a Kashmiri living through the Indian occupation himself. His nuanced portrayal serves as an excellent example of an oft-maligned narrative medium's capacity to display the immense range of events that have shaped a region's past and present.

The graphic novelist Malik Sajad has been influenced by the likes of Marjane Satrapi and Art Spiegelman, whose works have played some of the most significant roles in displaying the graphic novel's ability to depict dire sociopolitical conditions without any dilution of the severity, regardless of whether the story is situated in the West or in the Global South. Sajad's Munnu helps the reader become acquainted with what may be the "normal" in Kashmir, with the "normal" consisting of relatable aspects of childhood and adulthood along the searingly painful state of existence under an occupation.

The story starts from the protagonist Munnu's childhood and follows him to adulthood. Much like Spiegelman's Maus, there are characters who are anthropomorphic animals, and the protagonist Munnu is a hangul deer. However, Sajad only represents Kashmiris as animals while people of other ethnicities are drawn as humans. Those attuned to the ongoing ethnic cleansing in Gaza might remember the choice of an Israeli official to describe Palestinians as "animals". The evident dehumanisation of human beings through a comparison to animals is a well-known short-hand to demarcate a group as less than. In the case of Spiegelman's Maus, the depiction of Jews and Nazis as mice and cats respectively relies on the common idea of cats predating on mice. With Sajad, the choice becomes more perplexing as only one side is shown as animals, i.e. the Kashmiris. The choice becomes more understandable when we understand that a parallel is being drawn between the endangered hangul deer in Kashmir and the harrowing conditions in which Kashmiris exist.

One of the most unsettling aspects of the graphic novel is how Sajad incorporates the normal and simple aspects of childhood, such as taking photographs during Eid, with details of the ease with which Munnu can draw an AK-47.

It is not merely that the conflict disrupts their studies, but that it is interweaved in every facet of their life. The "normal" in Kashmir is a brutal one. However, Sajad's work does not sensationalise these events, and instead, the reader is made privy to both the happy and frightening aspects of life in Kashmir, often on the same page. The violence is an inescapable fact, never fully subsiding, yet the people try to live their lives.

We learn of the curfews and the crackdowns, fake encounters, the death of loved ones, the impact of elections, sexual assaults and violent beatings, the lack of basic necessities, and laws such as POTA (Prevention of Terrorism Act) 2002, and its effect in places like Kashmir.

The ever present danger and precarity in the graphic novel could easily feel suffocating for many readers but the author intersperses these moments with humorous incidents, even where the horrors of the occupation become startlingly clear.

While a dispassionate documentary or sensational media coverage might create distance between the viewer and the Kashmiris, whose constructed lives the former are consuming, Munnu brings a kind of piercing proximity that compels the reader to look closely at Kashmiris as whole human beings surviving in a necropolitical environment.

A tendency in the work to include multiple angles in the protagonist's personal journey extends to the parts that might be considered retellings of historical events or political critique. Torsa Ghosal's statement that the "narrative feels unfinished and unfinished it is for a reason" is an astute statement capturing one of the prime strengths in Sajad's work, which is his refusal to indulge in binaristic portrayals of groups or individuals, whether political or ordinary, powerful or endangered. At one point in the work, we come across the many comments Munnu hears from people in multiple different professions, from the musician to the ex-militant and the satirist, to the historian.

Sajad provides the reader with a collage of the different types of discourses that abound when it comes to Kashmir, all of which contain flaws, biases, and have tendencies of one-sidedness. It is as if their statements all hold shreds of truth, yet the situation in Kashmir is not told or seen in its entirety. Thus, in Sajad's telling of the story, every individual or group responsible for the present plight of people in Kashmir is shown without clear indication of who Sajad, as the author of the work, agrees with. This very choice itself might be significant, for his decision to not favour one side, narrative, or argument might point to a belief that when it comes to Kashmir, the fault for the suffering of the Kashmiris falls on everyone.

The narrative medium chosen by Sajad to tell the story, that of the graphic novel, should also be taken into account. W.J.T. Mitchell's idea of comics is that it is a "transmedium", hence it has the ability to start "mutating before our eyes into unexpected new forms". This statement is apt for describing life under brutal occupations where salvaged moments of peace can erupt into violence and turmoil within a second's notice. In a way, it helps tell the story of Kashmir as many Kashmiris experience it. The chosen medium offers a proximity and immediacy even to the unfamiliar, for it plunges a reader into minute detailed panels dispersed with hundreds of thoughts, feelings, and images that the artist is likely thinking of when portraying the characters.

In the work, we see a multitude of different types of storytelling, such as a mention of historical events in a digestible manner, a portrayal of a family's life, a kunstlerroman, myths, and others. Starting to publish cartoons from the young age of fourteen, Malik Sajad's concerns with accurate representation is clearly evident in the text. One instance of this is shown in the text where Munnu is against the use of the word intifada to describe the situation in Kashmir. While comparisons with other geopolitical issues may often help to make a situation more comprehensible to the global public, an acknowledgement of the differences in situations is crucial for an accurate portrayal of life in Kashmir. Viewing it as merely an "Islamic rebellion" or "Islamic intifada" fails to reveal the varied positions that coexist. We have to ask: Who is benefitted by such an essentialism in the discourse regarding Kashmir? By equating Kashmir with other conflicts labelled "Islamic", legitimacy is attained for the Islamophobic agendas of the fascist regimes in the current world.

Moreover, even the critiques of different kinds of storytelling exist in the graphic novel, such as that moment where Munnu is working as a photojournalist and his friend is questioning a grieving mother. The very act of questioning people is questioned by Sajad who highlights that such an action might bring forth more pain in the lives of those being interviewed as they may have to relive painful events before they have processed the loss.

Munnu is not a tragic story of a family meant to garner the sympathy of a foreign audience, nor is it a political commentary on a complex geopolitical crisis meant for discussions inside academia. Kashmir's problem is not a single issue matter, but rather a complex multifaceted one with deeply intertwined issues spanning generations.

It is a deeply personal semi-autobiographical account written from the perspective of someone whose life has been shaped by the conflict while also being in many ways, the story of Kashmir. Thus, Sajad's storytelling in Munnu: A Boy from Kashmir serves to not just provide a holistic image of Kashmir to people outside Kashmir, but does justice to Kashmiris who are often deprived of even the opportunity to tell their own stories for themselves.

Hegemonic narratives of Kashmir often rely on the common point of discussion of the crisis as a matter of a conflict between India and Pakistan. The depiction of Kashmiris is often flattened to resemble either oppressed populations in other geopolitical conflicts or groups designated as dangerous, such as terrorists. Malik Sajad's work moves away from binary depictions of Kashmir as either a blissful and beautiful place or a place marred by terrorist attacks. The fault is not placed on a single entity, and the sympathetic portrayal of Kashmiris does not lead to a valorisation or sanctification of the group. One of the most harrowing incidents in the texts involve not only the brutality on Kashmiris by occupation forces, but the brutality some Kashmiris inflict on each other. From a Kashmiri handing over his own friend to the police to a Kashmiri stealing sweets from the grave of a martyr, Sajad does not shy away from showing that Kashmiris are not a monolith, nor are they perfect victims. Yet, to many readers, this will not prevent sympathy from forming, for it shows that the people in Kashmir are in many ways the same as people all over the world.

The necessity of humanisation has become even more necessary in the present age where 24/7 news coverage and an overabundance of violent images have desensitised us. With the abrogation of article 370 being upheld on December 11, 2023, works such as Munnu ought to be read once again, for the unfortunate fact of the matter is that despite being published almost a decade back, it continues to be a relevant and accurate portrayal of life in occupied Kashmir.

Aliza Rahman has problems keeping her work short and fully acknowledges it. Give her tips at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments