Structural killings, not road ‘accidents’

Cognitive scientist and usability engineer Don Norman, in his best-selling book The Design of Everyday Things, wrote that when an error causes an injury or death, a special committee is convened to investigate the cause and, almost without fail, the guilty parties are identified. The next step is to accuse and punish them with fines and/or imprisonment. But this doesn't fix the problem as the same error will occur over and over again. To counter this, Norman suggested that when an error happens, we should determine why it happened and then redesign the product or the procedures being followed so that the error never recurs. Even if it does, having this redesign mechanism in place will ensure the error has minimal impact.

This is why Tripod Beta—the world-renowned and widely used accident analysis methodology—rather than focusing on blaming the individual that made the error, concentrates on the logical analysis of these error-inducing systemic influences. For each accident, Tripod Beta uncovers 1) an "immediate cause" (the human action or decision that led to the accident), 2) the factors or the "preconditions" which resulted in the behaviour/decision, and 3) the "underlying causes" or systemic factors (such as policy, culture, design, leadership, and more) which created the preconditions. Implementing the remedies to improve these structural factors often takes time and resources, but does have wider implications and benefits in terms of accident prevention.

However, in Bangladesh, much emphasis is put on the behaviour of individuals during the causal analysis of accidents while the underlying structural factors are neglected. This trend is most visible when the causes behind road accidents are analysed. For example, causes which are highlighted in accident analyses include the reckless attitude of the driver, the dangerous speed of the vehicle, lack of necessary skills and licence to drive the vehicle, etc. None of this is unimportant. But do we analyse why thousands of drivers behave in the same reckless manner, how they can drive on highways without having the necessary skills and licences, and why no action is taken against them when they exceed the speed limit? These key questions are rarely raised.

Thus, no matter how much criticism is aimed towards the apparent factors behind accidents, if we keep neglecting the root causes, the occurrence of road accidents will never become less frequent. Every year thousands of people are killed due to road accidents. According to Bangladesh Jatri Kalyan Samity, at least 7,902 people were killed and 10,372 injured in 6,261 road accidents in 2023.

In the case of many road crashes, it is identified that the driver did not have a valid licence or proper training. No doubt, a driver should be held accountable for driving without a licence. But if the unlicensed driver was prevented from driving, either by the authorities or by the vehicle's owner, would it have been possible for him to cause the crash in the first place?

Bangladesh lacks institutional arrangements for training drivers. In most cases, one becomes a driver after being a helper/conductor who was personally trained by a senior driver. As a result, unlicensed drivers were found to be at the wheels of at least 10 lakh registered vehicles, according to 2022 data from the Bangladesh Road Transport Authority. Moreover, most bus owners rent out buses to drivers on a daily contract. So, to maximise income, drivers steer the buses recklessly to compete with other buses, thus causing crashes. So while the driver is responsible for the crash itself, the root cause is much deeper and implicates the vehicle owner and the government by extension.

A similar situation is observed in the case of unfit vehicles. More than five lakh registered vehicles are on Bangladesh's roads which do not have a fitness clearance. Although a lot of investment is made for the construction of roads and highways, the capacity of the regulatory authority is not even enhanced enough to ensure that the licence of drivers and the fitness of vehicles are existent and up-to-date.

According to Bangladesh Jatri Kalyan Samity, 26.2 percent of the vehicles involved in accidents in 2023 were motorcycles, 14.47 percent were battery-powered rickshaws and easybikes, and 7.19 percent were vehicles like nasimon, karimon, mahindra-tractors and lagunas. Of course, the dangerous movement of these vehicles on the highways can be blamed for these accidents. But if we do not raise the question of why the world's most expensive highways do not have separate lanes for slow-moving vehicles, and if no alternatives are provided for short distance travel, people will continue to use these risky vehicles out of necessity.

In fact, it is because of the crisis in the public transport system that motorcycles have become more popular in Bangladesh. The production and sale of motorcycles in the country have gained pace due to favourable government policy, but the capacity to enforce necessary safety measures has not been bolstered proportionately. As a result, although it ranks last in the number of motorcycle users per capita, Bangladesh has the highest death rate due to motorcycle crashes in the world. Against every 10,000 motorcycles in the country, 28.4 persons die in crashes annually. However, in Vietnam, a country where motorcycles are much more widely used than in Bangladesh, this number is only 4.1 while it is 9 in India.

According to the World Health Organization, the correct use of helmets can reduce the risk of death in a crash by more than six times. So, by ensuring the manufacturing and/or import of quality helmets in the country and enforcing their use among motorcyclists, the rate of deaths due to motorcycle crashes can be significantly reduced. In Vietnam, for example, the helmet use law, Driving Under Influence law, and lower speed limits have evidently reduced the number of motorcycle-related crash fatalities.

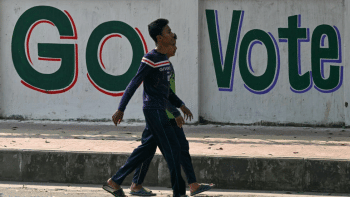

Regular deaths on the highways of Bangladesh have become quite a "normal" thing. Those who are prematurely killed on these highways become mere numbers. The dreams of a human being and the hopes and aspirations of a family are lost behind statistics. But are these tragic deaths really accidents? By definition, an "accident" is an unforeseen, unexpected, and sudden event. But when certain incidents occur again and again for similar reasons—reasons linked to the structure of the country's transport system—they can no longer be called accidents. These incidents, then, become structural killings. In this structure, the interests of the owners of unfit vehicles, unlicensed drivers, extortionist owners' associations, brokers, and government regulatory agencies are intertwined. Unless these vested groups are demolished and the structural problems are resolved, the procession of premature deaths by road crashes will not stop.

Kallol Mustafa is an engineer and writer who focuses on power, energy, environment and development economics.

Views expressed in the article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments