The heart will lead you back

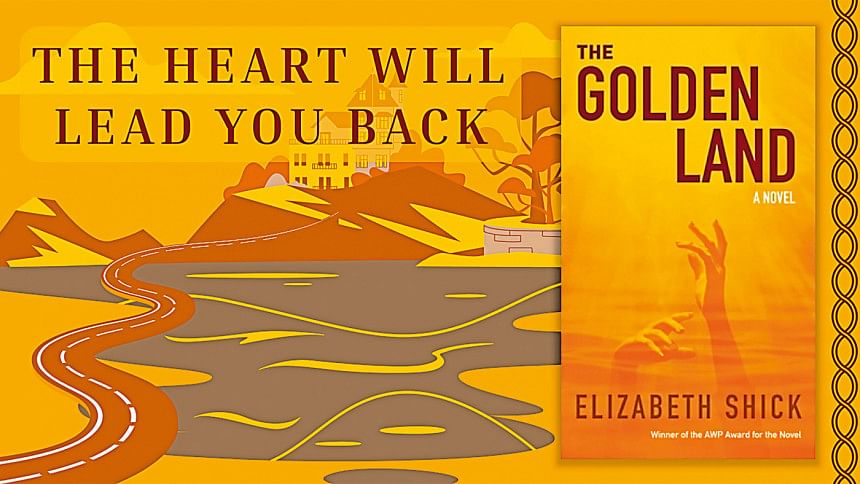

Originally from Massachusetts, international development consultant Elizabeth Shick was living with her family in Yangon, Myanmar from 2013-2019 and got to witness not just Aung San Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy win the 2015 elections by a landslide, but the military crackdown on Rakhine state that led to the Rohingya exodus into Bangladesh in 2017. Seeing firsthand the Orwellian suppression of information at play by Myanmar authorities, she felt a moral obligation to get these incredibly complex stories out there, and the result of that is her shining debut novel, The Golden Land.

We find our "outsider going in" perspective from the narrator Etta, who lets us know at the outset that she is "a quarter Burmese". Her maternal grandmother, the formidable Ahpwa, met and married an American during WWII, and moved to America. Etta's mother also married an American man. Determined to stay connected to her cultural roots, Ahpwa takes charge of teaching her granddaughters Etta and Parker the Burmese language and customs, and as an extension of this, convinces her American family to take a sabbatical and travel to Burma for a year. This trip, undertaken in Etta's childhood, has the opposite effect to what Ahpwa had intended, ending early, splintering Etta's family, and bringing her Burmese exposure to a grinding halt. Decades later, Burma is now Myanmar, Ahpwa has passed on, and when she hears that Parker is heading back to Asia with her grandmother's ashes, Etta is compelled to reopen some old wounds and follow her there.

The narrative is split into two timelines, one following the family's first trip to Burma in 1988, where Etta meets her cousin Shwe, who acts as her guide to this golden land; the second timeline covers Etta's return to Myanmar in 2011. The braiding of the dual narrative allows us to discover the events that led to the family's early departure and subsequent dissolution, as well as to underscore the effects of the military coup on the basic freedoms of the Myanmar people. Elizabeth Shick uses this fictional family, one that has a Tatmadaw General in its ranks to give us a close view of the 8888 Uprising, and the subsequent descent into a military state plagued by corruption, state surveillance, unlawful arrests, and delayed justice at every level. The Myanmar that a grown-up Etta finds is one where the basic websites are blocked, and she has to conspire with the cyber café owner to prevent her internet activity from being recorded and used against her. The adult Shwe is still as fascinating to her, if not more, and once again becomes her guide to the lives of the common people, opening her eyes to their struggles as well as their resilience in a way that would be familiar to readers here in Bangladesh.

Going into the novel, a reader of colour may be forgiven for wondering why it is Shick that gets to tell the Myanmar story, but when one takes into account the degree of censorship and the lengths to which the Tatmadaw regime will go to silence dissenting voices, one can understand why it would be harder for a native to tell the story without consequences. There are those that may recall in and around the time that the Rohingya crisis began to make headlines, news coverage of the same in our local papers added to the diplomatic tensions between our nations. The author has maintained in her notes to readers that she felt duty bound to not let these important images die.

While she turns an unflinching eye on the political evils, Shick avoids the preachy 'West is best' position throughout the story. Juxtaposing the youthful fascination of a young Etta falling in love with the beauty of the country in the 1988 timeline with the nostalgia of an older Etta rediscovering old haunts, unlocking buried memories, making new connections with a greater awareness, the author pays homage to a rich and nuanced culture with many delightful traditions. The food descriptions alone merit a warning not to read this book on an empty stomach.

Nor does she discount the legacy of colonialism that created the grounds for the military junta to take root. During one of her touristy outings, Etta meets a guide who pauses in the midst of debunking some historical propaganda to tap on a teak wall panel and say "this, this is what it was all about", alluding to the lucrative teak industry and other natural resources that the colonial powers wanted unfettered access to. All these heavy themes are delivered through a seamless blend of the personal and political, via the vehicle of memory and relationships, immersing the reader in an intimate family drama about trauma and healing, of discord and reconciliation, and through it all, a few beautiful romances.

The Golden Land received the AWP Prize for the Novel in 2021, and it was subsequently published by the University of Chicago Press. The paperback version of the book is currently available at The Bookworm Bangladesh.

Sabrina Fatma Ahmad is a writer, journalist, and the founder of Sehri Tales.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments