No more toxic ships on our shores

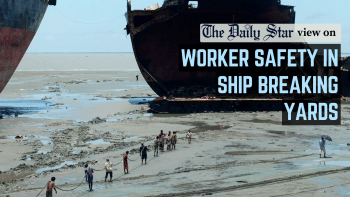

Despite countless pledges to ensure the safety and rights of workers, corporations around the world seemingly take advantage of the fact that Bangladesh is a country where regulations take a backseat. No more is this evident than in our homegrown, hazardous ship-breaking industry. Out of the 446 ships scrapped worldwide last year, 170 were wrecked on the shores of Chattogram. Of them, 159 were built before 2002, when the cancer-causing material asbestos, widely used to insulate ships, was banned. This means there are high chances that our workers, unbeknownst to them, have been exposed to this hazard.

A report in this daily highlighted that none of the dismantled ships carried a flag of the country where their company is based, which conceals the owners' identity. What's concerning is that these ships have actually arrived from some countries—including Greece and Japan—that are bound by international regulations. The tactic is as such: cash-buyers from countries like St Kitts and Nevis, Comoros and Palau purchase these ships, offering a "last voyage" package, and send the vessels to our shores for dismantling. Such coordinated evasion of binding pledges is purely sinister.

Ship-breaking is not only taking lives, but is also damaging the ecosystem as the hazardous chemicals seep into our water and soil.

Let us, however, not ignore our own shortcomings. There's a reason Bangladesh's ship-breaking industry is booming: the absence of regulations and oversight. For years, experts and activists have been voicing concerns on behalf of the workers, who regularly get injured—or even meet their demise—in the shipyards. To illustrate the crisis, since 2009, as many as 447 workers have died in these yards, and past studies have found that up to a third of the workers suffer from asbestosis, a chronic lung condition. Many have fallen to their death, in absence of any safety gear. Ship-breaking is not only taking lives, but is also damaging the ecosystem as the hazardous chemicals seep into our water and soil.

And yet, we have seen efforts of shipyard owners to reduce regulation. Last year, it was reported that Bangladesh Ship Breakers and Recyclers Association was putting pressure on the government to do away with the need to obtain environmental impact assessments. This is unacceptable. While we acknowledge that this sector heavily contributes to our economy, its current form cannot be encouraged. For this industry to be sustainable, it must follow international regulations, adhere to high safety standards, and fight the practice of international companies obscuring information about ships. We also have to analyse the sector's economic output, as the country's $6.5 billion steel re-rolling industry gets only 10 percent of its steel from ship-breaking. Above everything, we must save our workers from the disturbing reality of putting their lives on the line to make ends meet.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments