Stories of survivorship, courage, and hope for a country that cares

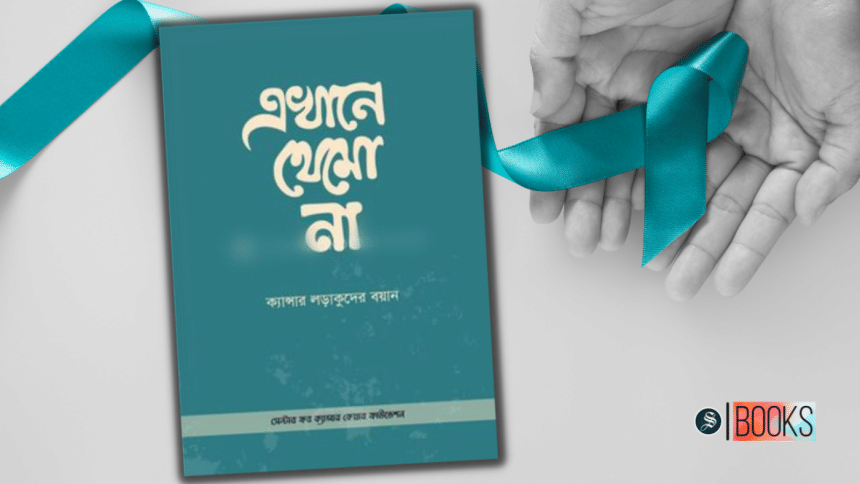

In the 1950s, "jar hoi jokkha, tar nai rokkha" was a common proverb describing tuberculosis as an imminent death sentence. But after the invention of the antibiotic Streptomycin, that was no longer the case". Although cancer continues to be similarly perceived as the call of death, these words of Dr S M Shahidullah and 41 other cancer survivors in the book Ekhane Themo Na: Cancer Lorakuder Boyan reflect otherwise—the possibility of living bold and meaningful lives even after such a feared diagnosis.

A closer look into these stories reveal reasons why cancer continues to be dreaded—it is not just fear of the malady itself, but also the challenges of undergoing treatment through an overburdened healthcare system and its exorbitant costs.

When Dr Sarwar Ali, the Chairman of BIRDEM, was diagnosed with skin cancer, he, along with his carer, had to apply for a medical visa to India for a specialised surgery which is not performed in Bangladesh. Most of these survivors (from the middle-income group and above) share similar accounts of seeking treatment abroad due to the unavailability of required care, lack of attentiveness to the patients' needs, and, at the worst of times, negligence that remains unaddressed due to lack of legal accountability.

Each year, over 300,000 Bangladeshis travel abroad for medical purposes. In India's multi-billion-dollar medical tourism industry that significantly contributes to its economy, over half of the patients are from Bangladesh. The General Secretary of the Centre for Cancer Care Foundation (CCCF), Jahan-E-Gulshan considers this outbound medical tourism to be a lost opportunity for Bangladesh. Not only did she have to overcome ovarian cancer but also a series of traumatic misdiagnosis and treatment mishaps in Dhaka before seeking treatment in India. After a full recovery, Jahan now works tirelessly to ensure others do not have to face similar hardships as herself.

The book includes the stories of several inspiring survivors who have dedicated their lives to improving cancer care in our country. Among them is the trailblazing microbiologist, Dr Senjuti Saha, who was diagnosed at the young age of 25 while pursuing her PhD in Canada. Within a year, she was able to return to her studies and is now using her second lease on life to ensure equitable access to public health services in Bangladesh. After being diagnosed with stage four cancer, the President of CCCF, Roksana Afroz, realised the significant gap in mental health support for cancer survivors. She then completed counselling training, and now provides this necessary service to others. Breast cancer fighter, Tahmina Gaffar, founded the Oporajita Society Against Cancer that raises awareness among female garment workers and schoolchildren, and establishes women's support networks across the country.

These individuals (among many others in the book) clearly show that there has never been a lack of talent capable of addressing our many challenges. But this certainly cannot be done alone and neither should it be an outcome of heroic pursuits. Health is a fundamental human right for all citizens. The State, the influential and wealthy, must strengthen the public health system that struggles to serve over 167 million people.

The urgency of the situation could not be more pronounced. In 2022, 167,256 people were diagnosed with cancer, while a staggering 116,598 succumbed to it. This rising trend is linked to exposure to environmental pollution such as contaminated air, water and adulterated food—even the beloved shutki is dried with carcinogenic substances, and the unabated use of agrochemicals and toxic industrial waste have plagued the taste of a fresh catch from our dying rivers.

Between 2015-2021, Bangladesh received more than US$ 2 billion in funding to improve its air quality, yet in 2024, the source of life for Dhaka's inhabitants ranked among the top five most polluted in the world. According to the Department of Environment, brick kilns, industrial activity, construction and vehicles are among the main causes of air pollution.

In spite of all this evidence, only a meagre 5% of the current national budget has been allocated towards the health sector, while more than double the amount funds mega construction projects. In 2019, the government approved a TK 2,388 crore project to set up specialised cancer centres across all eight divisions yet in 2022, progress remains staggeringly slow with reported allegations of mishandling of public funds. At our current trajectory, perhaps we will have more flyovers to journey to untimely death, unless we accrue catastrophic debts or are affluent enough to fly out of Terminal 3 for a chance at survival.

Drawing from lived experiences, the final chapter outlines pragmatic steps for addressing urgent gaps in cancer care, of which I will highlight three. First and foremost, regular screening and preventative care. Early detection is the most effective and least costly tool against cancer with even 95% survival in some cases. The government's ongoing Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination campaign against cervical cancer is a commendable step in that direction.

Similar initiatives are also needed to address the most common cancers affecting lungs, breasts, oesophagus and oral cavity, for which tobacco usage is a proven culprit. Article 18 of the Constitution of Bangladesh states that the State shall prevent the consumption of substances injurious to health, yet why does our State own 9% share in the British American Tobacco Bangladesh (BATB)?

Another key step is to establish a national cancer care fund, especially to support low-income groups who face dire financial hardships due to the high costs of cancer treatment.

Awareness campaigns at the community-level through culturally sensitive means must go hand in hand. Various myths that cancer is contagious and the result of past misdeeds ("paaper fol"), and cultural constraints must be openly discussed and dismantled. These particularly affect women who often neglect their health because of the "arektu dekhi mentality" ("let's wait and see"). The use of "Poter Gaan" (folk theatre) by Amader Gram is among some of the innovative culturally-grounded interventions discussing tabooed topics of women's breast health in rural public spaces. Knowledge of preventative measures can literally save lives, as it did in my own case of detecting breast cancer at an early stage.

As the cancer fighters in this book step forward to lend their support, we hope that many others will do the same to ensure that more people can live bold and meaningful lives, in a country that cares.

Ekhane Themo Na: Cancer Lorakuder Boyan is published by the Centre for Cancer Care Foundation (CCCF) and distributed by the University Press Limited (UPL). Copies can be purchased at Rokomari. To learn more and join the CCCF community, visit their Facebook page.

Adiba Afros is an independent researcher, a breast cancer survivor, and one of the contributors to this book.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments